Reading 'Iovis' in Bolinas

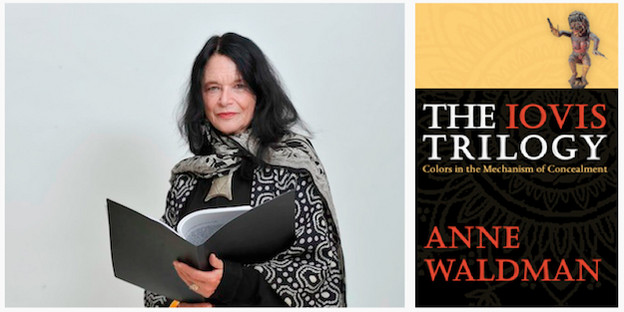

A review of Anne Waldman's ‘The Iovis Trilogy’

The Iovis Trilogy

The Iovis Trilogy

In Bolinas, California, on a sunny late spring afternoon, four of us are sitting at a small round table set for tea. The table setting is unquestionably Joanne Kyger’s: woven bamboo mats trimmed smartly in black, small dishes of nuts, seeds, and cookies, a cheese board with a local cambozola, crackers, fruit, a small tray of spicy dried seaweed, delicate china plates and silverware tipped with arabesque, and everyone with their drink — some with chamomile tea in small jade-green cups, sparkling water in translucent blue glasses, white wine in stemware — around a centerpiece of pale purple Hydrangea and a few sprigs with tiny white flowers all fringed in broad, sphere-shaped leaves. We are passing around The Iovis Trilogy, because Joanne — who is always pulling book after book off a shelf or from a small table nearby and putting them into your hands one after the other, so that you place one book on the table to empty your hands to receive another book until the table is full of small heaps of books and in need of clearing — insists that one can not read Iovis alone, that it’s meant to be read aloud: “for it was her song, & / she always wanted to sing it / moving as she did among his waves” (213). Donald Guravich, Joanne’s companion of over thirty years, who so often serves as a verbal counterpoint to Joanne’s proclamations, emphatically agrees, and we, Eleni Stecopoulos and I, having just arrived from a quick picnic lunch at a windy Limantour Beach on Point Reyes National Seashore where a horse had rolled his huge, muscular body down onto the sand, and where children rolled and ran, and sand got in our hummus, we agree, too. We have all seen Anne Waldman’s ‘Socratic rap’ at Naropa University’s Summer Writing Program, have been at her elbow for some social occasions, have seen her perform her poems with and without musicians, and sharing a sense of her, we are all one in agreement on this point. This is an occasion to read Iovis aloud.

But this is not the only point Iovis brings us to. It is, instead, Joanne, a moment ago, pulling book and stool over from the periphery of the tea zone (and this looks like a significant struggle, to move this 1,013-page book and its stool only a few feet across the floor [when “the poet positions herself in the cosmos” it’s going to be big (7)]) so that it becomes, also, another seat at the table where the four of us sit. The point is that Joanne, insisting we now in turn read aloud, reveals that Iovis is not so much “meant” to be voiced as it requires it, demands it. This book must breathe, and our breath carries its words into the verbal open. “Because I’m so enthusiastic on this logopoeia” (829).

At this juncture, while the book and its stool are being dragged to the table, I quietly point out that I have been reading Iovis alone, and it’s not so much that I’m compelled to divulge this fact as that I am struck by this coincidence, so that it feels as though there is something in this moment directed specifically toward me, a current reader of Iovis, though one who failed to follow her own disciplined agenda, which was to read one section of Iovis as a daily meditation and to thus let it accumulate in me while jotting the notes that would become the review. Reading one twelve-or-so-page section is a considerable commitment (and it would be best to really live with it, to spend all day with each section rather than the morning hour or so my schedule afforded), and with each book (published consecutively in individual volumes by Coffee House Press in 1993, 1997, and 2012) containing about twenty-five sections (and weighing in at 300 or so pages), it would take three months (skipping a day here and there) to finish. In the process of reading Iovis, my notes themselves had become epic, because Iovis, being a work of an expansive mind and heart, at so many points sutures itself to our familiarly troubled world: “suffering suffering / what is it like / graphomania” (847).

“Iovis omnia plena” — “all is full of Jove” (2), all is “full of,” ruled by, the laws and social order laid down by the male god’s principle. Virgil’s phrase becomes the initiating emblem for patriarchy in Iovis, at once a personal epistle and a highly staged response to our time of military imperialism and myriad collateral damage:

what are we dying for?

58,000 of “our own”

did die, then died on them

did die them, then

& now?

we die others, many thousands

they die on us

die on me (725).

