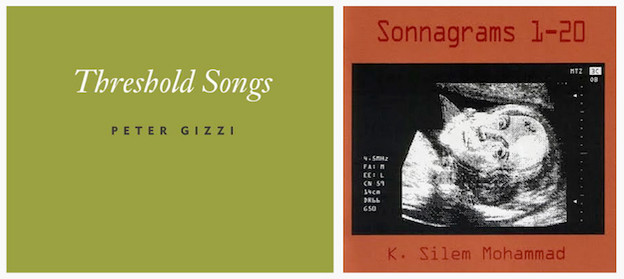

Songs and sonnets

A review of Peter Gizzi's 'Threshold Songs' and K. Silem Mohammad's 'Sonnagrams 1–20'

Threshold Songs

Threshold Songs

Sonnagrams 1–20

Sonnagrams 1–20

In their latest projects, poets Peter Gizzi and K. Silem Mohammad recycle and rework old forms, experimenting with what poetry can do in the present through engagements with the past. As they reinvent the traditional forms of sonnet and elegy, Gizzi and Mohammad put pressure on how contemporary poetry straddles poetic tradition and contemporary life. In his Sonnagrams 1–20, Mohammad uses Shakespeare’s sonnets to generate new anagram sonnets that pair Shakespeare and Flarf in a hilarious and fruitful duo. Gizzi’s new book, Threshold Songs, orbits around the form of the elegy. He investigates classical Greek and Latin ideas of mourning to speak of death as at once cosmic and personal. Ultimately, both collections speak to the confusing way that tradition shapes how we encounter the world — whether we organize our thoughts, desires, and distractions through a constraint of the past, or mourn using misheard, ancient language. These formally diverse collections reveal contemporary poets who turn backwards in order to write poetry very much of the present.

Mohammad’s Sonnagrams follow specific constraints. He rearranges the letters of Shakespeare’s sonnets to make new anagram sonnets. Any leftover letters go into the title. The first twenty Sonnagrams have been collected in a chapbook by Slack Buddha Press, and others have been published in journals including Wag’s Review and The Nation, and anthologies including Against Expression: An Anthology of Conceptual Writing. The project is ongoing, although doubtless when all 154 Sonnagrams are collected into a book, they’ll form one of the most fascinating sonnet sequences dreamed up in recent years.

While Mohammad’s turn to the sonnet isn’t that unusual (he did his doctoral work on Renaissance lyric and has cited many other contemporary poets working with the sonnet form), his sonnets certainly are. Flarf is a clear influence on the Sonnagrams, which can be described as adolescent, tacky, hilarious, confrontational, smutty, devastating, silly. Mohammad maintains Shakespeare’s meter and rhyme scheme, but like any good sonneteer, he plays with his constraints (including the added constraint of the anagram). After reading the first few Sonnagrams, it’s difficult to believe that they do what they say they do — that Mohammad has actually made formally correct sonnets using only Shakespeare’s letters. Rearrange a Sonnagram (a tempting and surprisingly time consuming task), and Shakespeare’s original appears. Mohammad describes how he composes the Sonnagrams — “I thought it was a way to use the technology of the Internet, an anagram generator, as a device to break down my text, to tenderize it, to make it ready for me to sculpt. But it left the composing up to me. It left it to me to make the decisions about measure and meter and rhyme and word choice. I would use some words that the Internet machine would throw up just because they wouldn’t occur to me otherwise, but all the syntax, all the shaping of it into a verse, was left for me.”

Although it’s difficult, at least at first, to read Sonnagrams 1–20 without hearing echoing refrains of Shakespeare, their distinctive voice and interests quickly take over. The first quatrain of the first Sonnagram, “Hot Butt Hot Butt Hot Butt Diddy,” provides a good example of what they sound like:

Erotic reptiles sing sweet airs to me

Amid synthetic England’s deathly stench;

Lo, unto every teenaged thigh they flee,

While friendly hamsters masturbate in French.

