'Say what you know'

A review of Eleanor Wilner's 'A Tourist in Hell'

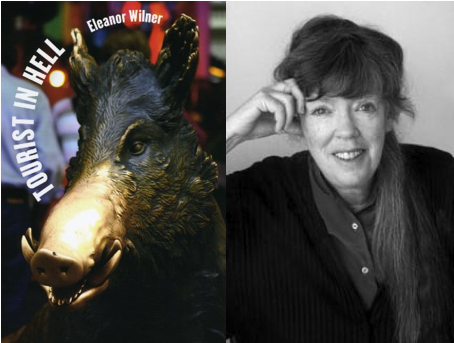

Tourist in Hell

Tourist in Hell

Eleanor Rand Wilner’s poems are adventures. These adventures include almost every subject imaginable: war, peace, nature, knitting, mountain climbing, insects and intellectuals. It is an adventure into the labyrinth of an amazing mind. Each poem starts off directly enough; soon you don’t know where the poem is going; then it leads from one surprise to another; until the whole evolves organically into one or more revelations that expand your understanding of what was broached at the beginning of the poem. She writes with the eyes of someone who just got there. But she arrives there with a depth of intelligence. For instance, the poem that begins The Girl with Bees in Her Hair prepares us as though “everything is starting up again.”

The snow is filthy now; it has been

drinking oil and soot and car exhaust

for days, and dogs have marked it

with their special blend of brilliant

yellow piss;

for a week after it fell,

the snow stood in frozen horror

at the icy chill, and hardened

on the top, and then, today, the thaw;

now everything is starting

up again —

The process of writing this review began with a reading of the several books by Wilner. Whoever has had the pleasure, indeed the privilege and emotional/intellectual satisfaction of reading Wilner’s poems will not need to be told that her work is poetry or that her poems provide remarkable surprises and insights.

In Tourist in Hell, her seventh book, Wilner examines history, current events, literature, mythology, and religion. As with the best poets, she skillfully combines autobiographical details into a larger context. About Wilner’s work, the poet Tony Hoagland has remarked, “Wilner […] has a deep and heroic belief in the transformative power of language and myth. She paddles her surfboard outside the reef where most poets stop; she rides the big waves.” Indeed, to ride the “big waves” with her is an experience that is highly exhilarating. Her poetry and each of her poems is brilliant, erudite, passionate, and amazing.

In reading through her several books, however, it is remarkable to note the consistency of her voice and the wide grasp of her subject matter throughout, from Maya to Tourist in Hell. Wilner speaks directly to the reader, whether from her own insight or through the insight of another’s voice. Or sometimes, she tells a poignant story in a way not thought of before, for example that of Iphigenia. Iphigenia, best known as the daughter Agamemnon, leader of the Greek forces at Troy, had to be sacrificed in order to appease Artemis. According to the legend, when the sacrifice is about to be made, however, Iphigenia is miraculously transported to Taurus, a city on the Black Sea, and an animal is sent to replace her (lucky for her!).

In Wilner’s poem “Iphigenia, Setting the Record Straight” (Maya) Wilner tells Iphigenia’s story with unexpected poignancy; two snippets from the poem may make my point. The first sets the stage while the final stanza brings you face-to-face with the gist of Iphigenia’s story and her bitter observation:

The towers waiting, shimmering just

beyond the edge of vision.

It was only a question

of wind, of the command of trade routes,

a narrow isthmus between two seas, possession

of the gold that men called Helen.

Iphigenia then states at the end:

I have been living, quiet, in this little village

on goats I keep for cheese and sell for wine, unknown —

the praise of me on every lip, the me

my father made up in his mind

and sacrificed for the wind.

It’s a shame to truncate this poem; however, it also highlights another aspect of Wilner’s background and interest — her knowledge and love of the classics. She is equally able to speak to the reader about her commitment to speaking truth to truth; for example, her poem “Love Uncommanded” (again in Maya):

Extraordinary, our friends

the skeptics, who are

ourselves, such an extravagance

of feints, the perfectly spun

glass, exquisite complications, saying

they know that they know nothing,

the oldest ruse, let it go.

Say what you know.

For once, be rid of the urn

with beauty chased in half-relief, the urn

with the false bottom, the ancient goad

to thirst — the right word turned

exactly on itself. Say what you know.

What more cogent advice to writers, especially poets: “Say what you know!” In Tourist in Hell,” her most recent book, the poems are more concerned with war and several of them with the Bush/Cheney administration. “Establishment” is a good example, of which only the first half of the first stanza is quoted:

Death had established himself in the Red Room,

the White House having become his natural

abode: chalk-white façade, pillars lime the bones

of extinct empires, armed men crawling its halls

or looking down, with suspicion, from its roof;

its immense luxury, thick carpets, its plush velvet chairs —

all this made Death comfortable, bony as he is, a fact

you’d barely notice, his camouflage a veil of flesh

drawn over him, its tailor so adroit, and he so elegant

But the one I like best in the Tourist in Hell collection is “Saturday Night,” a chilling poem about war and our seeming distance from it. Again, only quoted are the first introductory lines and then the last, but all in between is full of drama and … nightmare:

Moonlit rocks, sand, and a web of shadows

thrown over the world from the cottonwoods,

the manzanita, the ocotillo; it is

the hour of the tarantula, a rising

as predictable as tide; irritable as

moon drag. And if this were

an SF film, the spider would be

huge as a water tank, it would loom

red-eyed and horrible, its mandables […]

but now as the film

runs down, in a rush of stale air

the hydraulic spider deflates, the saline

leaks from the implants of the bed-

room blonde, the moon’s projection

clicks off, and the night is as it was,

a place where fear takes its many

forms, and the warships gather in

a distant gulf, where a small man

with more arms than a Hindu god,

has set a desert night alight, and grief booms;

while here, the theatres are full

of horror on the screen, and you can hear —

over the sinister canned music,

the chainsaws, and the screams —

the sound of Coke sucked up through straws,

your own jaws moving as you chew.

There is something riveting about Wilner’s poetry, and I believe it comes from her dictum to herself as to others, in the earlier cited poem “Love Uncommanded:” “Say what you know.”

Well, perhaps this review has quoted enough to give an idea of the range and depth of Wilner’s work. But I would be remiss if I left unmentioned the delightful poems in her book Otherwise that speak to issues such as “How to Get in the Best Magazines,” “Muse,” “Ambition,” and “Those who come After,” just to mention a few of what’s in store for the curious reader or for the devotee who is stirred to enjoy again Wilner’s humor as well as her experience and erudition.

One of my favorite books of hers, The Girl with the Bees in her Hair, is interesting for her playfulness with form as well as with images. Or, take for example the lines “He had made it through so many winters, / an optimist in the blizzard’s heart, staying on — “In this book she keeps introducing the reader to the next possibility, although the last poem in this book, the very fact of life’s limit comes into view:

A window

open on the sea, out there, blue wave on blue,

beyond — more blue, a chair scrapes, breaks

the spell. Words spill: So little time. So much to do.

For the reader who wants to start with an inclusive view of her work, Reserving the Spell is a compilation of her new and selected poems (over three hundred pages) taken from the several books mentioned. — That said, let the adventure begin!