Runes in the noise menagerie

A review of Claire Marie Stancek's 'Oil Spell'

Oil Spell

Oil Spell

“[N]ight escape[s] from the menagerie / song fragment”[1] of Claire Marie Stancek’s searing second book, Oil Spell. With occultist “opening noise” and irritated lyric, Stancek warns that “darkness spreads fucks up borders between things” (8). These lines from the book’s first poem, “//|{invoke_night*[spell],” feel prophetic in the wake of recent US atrocities, where at our borders, armed immigration officers wrest toddlers from their parents, and in our schools, children kill each other while legislatures obstruct calls for gun control. The poem continues as if to foretell of leaders who use scripture to justify separating immigrant families:

impious : holding a book

and a gun the gun covered

in words the book

covered in oil (7)

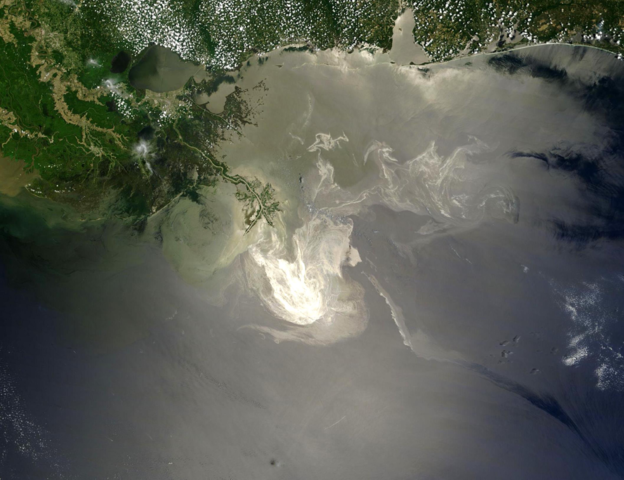

Yet these images also describe the poet’s own slippery, challenging book, which behaves as a necessarily violent force to awaken our senses. Stancek’s vision aligns her to a lineage of poetry as prophesy, one that includes writers like John Milton and Alice Notley. A noise menagerie that perplexes incongruous eighteenth- to twenty-first-century source texts, the book radicalizes Lyn Hejinian’s idea of the “open text” and Walter Benjamin’s imperative that “Every age must strive anew to wrest tradition away from the conformism that is working to overpower it.”[2] For Stancek, “conformism” refers to the linear patterning of English grammar as well as today’s most popular experimental poetics: she subverts all trends with poems that feel entirely new. Other topics include industrial and media pollution, covert drone wars, heterosexist oppression, and police brutality. Stancek montages visceral imagery related to each of these subjects throughout, implying that all such problems stem from the hierarchical social ordering inherent to the oil that fuels our industrialized minds and the greed that borders them. It’s as if she asks: what would intersectional resistance against systemic violence look like if it was sung into poems? She answers with questions in the shape of polyphonic text, but her apocalyptic poetics are not without beauty.

In Oil Spell, form becomes a revolutionary act that deforms. Stancek refuses to submit to reader expectation, ever-shifting her conceptual threads. With Lynchian cinematics, she demands we let go and experience her non sequitur dreamscapes, for “who among us is satisfied towers like dreams I / with her own designs don’t recognize” (42). In a brief interview with Omnidawn’s Rusty Morrison at the book’s release, she elaborated that some poems “came out of disturbed and fretful dreams … about birds covered in oil, about towers made of glass.” Certainly, to find logical narrative in the “masscrash” mindset that chooses to kill “8 female 05 children 07 male civilians” (40) would be to yield to the grammatical hierarchy that engenders dehumanizing social structures — structures that objectify human subjects and contaminate land with oil. Instead, the poet “masscrash[es]” multiple documents together in mercurial typography and forms that hemorrhage across the pages, creating through sonic disturbances a kind of fugal conjuration. According to the “Note” at the back, the only contextual directive offered, she has “rewritten, condensed, and scrambled” disparate sources from Anne Radcliffe, Dorothy Wordsworth, the IUCN’s Red List of Threatened Species, and a leaked Pakistani report about CIA drone strikes dating from 2006 to present. True, some might find the book too academic or resent its lack of thematic guidance (there are no epigraphs, few poem titles, and no author note of intention). But to give such context would make the book disingenuous while weakening the poet’s “fang vision spell / chirrup,” a “musical voice / falling apart” (53).

Like a fugue that opens with one musical key but is disrupted, losing itself to other utterances, the book begins with lyrical tercets that break down into pages of columnar poems: two columns face each other, recalling news articles. These open further, alternating with pages of arced text crescents that include misspelled words and cryptic messages. In these sections, language resembles curved computer code or acronymic tweets that spill across the page like pockets of oil: “chirpjugbreeerwoo-it !chirpjug after the flood slicked / stone became skin … a flesh said ERR SONG*cack-cack” (48). When considering these spills with the poems that visually recall twisted news reports, their cumulative effect suggests that we have not only forced our climate-changed environment to flood, but also that in reposting fake news, we have allowed ourselves to become “stone.” Even a birdsong’s “chirp” is reduced to “ERR.”