With her roiling, roving, inquisitive, and accusatory words on our lips, Anne (we all refer to her as “Anne” as though she were here among us in her book) combats the masculine energy to which all of Iovis is a huge heave-ho. History is an unavoidable invocation “to take on the manifestations of patriarchy in writing, tracking, tracing, documenting” (xi) and, aided by “investigative travel” (xi), this project spans the globe. Iovis thus draws on and expands the modernist American epic — she cites “masters Williams, Pound, Zukofsky & Olson” (3) as precedents. And as for H.D.: the fact of her lone female predecessor is significant. It’s easy to recognize both Helen in Egypt and Iovis as acts of productive counterforce to the ideologies and imaginations that came to dominate the long poem tradition.

Above all, Iovis is Anne’s “narration of a time […], a way of being in the world” (xi). Opposite the title page we encounter a snapshot of the world Anne was born into: she is a buntinged baby on the knee of a uniformed soldier, her father; it is 1945. Her epic fully embraces this world, unflinchingly passing on the story of the tribe. But it is also passing on a family history (relatives’ letters are consulted, their memories plumbed), and this frontispiece image is echoed in the repeated references to her son, Ambrose Eyre Bye, to whom the trilogy is dedicated and who, as a small child growing into a young man, was her male-companion-spirit in writing Iovis, because the adult male story is of war and the boy-child’s is of the hope of reparation and she is between these stories, literally: “if she includes him he understands the world better, simple as that” (240). The photograph serves as a humanizing counter-image to the state of perpetual war and conflict that keeps her busy: “Here are your spoils little girl, little Annie. / Here are the spoils of war” (715). The poet’s life and its antecedents bump up against and break up and slide over one another like tectonic plates. Here is a hot, living poem.

Iovis challenges the generic boundaries of the masculine epic tradition, expands them as Anne inserts herself in it, writing a vast archive “to see how the woman poet-mind would fare and flow” (xi). Wrought through multiple formal propositions — chants, dream narratives, reportage, letters, lists, and rants — attacking from myriad angles and playing in voices, it rejects unilateral male energies and breaks open an insular American-centric vision: “Add[ing] other voices that inform and infuse a life” (xii). It proceeds episodically, but refuses to adhere to a linear temporal logic, instead pinning its “narrative” to sequential explorations of spaces, material and immaterial, through which meaning is made, inhabitance undertaken, in its epoch. It broaches the question of “what is ‘appropriate’ stuff for epic attention” (529) and even, in one of several instances of self-reflection through the lens of others, documents the front lines of this discussion in a letter from “K,” a student in a class on Olson taught by Robert Creeley, which reports on his dismissal of Iovis (Book I was then in print) as too “personal” to be an epic (370). As a conscientious citizen, “Anne-Who-Grasps-the-Broom-Tightly” (15) attempts to be fully aware in a time of innumerable social inequities and injuries. As a Buddhist, Anne compassionately responds. How can one (a woman) assertively be in the world and not take any of it personally?

As I’m sitting at Joanne’s table, I’m realizing that this visit for tea in Bolinas has unexpectedly offered an opportunity to rightly read Iovis, and no one is paying any mind to my tiny confession, drawn as we all are to the book (feeling the pull of the book pulled over to the table). And I do mean we are drawn as readers of Anne. And we are drawn, in this moment, by Joanne, into a community. Joanne opens the book by what logic I know not to Book III, somewhere in the middle of section XIX, “Matriot Acts,” in which Anne plays the legislative and theatric senses of “act” against each other. Somewhere near where I had put the book down a few weeks earlier (I had put the book down on section XIV, in fact, but the nearness is uncanny enough to reconfirm the notion that there is something in this moment directed specifically toward me), and passes it to Eleni on her right, and we begin reading aloud, first Eleni, then me, then Donald, then Joanne, reading a page and passing the tome to the right. We land down past these words — the solid zigzagging line down the middle of the page effects the sense of its having been torn in half and reunited:

\ She will write out a new creed for

the protection of all the animals / therein And the entire world &

the nations therein & the trees, \ the greenery, & so on therein” (901)

We land down past these words — and we run along with them. We listen inwardly, laugh, perform for each other and comment and hear through each other and this collaborative reading becomes consistent with, threads into and out of, our conversation, the one we were and are now having, sometimes as a group or broken into pairs or in threes (when hostess Joanne temporarily leaves the table), our words resonating, not always pointedly, with different stratum of Anne’s words — “When you think about it what are the stakes? The end of Nature, the end of civilization, a truly inhumane Dark Age if this keeps up on the horizon …”(918) — for someone had said she felt we were entering a new dark ages, and someone else responded that we’ve been there for a while.

