Lyric shard as grief’s material

A review of Diana Khoi Nguyen’s ‘Ghost Of’

Ghost Of

Ghost Of

Part archive, part elegy, Diana Khoi Nguyen’s debut collection of poetry, Ghost Of, presents the haunting portrait of a grieving family set against a backdrop of intergenerational trauma. Written four years after the poet’s brother took his own life, Nguyen’s poems register this loss as it is refracted through the story of her parents’ immigration to the US as refugees in the wake of the Vietnam War. Even as she explores her own positioning within a phenomenon with global reach (the Vietnamese diaspora), Nguyen focuses her gaze on materials close at hand; she opens a family photo album and uncovers the intimate details and the cutting edges of the scraps therein. The collection, selected by Terrance Hayes as the winner of the Omnidawn Open Poetry Book Prize, combines reproductions of family photos, visual poetry that directly responds to these photographic documents, and more formally conventional lyric to produce a spare but stunning tribute to her departed sibling, and to the family he left behind.

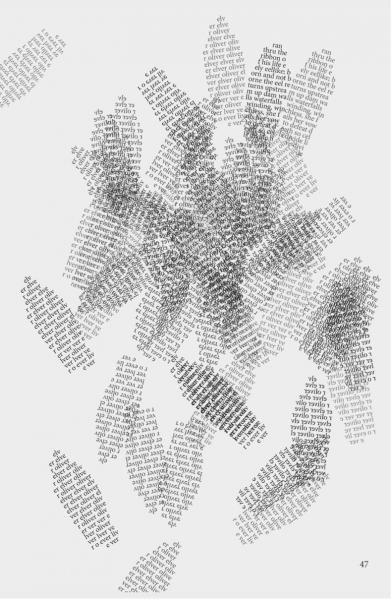

Before his death, in a symbolic act of defiant self-deletion, Nguyen’s brother cut himself out of the family photos on display in their childhood home. Nguyen returns to these same photos to examine the shape of this loss. Arguably the first “poem” of the collection is a page filled with Nguyen’s brother’s name printed again and again in a faint gray text: “oliver o o oliver elver oliver elver oliver oliver oliver ver elver.”[1] The page repeats the name desperately, the word dissolving into echolalic nonsense at moments pierced by exclamations of grief — “o o oliver.” Cut out of this gray wall of text is a two-inch-tall human figure, shadowed at its edges.

Versions of this cut figure reappear in a series of five triptychs that combine word and image. Each triptych constellates a slightly-double-exposed image (one of the family photos) that preserves Oliver’s cuts, a section of text that takes the approximate shape of the photo’s excised piece, and another section of text that recreates the broken shape of the remainder of the photo. If the second section of the triptych seems to recover a scrap that had been lost as it was destroyed by Nguyen’s brother, the third section preserves and re-presents a material remainder — the family photo that he left behind. At first, I was tempted to read the second section — the shard of text that references the excised piece of the portrait — as a replacement for the body of the speaker’s brother, but these shadowy and sonically sumptuous poems resist easy repair. Holding the book in hand, as I close the cover and bring the pages to touch, the photo and the shard of text do not align perfectly; the poems in their visuality insist on this moment of misfit. Further, the language in the second section of each triptych does not complete the wall of text in the third section, but instead forms its own poem within a poem. Try as each triptych might, it cannot remedy this wound, nor reconstitute the body that has been taken from the speaker. These triptychs serve as subdued but luminous primers in loss’s persistence, its habit of redoubling and reemerging, its echoes and its hauntings. Poetry, in Nguyen’s deft hand, becomes a place to reencounter this loss, to render its portrait, rather than a space of redemptive escape.

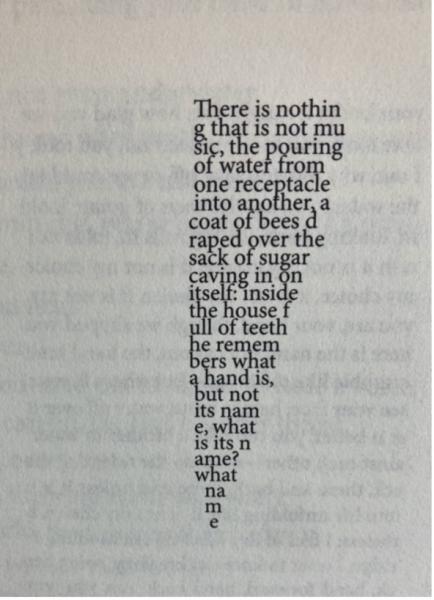

In the third triptych, the winnowing point of the shard of text in the second section instantiates a verbal pattern that Khoi employs heavily throughout the collection. The speaker repeats herself, ritualistically, mechanically, before the shape of the poem cuts the voice short:

There is nothin

g that is not mu

sic, the pouring

of water from

one receptacle

into another, a

coat of bees d

raped over the

sack of sugar

caving in on

itself: inside

the house f

ull of teeth

he remem

bers what

a hand is,

but not

its nam

e, what

is its n

ame?

what

na

m

e (43)

The slightly frenzied repetition cycles through permutations of the same word — here, “name” — each articulation a differently cut and distorted ghost of its previous articulation. The sudden ending of the repetition produces an unexpected and jarring question, “what name,” without a question mark, perhaps to indicate that the poem does not expect a response. “Oliver,” then, seems both the right and the wrong answer to this non-question. In this poem, the name is withheld, emphasizing the lost brother’s illegibility. The cutting-short of the question repeats Oliver’s cuts both physical and metaphorical, bringing to mind both his manipulation of the family photos and the premature end of his life.