With further incantation, Stancek conflates eco and social justice poetry while perverting form and sonic images. Again, in the spirit of Benjamin, a dream interpretation of history tangles with our dark present. She insists we must enter that nightmare to reimagine lingual and social structures that build “THE HUGE MASSES / OF RUIN,” where we are

corroding the night

amphibians, crustaceans and beetles he trapped a bird in a

[] [] [] [] [] rot rot rot rot rot/The nest consists of silver wire basket (57)

Such text-empty brackets act as quintuple caesuras, becoming visual wire baskets that spontaneously emphasize the empty-hearted, morally rotten nature of those who thoughtlessly contaminate the natural world. Yet interestingly, that narrative is written in light grey font, implying ways that the demeaning patriarchal “he” in this account hides under the surface of things, slipping under mainstream reports that formally catalog the state of the environment but leave out significant truths. Meanwhile, in a characteristic move, Stancek compresses double spondees and harsh “r” and “c” consonance, along with static sibilance. Similarly, in a snarl of assonance and half rhyme, “rot,” “off,” and “slop” become sharp, abject noises meant to slap readers awake. Continuing with this feminist turn, we witness how he

ripped off her

PHYLLSCPS SNDS wings left her sickening

MNTN CFFCHFF in the slop” (57)

As in many other poems, vowel-less capitals chafe against each other. Here, the word “CFFCHFF” looms over “MNTN,” as if that mountain has also been cuffed by the sounds of industrial chuff and its polluting “slop.” This same poem integrates war imagery, revealing environmental injustice’s acute relation to racial violence: “overhanging grasses missile attack / mainly rocky country with cliffs and ravines, / caves, patches of woodland, scattereUSDRONEd / trees or groves” (57). The American “DRONE” here takes on several meanings, crystalizing the ecofeminist lens: the unmanned drone of war; the idle but fertile male bee; a parasite; and, a “low continuous humming sound.”[3] Indeed, the repeated short “a” in “grasses,” “attack,” “patches,” and “scattered” layers a sick, irritating drone we need to hear. Stancek’s “scattered” dirge bemoans the scabbed grassland, victim of covert US war efforts, just as in other poems, “the killed JAGGED RIDGES / were foreigners” (54). Throughout, she mirrors the instability of our jagged history and current moment with such unpredictable insertion of italics, capitalization, misspellings, and variant punctuation (parentheses that open but do not close, sudden underscores or asterisks, colons and backslashes in the same line, etc.).

In a wonderfully heretical turn recalling Homer and Milton, Stancek also appears to reinvent the epithet with her numerous image clusters, defying the often-quoted workshop rule against using adjectives. She animates the trite “moon” and “night” with new possibilities: “utter night” transforms to “pharmaceutical night,” “gas exploration night,” and “copcar night,” while the moon sours from “moonlimp” to “putrescent moon” and “turgid moon.” These gorgeous, abject clusters become motifs that in totality clarify her critiques, though each is so packed with meaning, they can be pondered as miniature poems. Curiously, the word “of” embodies another important motif, beginning and ending many lines: “our lives patterns / of spit on / sidewalk (73). Here and elsewhere, Stancek repeats the preposition to underscore problematic patterns of ownership in a society bent on identity erasure.

Oil Spell ends climactically with a poem appropriately entitled “r.i.o.t.of,” one that begins in a less abstract way than its forbears, offering imperative directions for how to dismantle a systemic order that empowers police violence. In this poem, Stancek presents and then unravels the term “officer-involved shooting,” inferring that media exploitation of the diluting phrase obscures the true victims and story. “Here it goes watch closely,” she demands plainly, “take down the town take … the rooftops and their shining shingles … the posters the banana stands … computer chips take them computers with them take them down to the ground” (81). These rhythmic directives loop assonance and repetition with compelling chant. Yet here Stancek also projects her most serious prophesy: the “posters” of the media, and the capitalism that enables them, are responsible for racist and environmental terror. To imagine healing is to imagine or literally undertake revolt: it is to “take down the rooftops” and computers in a violent unhinging of industrial obstructions. Accordingly, the poem’s meanings then unhinge with spondaic fervor: “light light without sense sense blaring sense blooming: riot” (82). Let the murdered speak their truths, she suggests, let the “corpse chirrup” tell of where “Rune was ruin in the avalanche sun” (85).

What does it mean to feel lost in a book of poems? Are we not already lost in an “unremembering” cyber culture that normalizes “officer-involved shootings”? That dismisses oil spills and climate change? These aberrant noisescapes nonetheless shiver us into meaning, beckoning as they “invoke what is already gone” (8). With frustrated beauty they conjure with “heinous / hollow ]] remains” that “chafe / the eastern tower” (79), that become a “language contagion” echoing inside its “chapel in ruins” (37).

1. Claire Marie Stancek, Oil Spell, (Oakland, CA: Omnidawn Publishing, 2018), 7.

2. Walter Benjamin, Selected Writings, ed. Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings, trans. Edmund Jephcott and others, vol. 4, 1938–1940 (Cambridge, MA and London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2006), 391.

3. Pocket Oxford English Dictionary, 11th ed. (2013), s.v. “drone.”