A review of 'Black Case Volume I and II'

Black Case Volume I and II: Return from Exile

Black Case Volume I and II: Return from Exile

we sing looking to ALL the past future masters

to give us clear vision

healing music, GREAT BLACK MUSIC

where we start from finish start finish[1]

Across the decades, the recordings of the Art Ensemble of Chicago, as well as most announcements of their concerts, bore the slogan “Great Black Music: Ancient to the Future.” Some years ago, in the course of a panel on the Ensemble and their history at the University of Chicago that featured Joseph Jarman, Roscoe Mitchell, and George Lewis, the subject of that slogan and its origins was broached. Asked why that slogan, Jarman quipped, “nobody ever said it was great.” Behind that simple explanation lay a history of the denigration of Black music in America, a history confounded and refuted on every stage the Art Ensemble ever mounted. The slogan also foregrounded the very future anterior that marked the Black arts of the era, from the short stories of Amiri Baraka to the astral space ways of Sun Ra. In the poem “Return from Exile,” which is the source of my epigraph, Jarman writes:

We offer

you these old new prayers

Our HISTORY

will begin ending (100)

This was truly the Black Arts outprecedenting itself, finding its future in the present, unfolding from a futurist past.

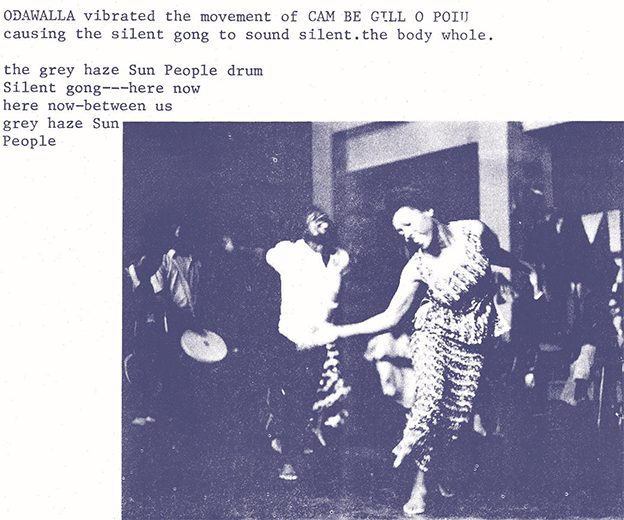

Much the same could be said of this book itself. It first appeared as a spiral-bound, 8½ x 11” collection whose publication had been undertaken by Jarman in association with his musician colleagues. In 1977, it was reconfigured as a square, saddle-stitched volume from the Art Ensemble of Chicago Publishing Company, whose glossy cover bore a reproduction of Joseph Jarman’s passport photo. I have always been indebted to Nathaniel Mackey’s generosity in providing me with a xerox of the book, which is what I made do with until I could finally get a copy of my own on the used book market. On my copy, someone had written “review copy” at the top of the copyright page in longhand, but then Jarman himself had autographed it “Peace and Love” to someone named Ron. The book has always been something of a fugitive proposition, and in her new introduction, Jarman’s wife, Thulani Davis, reports that neither she nor Jarman even had a copy at the time of Jarman’s passing. She borrowed fellow musician Douglas Ewart’s copy in hopes of getting a new edition into print, and then Blank Forms stepped forward to fill the void for us. This third edition of the work is almost identical to the second edition, save that it is perfect bound, the color of the ink has changed, and the arrangement of the words on the cover has been altered. The new book retains the photographs and musical lead sheets that have always made this an especially personal and performative collection. You can read it and, if you have an instrument at hand, you can play it. It will require some woodshedding, though. “As If It Were The Seasons” seems straightforward enough, composed as it is in common meter that should be familiar to all poets and hymn singers. But “Whats to Say” starts out in 7/4, then passes through sections in 6/4, 5/4, 4/4, and 2/4. You might need a drummer as able as Famadou Don Moye to guide you through those changes.

The newly added front matter will be of tremendous use to readers coming to this work for the first time. For any unfamiliar with Thulani Davis, in addition to her own work as a writer, she has long had affiliations in the world of the music, stretching from Oneness of JuJu to collaborations with her cousin, pianist/composer Anthony Davis, and, of course, she was an integral part of the Third World Artists Collective. Davis sketches some of Jarman’s literary influences: Baraka, of course, Henry Dumas (she recalls Jarman having memorized entire passages from Dumas), Chicago’s still underrecognized Amus Mor (Jarman speaks of Mor’s “boppish realism” [31]). And readers will soon see that Jarman had been reading along in the same places Baraka had been working: “yes ‘go contrary / go sing’” (40). Add H.D. and Amos Tutuola to that mix: “a finger pointing the way into ourselves” (123) is what Jarman finds in works like My Life in the Bush of Ghosts. Brent Hayes Edwards, who could probably have written a whole book about this instead of just the introduction, does his usually nuanced and thorough job of deepening the context for readers. Edwards sees Jarman’s Case emerging in the midst of “perhaps the most extraordinary of an efflorescence of literary publications by jazz musicians in the 1970s” (13), and he’s not wrong. It did seem for a time that every jazz musician in America saw themselves as equal parts spiritual seeker, political thinker, composer, and poet. And while much of the lyric and poetic efflorescence may have proved substantially less substantial than the music, it was also an era that gave us the writings of Cecil Taylor and Joseph Jarman. Edwards supplies a valuable footnote listing many of those publications, works by everybody from Sun Ra to Marion Brown and Leo Smith. Absolutely indispensable are notes 27 and 28, where Edwards provides readers a discography of all the recordings of Jarman and the Ensemble, in which some of these writings are recited, and instrumental recordings of works that were based on poems in this volume. You will want to get hold of all of these, especially since the recorded performances sometimes differ from the print page in interesting ways (this is jazz after all). Jarman writes: “reader you must look read yourself to hear the / MUSIC” (77). Believe him, in all the senses of “read.”

The book is in some ways a time capsule from that era described by Edwards, but like the music itself, “ancient to the future,” it comes to us from a prescient past, a fold in the continuum that should bring us back to ourselves, a return from exile. If the world is all that is the case, then the Black case does so much more than just endure, as a Faulkner would have had it. The music of the Art Ensemble of Chicago, like Sun Ra’s, like Cecil Taylor’s, was/is a sound coming back at us from our own futurity, unspooling endlessly. It was Jarman who gave us to contemplate the “non-cognitive aspects of the city.” And it was Jarman who found in “uppity the force of becoming” (129). George Lewis titles his history of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) A Power Stronger Than Itself, and that is the force of becoming found in Jarman’s life and works. His address to us rising out of the past speaks a mighty, mighty lesson today:

We want only to have

equal right to sing a great

music, just as other men …

We understand that

the music we play is difficult

for many to hear, but we also understand

that many other people want and

need to hear it. (133)

In the end, this is needful preaching to an always already becoming choir. You want to be in that number.

1. Joseph Jarman, Black Case Volume I and II: Return from Exile (New York: Blank Forms Editions, 2019), 101.