(Sonnet 1, “From fairest creatures we desire increase”)

Mohammad often namedrops his friends and creates a coterie of the contemporary poetry scene (as in Sonnet 43, which begins, “Now Kenny G. and Christian B. were sweethearts, / Till Kenny had an uncreative thought”). Or the couplet of Sonnet 21, “What sort of poem makes her have to barf? / Mm-hmm, aw yeah, that’s relevant — it’s Flarf!”

Some Sonnagrams are clearly structured around a planned conceit — as in Sonnet 10, where every line is about a different European country (along the lines of “Norwegian steamboats violate my dad”). Sonnet 40 is a catalogue of Bill Murray films, Sonnet 55 is composed entirely of band names, and Sonnet 72 is all movie titles. Others seem to emerge from the chaos of the anagram generator, popular culture, or Mohammad’s teeming brain.

The Sonnagrams are particularity effective, funny, and devastating, as they combine (and annihilate) high and low registers of language and culture. This happens in the final lines of “O Feces, My Feces”:

Old Sappho says the sight of one we love

Is fairer than a row of marching troops;

Our sponsor for the sentiment above:

The folks who brought us Everybody Poops

The meme of mage and poet we renege

When ego cannot reconnect the egg.

(Sonnet 23, “As an unperfect actor on the stage”)

Hilarious yes, but, in the rarefied space of a sonnet, placing Whitman’s Song of Myself and Sappho’s archaic lyrics alongside a children’s book about poop is, not leveling, but widening. Many of the Sonnagrams illustrate this always hilarious, often insightful, juxtaposition, as at the end of “Gee Whiz, They’ve hit the Eth Hut with the Eth Teeth (Hit That!)”:

This sonnet won’t be winning any laurels

In prosody or argument, alas:

I’m short on insight, euphony, and morals

(Free enema? No Thanks, I guess I’ll pass).

Hey you, Godot! We waited twenty days!

Oh yeah, we dug up Rutherford B. Hayes.

(Sonnet 24, “Mine eye hath played the painter and hath seeled”)

Mohammad often takes aim at his own poetic project. “The the the the the the the the the the Death (Hey Hey)” falls into the genre of sonnets about writing sonnets:

Hell yeah, this is an English sonnet, Bitch:

Three quatrains and a couplet, motherfucker.

I write that yummy shit to get me rich:

My iambs got more drive than Preston Tucker.

(Sonnet 47, “Betwixt mine eye and heart a league is took”)

Mohammad deftly spoofs on the constraints of his anagram project. He has all the letters he needs to begin a sonnet about sonnets, “Hell yeah, this is an English sonnet, Bitch.” The final line of the couplet, the line a traditional sonnet builds towards, arises out of the constraint — “My mad Shakespearean moves are ‘phat,’ or ‘def’: / They weave my pet eel Lenny — what the eff?” “What the eff” could be any reader’s response to many of the Sonnagrams. These sonnets don’t resolve themselves in their final lines. They can’t find closure, revelation, or even despair in the turn because that isn’t the point. Instead of writing sonnets in the twenty-first century, Mohammad writes the twenty-first century into the sonnet.

When Mohammad reads the Sonnagrams, he always gives them two titles. First there’s the Shakespearean title, a foregrounding that never allows the reader to stray far from Shakespeare’s English (which he echoes throughout Sonnagrams 1–20, from spoofs on Shakespeare’s rhyme words to campy uses of words like lo, hither, and thither). Then there’s the title generated from any leftover letters, which often includes, by necessity, acronyms, unusual spellings, and, when lots of one letter remain, not even words at all (as in Sonnet 14, “TTT TTTT (Or: TTTT TTT)”).

Words, and what words get used in poetry, are a constant subject of Sonnagrams 1–20, which, unlike their titles, almost never feature acronyms or nonsense words. This is why, at readings, Mohammad can make the distinction that the titles are often bullshit. Besides meter and rhyme, the Sonnagrams follow English syntax (even if the lines and sentences they construct are completely inscrutable, they’re correct). The words not included are the threatening ones:

I know a word the OED omits

Its syllables are fatal to be heard.

Whoever says it retches, dies, and shits;

I urge you not to utter such a word.

