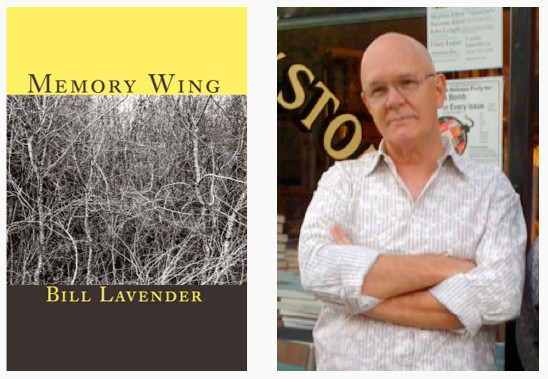

A review of 'Memory Wing'

Memory Wing

Memory Wing

When I read an acquaintance’s life writing, it seems an act of friendship not only because my experience and impressions of that person can be confirmed or amplified, but I learn new things and am drawn to consider how that person structures, omits, references cultural matters, politicizes, or not, their lives. What does the work as fiction do?

I met Bill Lavender in Madrid during 2005 after having accepted his invitation as visiting writer for the University of New Orleans International Program. It seems a prelapsarian moment — shortly upon returning to the states, the onset of the Katrina flood and destruction began. Toward the end of Memory Wing, post-Katrina and -BP disaster are referenced in despair:

and the whole big planet

teeming with birds and fish and mammals?

we could save it from the abyss

and all those species from extinction

but we’re not going to

we can but we won’t ought to be

our rallying cry the flag motto

and the poet turns to a simple paradise of feeling the sun’s warmth while lying in the grass as if it takes super-human strength to pull a tiny paradise from an overwhelming hell. But, as is often said, knowledge constructs suffering, and the greater arc of Memory Wing is a portrait of the artist as a young man — how he comes to know, how the three-part comedy of dying mother whose memory is damaged by dementia, dead father who had to be both overcome (“Father / führer / phallic ambrosial”) and incorporated, and his two sons’ birth; their utter embodiment and growth are all aspects of how Lavender articulates self-construction.

That summer of 2005 in Madrid also brought poet Susan Schultz to the UNO program, and, of course, her work on her mother’s dementia in both dementia blog and Memory Cards 2010–2011 series comes to mind. Though structured differently from Memory Wing, Schultz uses the blog format, going back in time to record daily observations of her mother’s loss of language, her children’s growth in language, and her reflections on ideas (as well as her own inability to remember until her mother’s death) results in a flood of memories of who her mother was and what made her interesting rather than those of a sad life growing ever more silent and inert.

My former teacher Raymond Federman frequently said that all writing is fiction, even history is fiction, and autobiography, too, especially autobiography. To me Memory Wing reads as a screenplay in the form of poetry: the text is a sequence of quatrains, and the diction is vernacular in lower case. A thoughtful telling, and often funny in the way being bad has its pleasures, the tone is good to hear and the ethical arc is believable. The work has the filmic convention of framing shots, first using the wing of the hospital — the memory wing — where Lavender’s mother lies speaking to the dead, not fully recognizing her son. In between, we are taken through Lavender’s memories of early years: rebelling against authoritarian teachers, a wonderful mythic snake he and another boy draped on a stick to bring back home:

it crossed the stick seven times the head

hung low tongue darting mouth opening when

anyone or thing approached momma called it

a coachwhip jet black down the tail

His other explorations led to physical punishment by his father, growing loyalties to his friends and tough lessons of betrayal — he is ashamed of not recognizing a poorer boy (later we see betrayals such as one friend “ratting out” another in a drug bust, sexual infidelities, loss of focus in some friends who had a chance at something), and a turn to the woods as his best friend, real parent, and scary presence:

running in the woods the woods the woods

were my best friend and they were the

scariest place they were where I hid and they

were what I hid from and then the wind of the

wing of something

passed over the house in the night

We are returned to the filmic framing devices: his mother in the hospital, his discussion with his dead father in part two over a log fire that doesn’t warm, and, in part three the intermittent address to his sons. In between the frames, we see and hear Lavender’s memory reconstructed, made alive. In each of three parts, we have Lavender’s experiences of sex, poetry, work, bikes or motorcycles, early reading, and literary teachers who are flawed but become more sophisticated as he grows, a few walk-on parts by well-regarded poets, C. D. Wright, for example. We also read of an early besting of his teacher to the delight of classmates as his earliest memory of what the “future” may be, his sense of audience as a challenge to power.

This is interesting because this figure is repeated later on. It appears in part two in the extended description that a friend, Brazier, gives of what it was like to attend his first Rolling Stones concert. A sequence that could stand on its own, too long to be repeated in full, it begins with Lavender and Jim Calhoun playing chess in a bar that becomes increasingly packed and loud, results in Lavender’s memorable win, then Brazier’s describing the audience that waited for the Stones to begin:

and the crowd gets quiet like it is a single

animal and it has pricked up its ears …

… close and hot and i actually started to

get a little scared felt the crush and smell

of the crowd drug-crazed ecstatic panicking

there was no place to run in case of emerg-

ency we were in this to stay it was as i said

the world itself and how does one escape

the world? and then i heard it a switch being

thrown it was click just like a regular

light switch but louder and one lone

spotlight came on on the stage right

over jagger’s mike and the crowd

hushed just like that just like that switch …

And later:

… like all these things were a single

sensation synaesthesia a single energy and that

energy was powering us all like

one heart was pumping

The audience is revisited at a Mott the Hoople concert:

signs and the arena full of smoke like some

giant pleasure dome and mott

carried us away the crowd awash

in mescaline floating above itself in a

skein of smoke and light

The lovely rebellious unity becomes politically extended as the challenge to the father-state, both as Lavender’s singular father’s “paranoid tomcat discomfort” and racism and as the collective father Nixon and the My Lai massacre created by the state:

we

on the hill above the stadium with our crosses

that spelled my lai when nixon’s helicopter passed

right over us and the crowd growled like

an animal

So in this sense the singular life is also the shared life, yet it is a different version from, say, Lyn Hejinian’s My Life. Though it’s easy to consider much of this as a screenplay, embedded toward the end is the contrast between a movie moment and life where “scenes take decades to unfold.” Even so, much does happen here in a moment: a turn to leave town that happens in a snap of the fingers, to travel, to consider oneself a writer, to understand the collective intelligence of an audience, to seduce or to sublimate seduction into a business hustle, to consider the relation of “memory to lies,” and this vision of the materiality of language:

as if to write were to build

something physical architectural that would

catch in the ground and hold while the river

ran by it

This leads to a powerfully written concluding sequence; he recalls a swimming pool game he played with his sons creating a current for them to swim against:

you might join arms and

encircle me like a gill net

but on every pass inexorably

i wiggled between you and got away

until he surfaces from this dream and sees “the little girl with your face,” his granddaughter, then concluding with the myth of the Cyclops and Odysseus, the wanderer, who is “No one.” And like all fishing around, all reconstructed selves, so much got away, yet so much is a material force to work against.