Sailor, sleepwalker

A review of 'I Was There for Your Somniloquy'

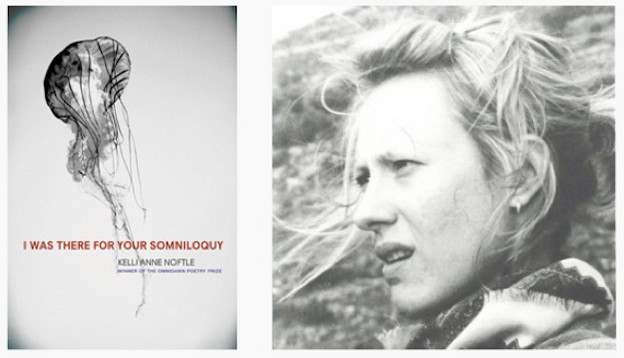

I Was There for Your Somniloquy

I Was There for Your Somniloquy

The ocean is a place of the fantastic and bizarre, a world full of creatures so different from our terrestrial designs they might as well be from another planet. Rightfully, then, the ocean is also a metaphor for the unconscious, that unseen place off the map of ourselves where the old cartographers would write “where monsters lie.” Occasionally these monsters pull down a boat or two, and sailing gently through our lives, we may come across the resultant flotsam and jetsam of some disaster below our consciousness that we can only piece together from its wreckage.

Like our globe, Kelli Anne Noftle’s book, I Was There for Your Somniloquy, is seventy percent ocean. The poems are submersibles which give us a glimpse of an alien world. It is not the cold, descriptive view of the scientist, but more the view of the visitor to an aquarium who can only see the creatures in the tanks through her own reflection in the glass.

In the first section of the book, Noftle uses the mating habits of the sea slug, tape worm, and other sea creatures as tropes to throw light upon subjects of romance and personal attraction, subjects that from a distance can seem as odd and many-legged as the strangest cephalopod. She pairs each poem with an actual scientific description of the creature; the poem precedes the description. For example, in “Penis Fencing” the note from a scientific text describes how hermaphroditic flatworms mate. Each tries to pierce each other’s skin with its penis. The loser of the battle must carry the young. Or as Noftle puts it poetically, “One of us must waste our lives caring for the sting” (18).

The scientific descriptions contain the tropes which are deftly applied to personal relationships. Some hardly need a poem to feel poetic, for example, in the poem “Mating Chain,” where this note on sea slugs is ripe for comparison:

When three or more sea slugs mate in unison, the first animal in the chain acts exclusively as female, the last as male, and the others as male/female simultaneously. (15)

The poems don’t just settle for riffing on the obvious comparison but move beyond, complicating and veering in new directions. She concludes the poem: “I twist and steer each tentacle, / tying knots against the stillness. This one to symbolize love and the other, / savagery. I’m learning the subtlety, braiding between them.” Indeed, the oddness of sea creatures is their amorphous nature, the braiding together of what we consider separate — male and female, body and limb. And the pleasure in these poems is that Noftle blurs the edges of separate subjects, showing just such a precise, strange, and creative braiding.

In the second section of the book, the speakers or subjects in the poems are sailors on the ocean of the unconscious — sleepwalkers. What we see is not what is underwater, but what has surfaced. One character pours milk into the litter box; one becomes a more tender and affectionate lover in his sleep; one (a true story) kills his wife in his sleep; and one drinks wine from a flower vase. The characters stage a play in one world when the script is in the next. The book actively muses on this bridge between the two worlds in “Ars Poetica”:

In a house I am following myself

one mirror after another

not only myself

but also in relation to. (52)

The sleepwalker is the actor of where the conscious and unconscious person touch. It is not only the conscious and unconscious, but the brain also sits at odds: “The Right Side / of the brain brims with hyperbole, the left side sits cold as a Petri dish” (51). There is disconnection, each side illuminating the other, but much is lost in the process as well, and some things happen almost without us, or as Noftle writes: “Sometimes one hand will not stop touching the other” (37).

Other poems in the collection explore the ways our actions surface from the deep through different tropes. In one series, an artist finds certain colors intruding in her paintings: “I started using white. I put it in every picture […] That’s why I started dumping all my pigments into a bucket of white” (53). The colors are thrust from the deep, as are wreckage and remains of past mistakes, which Noftle explores through the metaphor of auto accidents. In “Parts for Whole” the speaker wanders around a junkyard:

from the wreckage — that I would slip

it on, imagine she lost it before

a missed kiss, mistake, to say

an accident happened here

and what ruined skin you have, paint chipped, bruised. (44)

If the subject is the wreckage or intrusion, the act is a piecing back together. A whole picture might not emerge from this scattering, but at least “The paint thickens as you reach the center” (58).

In the end, a description only of the tropes and themes of the book doesn’t do justice to their effect. The project of the book is larger. The comparisons evoke a real and genuine sympathy. Their goal is to get dangerously close to the nature of being a divided creature. They leave one with that uncanny feeling one gets sometimes, for no reason, when sitting at a stop light or opening the refrigerator, of just how unlikely we are. And that is the real pleasure of this book, not just the shadowy subject of our motives, but how they drive us to be.