Although you feel the author’s days are through,

The author in the end erases you.

(Sonnet 13, “O! that you were your self; but love, you are”)

The sonnet “After Shakespeare” reverses the typical Sonnagram structure and puts the extra letters, not in the title, but in the couplet. The title provokes the question — if this sonnet is “After Shakespeare,” how much are (or aren’t) the other sonnets after Shakespeare? Mohammad uses recognizably Elizabethan language to make a point about what the Sonnagrams do:

Disloyal moon! thou hast betrayed the night,

In league with day, in fealty to lovers;

And so the clouds that chide thy stolen light

Made shades to hide the bliss that it discovers.

(Sonnet 37, “As a decrepit father takes delight”)

Mohammad makes a Shakespearean-sounding sonnet from the letters of Sonnet 37, “As a decrepit father takes delight / To see his active child do deeds of youth” (a clever take on Shakespeare as the poet-father, a rare instance of the Sonnagrams engaging on any level, jokey or serious, with the exact sonnets they anagrammatize). The attempt to sound Shakespearean emphasizes that the most Shakespearean-sounding Sonnagram actually has the least to do with Shakespeare. This sonnet only mimics Shakespeare’s language, and ends up sounding, by comparison, flat. But Mohammad knows this. “After Shakespeare” reveals what the Sonnagrams aren’t interested in (imitation) and how playing with Shakespeare doesn’t have to lead to it. The couplet recalls the dedication page of the original 1609 publication of the Sonnets and its still mysterious dedication to a “Mr. W.H.” Mohammad sets off his WS, WH and other enigmatic letters with suggestive punctuation. Do the brackets suggest another possible identity? Or a textual corruption? Of course not, they’re just leftovers, but Mohammad spoofs on how scholars read Shakespeare today by ending “After Shakespeare” with this sham puzzle.

There’s also the element of boredom to consider. After awhile, do the Sonnagrams get old? Will Mohammad’s clever, risqué, deflationary project be able to maintain itself for 154 sonnets? Although the Sonnagrams are certainly more novel in smaller portions (four or five at a reading, or the first twenty in the chapbook), the entire sequence accumulates significance as it develops. While the meter risks becoming repetitive when the nonsense begins to sound like just so much nonsense, this makes the moments that cut through it all the more devastating. This happens in Sonnet 55, when after a series of flippant comments and silly juxtapositions (“Do Thin Mints ruin death for Fred Astaire?”), Mohammad ends with the couplet, “Will no one but Neil Diamond wait my part? / When Snoopy goes Hawaiian … is it art?” The final question jolts the reader out of the amusing, the adolescent, and the absurd. Of course, any reader who has gotten this far isn’t likely to argue that the Sonnagrams aren’t art, but that isn’t really the point.

*

Threshold Songs, Peter Gizzi’s fifth book-length collection, is a series of mainly short lyrics that address, not the dead, but death itself. The volume begins with a dedication “for Robert, for Mother, for Mike called back.” “Called back” is inscribed on Emily Dickinson’s grave in Amherst (where Peter Gizzi teaches at the University of Massachusetts Amherst). Her gravestone reads, “Emily Dickinson Born Dec. 10, 1830 Called Back May 15, 1886.” Although Dickinson’s epitaph calls her back from life to afterlife, Gizzi’s dedication to his best friend, mother, and brother calls them back from afterlife into poetry.

Gizzi is interested in the vocal, the musical, the blur between poetry and song, and the human voice as an instrument that plays upon written words. Because of the absence of personal detail, these intensely private poems read, not as elegies for specific loved ones, but as elegies about how to elegize and what it means to mourn. They are poems of the threshold, the edge, the veil, the divide between life and death that isn’t so much a divide for Gizzi as a question.