If “Triptych” denies the naming of loss, in other poems in Ghost Of, Oliver’s name is repeated to the point of excess, becoming a graphic print of the person who is missing. Five poems in the collection are entitled, “Gyotaku,” alluding to the nineteenth-century Japanese practice of nature printing, where the body of a fish is inked up and then pressed into paper. The poems do not reach for bodily relics to assign to the lost brother — these are unavailable. Rather, the brother’s impression is what is preserved. Like the triptychs, these poems repurpose the shape of the photo’s excised pieces for their visual form. However, here the form produces a textual “stamp” which is then pressed all over the page (at times overlapping, and at varying saturations) to recall the repeated and increasingly faded printing of an inked fish. Some of these printed bodies simply repeat Oliver’s name; others compose their own lyrically incisive texts, but in combination the overlaid prints produce a swarming static — what is signal and what is noise? How does meaning emerge from grief’s haze?

Oliver’s haunting is multiple, contradictory, and durable. He is both unavailable and inescapable. The triptychs and the gyotakus — the two forms both ruptured portraits composed of impressions — enact visually the haunting disturbance of grief that other poems in the collection enact verbally. For instance, the poem “Grief Logic” displays a logic which is not logic, where causation and explanation are absent, but articulation persists. The speaker lists a series of “if-then” statements (“If you swim against the fish, your legs will grow longer”), which begin in a surreal register, but slowly degrade to reveal a motivating pain: “If your brother dies, you will see your brother. / If your brother killed himself, you will see your brother. / If your brother killed your brother, you were a brother. / For the brother is a subverter of the sister” (45). The poem is an oversized suit hanging off the mind’s body. The language contorts, it itches against common sense. The verse’s torsion exaggerates its inability to render the logic of suicide, and reveals how such an event inevitably resists explanation.

The title poem, “Ghost Of,” does not arrive until the third and final section of the book, at which point the figure of Oliver has become a presence in his recurring absence. In this poem, the speaker offers the most sustained glimpse into Oliver’s life before his death, but even this portrait is held at arm’s length, and when the speaker turns to look, what she finds is more penumbra than substance: “Sometimes the son feels like a shadow.” Here, again, the poem relies on the breakdown of logical sequence: “If one has no brother, then one used to have a brother” (61). The fallacy is given declarative value, but the world the speaker encounters presents itself as unchangeably senseless. And yet, sometimes these counterlogical statements produce startling and painfully lucid insights. Take, “If you have a father, then you also have a son,” which reveals a daughter’s caretaking role, the process through which children become parents to their parents, as well as the way we all become children in grief.

In an interview about the collection when it was chosen as a finalist for the National Book Award, Nguyen calls Ghost Of a “radical eulogy” addressed to her late brother — but also to her family and to “others affected by the Vietnam War.”[2] Nguyen’s parents were Vietnamese refugees who came to the US at the end of the Vietnam War, and as such her family’s dislocation was also, arguably, its founding. Calling the collection a work of “eulogy” rather than a work of “elegy” is initially surprising since so many of the poems directly address grief and mourning, rather than fashioning themselves as documents of praise or celebration. Still, the slippage between eulogy and elegy may be illustrative of the specific position of a family whose history is one of diaspora. Any document of praise for such a family must also be a document of loss, one that acknowledges displacement, pain, rupture. The family that emerges from this portrait is conflicted, bittersweet, and silencing.

The titular poem explicitly yokes together the immigration story of Nguyen’s parents to the story of her brother’s suicide: “Let me tell you a story about refugees. A mother and her dead son sit in the back seat of his car. It’s intact, in their garage, and he is buckled in; she brushes the hair behind his ear. This is the old country and this is the new country and the air in the car is the checkpoint between them” (62). The “this”-es in the passage are slippery. Which is alive — the old country or the new? In this car, the territory to be escaped and the territory of refuge become one and the same. In this scene’s staging, the immigrant mother and the departed son are both figured as refugees, even if they flee different forces. Balanced against and in tension with a narrative of American redemption, this poem, and the collection as a whole, powerfully recognizes suffering and loss in displacement, and illustrates how that loss refracts and echoes across generations. Later in the same poem, the speaker asks herself, “Is belonging and fulfillment possible without family? No. Is it possible with family? No” (63). Here the speaker acknowledges that sometimes our shared griefs and our shared sufferings are what offer us community. A portrait in tribute to this family, then, resembles the photos Oliver altered; the eulogy must be and is “radical” — its cuts tender, if not consoling.

1. Diana Khoi Nguyen, Ghost Of (Oakland, CA: Omnidawn Publishing, 2018), 11.

2. Emily Temple, “Meet National Book Award Finalist Diana Khoi Nguyen,” Literary Hub, November 5, 2018.