The breadth of Iovis is huge, spanning a spectrum pegged down on one end by the prose that prefaces each individually titled section noting the events personal, national, and global that create the lived space-time of the text that follows. On the other end, not so much pegged down. The page is energetically inhabited anew through an array of textual strategies: prose in various forms, poetry stanzaic and idiosyncratically spaced, the whole range of typographic marks on your keyboard deployed in signification, hand-drawn images, photographs, and collages, are but few. Even within one section, the words are rendered through a shifting subjectivity: sometimes I, sometimes she, sometimes another; sometimes female, sometimes male, sometimes androgynous; sometimes pedestrian, sometimes psychotropical, sometimes theatrical, sometimes scholarly, sometimes prophetic, sometimes not-quite-nameable. Reading Iovis requires an act of faith. You have to trust not only the poet but your experience of your own moments of dark and light or uncertainty and clarity that the poem recalls or opens up in you. Take the imperfect alignment of prose summary and poetic text to announce that there can be no single lens onto this multiple, shape-shifting, knowledge-and-subterfuge-investigating text. She cannot “read” her own unfolding journey to provide a succinct summary — it remains an open text written by “an open system (woman) available to any words or sounds [she’s] informed by” (1).

Whatever the time/space consciousness a section springs from, the overall effect of Iovis is to make visible the previously covered-over or unimagined female heroics of deep inquiry, replete with all the critical and responsive mechanisms that could possibly entail. And it’s clear that the heroics of deep inquiry are those of listening: Anne delves into a wealth of histories and cultural materials and delivers up in Iovis multiple myths and daily lives, so that, for instance, we learn in detail aspects of Hindu texts and temple rituals in one section (“Because life is short / & suffering is infinite / we study the Texts / to keep a shine on our universe” [437]), while another explains Beat generation gender dynamics (in the form of a letter to one Jane Dancy), while another reports on acts of domestic terrorism, provides a ballistics lesson, and “call[s] upon the President of the United States to reassess the easy availability of guns” (365). Iovis is the multimodal poetic equivalent of a people’s history of the world, striving to reach back and through its many beginnings: “I come here trembling, to remember how we studied the past to understand the future. Remember?” (727). Says the book’s flyleaf: “Iovis goes beyond the old injunction ‘to include history’ — its effort is to change history.” Indeed. When we read together, we become community theatre, all creative potential. “You will be a community of eyes. And you will create the world in your heart” (329).

On the page that I read I encounter “Invoked here then, was a host of fluid active female principles in the imagination and psyche of public space” (918) — and I stop to comment on it, voicing my reviewer’s mind, that here we have an articulation of the very heart of Iovis, of what it is “about,” how it is driven by an ethic to publically act — to write, teach, investigate, enable, organize, demonstrate, document, and perform, often ceremoniously — to act as a counterforce in an age guided by war and seemingly bent on destruction. This Anne lives in how she conducts her life as academic program director and global emissary and poetic community member, and Iovis is bound up with that, a part of this cloth, is her daily experience and thoughts and readings and spiritual practice and travels, so that Iovis is, grandly, a millennial poetics, a guide to being a poet of this world now-as-it-is-and-got-to-be, offering lessons in mastering “weapons like articulate speech & poetry, beauty” (154) — and this, if you read even a small slice of Iovis, you find made in its pages.

We are lovely people for each other when we read Iovis together. We are forces of good together; we witness for each other and together what is and what may be imagined. Together we witness as Anne experiences and imagines, as she assembles and teaches and indeed it feels as though she has materialized among us when Joanne performs her page in Anne’s deep down voice and with Anne’s dramatic hand gestures. Then we have all read. We commend Joanne for her idea, and agree with her, it must be read communally. Donald says you can’t read it silently, it won’t come off the page, it has to be read aloud, it’s the fact of the book. He’s right, we’re all right in that moment, and I’ve been reading it all wrong, sitting alone, silently absorbing, as though I could be a giant sponge to it all, a critical sponge that can pull out pertinent passages to stud the review I imagine I am writing. It’s simply too much to take in alone. It’s a culture, it’s many cultures, it’s your culture with the face of the thunderbolt-bearing head-of-statesmen sky god Jove. And you’re in it, and you draw it into yourself, which is not advisable, you need the space of other voices to bear the burden, the way Anne needs Kali, goddess of time and change in her benevolent guise, to “resume a dark shape. Fade into the street, down the alley, be invisible. Be the small shadowy quiet thing you are” (919). As Donald read these sentences, I felt again as though there was something in that moment directed specifically toward me. But isn’t that the sign of a great epic work, that we feel articulated in and through it, and surely there is something for anyone on even one page of all of Iovis. With its energies animated on the breath of its readers, it is how we acknowledge, is our communal, public voice. At the heart of the epic Anne insists, “Community is ‘voice’” (2), and through her insistence (and Joanne’s) “one” is invoked into “we” through the words of Iovis. But that is not all. “This is everything, this is nothing, this is not a conclusion” (831). With its energies animated on the breath of its readers, it is how we make space and, how, most importantly, we, along with Anne, create a cultural document, “leave a trace so that poets of the future know we were not just slaughtering one another” (656).