Divided into five unnamed sections, the poems in this collection continue the work of Gizzi’s previous books (perhaps Some Values of Landscape and Weather especially). They find their register in the cosmic and the ordinary, the celestial seen in terms of the everyday. Sweeping, planetary movements are pushed right up next to everyday life, as in “Fragment” — “when you feel the planet spin, accelerate, make dust / of everything beneath your bed.” At their core, they are about “The must / at the root of it all, desire / and wanting, must know.” Gizzi uses line breaks to extend meaning and often makes multiple readings possible by omitting punctuation. “This Trip Around the Sun is Expensive” uses a musical repetition and refrain to describe a wintery ocean landscape:

what isinglass

moonlit wave

winter is

Winter surf

all time booming

all time viscous air

not black, night

winter dark blooming

surfs of winter ice

(“This Trip Around the Sun Is Expensive”)

Celestial movements often replace physical bodies, except strikingly in “A Penny for the Old Guy,” when the speaker asks, “Are we not bread-like, soft tissue, heat-seeking, and fragile?” Death, the decay of the body, omits bodies from these poems, which are more interested in the metaphysical than the physical.

In Gizzi’s own words, an analemma is the “path the sun makes over our heads in a given year,” a term he discovered while reading National Geographic as his mother was receiving chemotherapy. This rare moment of private detail doesn’t figure into the poem, where the parents are never so personalized. “Analemma” is a poem of tense, cropped lines about coming to terms, not with death, but its inevitability. Gizzi rewrites his elegies as they happen, “now that you’re gone / and I’m here or now / that you’re here and / I’m gone or now / that you’re gone and / I’m gone.” Language allows for the impossible:

now that you’re here

and also gone

I am just learning

that threshold

and changing light

a leafy-shaped blue

drifting above

an upstate New York

Mohican light

a tungsten light

boxcar lights

an oaken table-rapping

archival light

burnt over, shaking

(“Analemma”)

These song poems are interested in the slippages and shimmers between words, in misreadings and mishearings. Gizzi often finishes colloquial expressions unexpectedly — “In my father’s house I killed a cricket with an old sole” or “I am trying to untie this sentence.” In “On Prayer Rugs and a Small History of Portraiture,” he plays with like/light, piles/pyre, portrait/point/ pirouette, aught/awe, contrast/contest, away/a way, scene/skein/sight. In “Gray Sail,” “broad dazed light.” Gizzi delights in defying expectations and tripping up his reader — what Wallace Stevens celebrated as the imperfect, as “Lies in flawed words and stubborn sounds.”

Threshold Songs provides its own language to understand the slippages between words with the poems “Oversong” and “Undersong.” “Undersong” appears elsewhere as “Basement Song” and “Evensong,” all of which can be read as words for underworld or threshold. “Oversong” is itself an undersong, a list of words that aren’t synonyms (the Greek prefix syn means nameless, anonymous) because they reveal, by being placed next to one another other, that there are no synonyms in language, only a desire for the synonym. “To be dark, to darken / to obscure, shade, dim” becomes “throw a shade, throw / a shadow, to doubt.” This darkness feeds into Gizzi’s threshold:

to exit, veil, shroud

to murk, cloud, to jet

in darkness, Vesta

midnight, Hypnos

Thanatos, dead of night,

sunless, dusky, pitch

starless, swart, tenebrous

inky, Erebus, Orpheus

vestral, twilit, sooty, blae …

(“Oversong”)

The ellipsis both omits and extends. “Oversong” implies an unending catalogue. It is the poet’s toolbox of words to describe something that is never reached. “Blae,” a Middle English word for a color somewhere between blue and black, appears elsewhere in the collection as cerulean, agate blue, deep indigo, perspective blue, cobalt, raven’s wing, bluish, bluing. In Threshold Songs, Gizzi creates a lexicon for darkness.

Mohammad and Gizzi both borrow registers of language freely — Mohammad from Shakespeare’s English, Gizzi from the language and myths of the ancient Greeks. Many of Gizzi’s titles may require a quick Google search, “Hypostasis & New Year,” “Analemma,” “Pinocchio’s Gnosis” (another great undersong), “Apocrypha,” and “Eclogues.”

Orpheus, a figure of singing and mourning, crops up throughout Threshold Songs. In “Oversong,” he appears with Erebus, a figure for darkness and also a region of the underworld. In “Pinocchio’s Gnosis” (in Greek, gnosis is both an investigation and the knowledge that results from it), Gizzi invokes a Latin description of Orpheus, “Hey you, Mr. Sacer interpresque deorum, how about a good bray, a laugh track in sync with your lyre? No?” (Although Gizzi has cited this in interviews as Ovid’s epitaph for Orpheus in the Metamorphoses, it’s really Horace’s in the Ars Poetica. Perhaps Gizzi, as interested in mishearing as hearing, is playing a game with the reader.) He translates the Latin as “the sacred interpreter of god and man.” Interpretation (another word for poetry) is what’s sacred.

The threshold between the world of the living and the underworld was more permeable to the ancients, a literal gateway that the living could pass and return through. Gizzi’s elegies lament and seek to resurrect the mystery that has gone out of death, to reopen the gate to the underworld and let loose its song. He folds direct cues into his discursive lines, “Grief is an undersong.” Underworld and overworld, undersong and oversong, these are poems of the night, of blue that’s almost black, of grief in the air and wind.

Gizzi is particularly interested in prefixes and how they can unmake language, not as a negative force, but a widening one. The middle English prefix un takes center stage in “Eclogues”:

… The unhappening of day. The sudden

storm over the house, the sudden

houses revealed in cloud cover. Snow upon the land.

This land untitled so much for soldiers, untitled so far from swans.

(“Eclogues”)

In a later line, “To do the time, undo the Times for whom?” Unhappening, untitled, undo — three takes on how un changes the meaning of a word. In the opening poem, “The Growing Edge,” it is the “un gathering.” Un becomes another edge, another threshold, another way to triangulate death, life, and poetry. In the final lines of “Eclogues,” un is met with re as the cosmic meets the atomic:

atoms stirring, nesting, dying out, reforged elsewhere,

the genealogist said.

A chromosome has 26 letters, a gene just 4. One is a nation.

The other a poem.

(“Eclogues”)

There are moments in Threshold Songs that observe too opaquely. They begin to lose focus and pile up language without being particularly interesting. This doesn’t happen often, but when it does, it’s frustrating, as in the second “Lullaby” poem — “All animals like to nuzzle with their soft parts / what of it when you see the leafy conflagration in spring / a reminiscing eventual in small wistful bursts.” Although it hits some of the same notes as the previous poems, it has none of the distilled incision of Gizzi’s short lines or the unfolding mystery of his long ones. When Threshold Songs works (and it almost always works) it approaches the transcendent. When it doesn’t work, when it turns too far from the reader, it risks creating an impassable distance.

Like an orchestral score, Gizzi’s poems develop and repeat certain themes and phrases, giving to the final sections a built-up richness that pays off in poems like “A Note on the Text,” “History is Made at Night,” and the final poem, “Modern Adventures at Sea.” Near the end of the volume, Gizzi turns to the reader with a challenge:

I have always been awake

beneath glances, past

doorways, corridors.

I never see through you

but through you the joy

of all that is there anyway,

singing. The world

is rising and crashing,

a crescendo all the time.

Why not start

with the whole note?

Bring all you got,

show me that stuff.

(“History Is Made at Night”)

The penultimate poem, “Bardo,” plays with any Hellenistic expectations. “Bardo” sounds like a wiggy version of the bard, but it is also a Tibetan word for the threshold, specifically the intermediary state between one life and the next in Buddhist reincarnation. With “Bardo,” “called back” takes on another meaning. The poem ends with questions:

I come with my asymmetries,

my untutored imagination.

Heathenish,

my homespun vision

sponsored by the winter sky.

Then someone said nether,

someone whirr.

And if I say the words

will you know them?

Is there world?

Are they still calling it that?

(“Bardo”)

The short lines and alternating two and one-line stanzas bring a lyric intensity to one of the barest question of poetry — “And if I say the words / will you know them?” The reader doesn’t know who said “nether” or “whirr,” only that “netherwhirr” sounds like netherworld. The question, “Is there world?” is less important than the final line, “Are they still calling it that?” Threshold Songs wants, sometimes desperately, to know what to call things, in order to call them back.