The posthumous now

On Hillary Gravendyk's 'The Soluble Hour'

The Soluble Hour

The Soluble Hour

How do we read the work of poets who die young? Recent books by Joan Murray and Max Ritvo have me thinking about the question with a special intensity. Ritvo died of Ewing’s sarcoma in 2016 at just twenty-five, with two posthumous volumes — The Final Voicemails: Poems and Letters from Max — published last year.[1] Murray, who won the Yale Younger Poets award, died at nearly the same age, in 1942; Drafts, Fragments, and Poems: The Complete Poetry has just been painstakingly edited by Farnoosh Fathi and published by NYRB Poets.[2]

In his 1947 foreword to Murray’s Poems, W. H. Auden, who had been her teacher and mentor, exhorts us “to approach her work just as objectively as if she were still alive, and not be distracted by sentimental speculation about what she might have written in the future which was denied her.”[3] It’s hard to imagine today’s readers adopting that icy stricture, even if it reflects the poet’s own wishes. Auden hoped to fend off the assumption that the poems were published “out of charity.” If they’re good, he believed, they don’t need special pleading; if they’re not, they shouldn’t be published.

But poets who die young, without the ballast of a long career, need luck in their readers to keep from floating off into oblivion. Murray found Auden and, later, John Ashbery; their attentions kept her name alive for younger poets like Shanna Compton and Fathi to discover. Ritvo studied at Yale with Louise Glück, who edited The Final Voicemails, and at Columbia with Lucie Brock-Boido. Along the way, also at Yale, he struck up a friendship with playwright Sara Ruhl; their correspondence forms the core of Letters from Max. Contra Auden, these chains of transmission are a vital part of the poems’ story, and we’d lose some of our purchase on the work — on how poetry works — without knowing them.

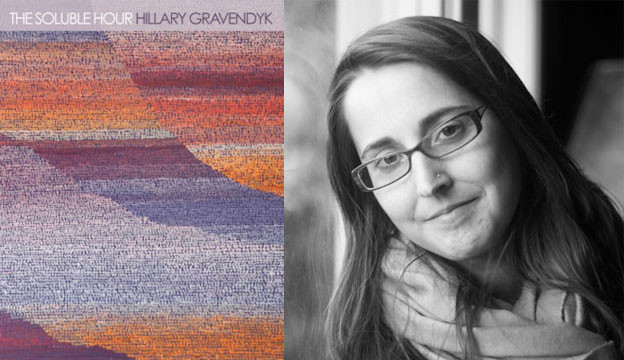

But what weight do we give to that story in reading the poems? How much should it color our sense of the writing? It’s with these thoughts in mind that I first read Hillary Gravendyk’s The Soluble Hour. Like Murray’s and Ritvo’s, it’s a posthumous collection. Gravendyk died in 2014, at thirty-five, outliving by more than fifteen years a prognosis she received at the age of nineteen. As a graduate student in Berkeley, she came into the ambit of teachers like Lyn Hejinian, Brenda Hillman, and Robert Hass, all thanked in the book’s acknowledgements. The task of editing her last work fell to Cynthia Arrieu-King, who describes their friendship in the introduction and explains the decisions she made in assembling the collection. It consists mostly of poems found in a file on Gravendyk’s computer after her death. In consultation with Gravendyk’s husband and mother, and with input from Omnidawn’s publisher Rusty Morrison, Arrieu-King removed a “slight few” of the poems she found in the file; included recent poems from different computer files; added some older pieces; divided the book into sections and chose the title.[4]

Interventions like these can set off warning bells. At least since Emily Dickinson, tales of the maverick writer tamed for publication by well-meaning editors are legendary. In sorting through Joan Murray’s myriad drafts, Fathi confronted the valiant but questionable decisions of an earlier editor, Grant Code, in her effort to bring the poems closer to their wilder originals. Louise Glück allows in her preface to The Final Voicemails that “it was slow work to sift out the very best” from Ritvo’s unpublished poems; an “essential labor,” she tells us, “lest the weaker dilute the stronger.” Yet “this he asked me to do.”[5]

Arrieu-King’s labor on The Soluble Hour entailed sifting and sequencing, not revising lines or choosing between variants. But the book, as surely as Murray’s or Ritvo’s, is partly an act of editorial creation, necessarily dependent upon a sympathetic guess about what the poet would have wanted. Bucking Auden’s scruples about using the life to frame the writing, Arrieu-King commends the work as “some of — if not the finest — poetry about illness written in American letters” (11). Stressing how the poems were “made from a life of medical procedures, embodiment, and love,” she hears Gravendyk’s “lyric voice” as one pitched to “evoke a sense of time as being both too short and eternal” (12).

The fascination of poetry written from illness has something to do, I think, with exactly this altered time sense. It’s hard not to ascribe a special knowledge to poems written under the immediate pressure of mortality. The feeling that time’s short, that the present needs to bear more weight than we ordinarily ask it to, imparts a gravity, even majesty, to lines that could feel abstract or merely literary in another context. “You cast / a handful of shadow / against a bare tree / strike a warrior stance” is the book’s opening phrase, evoking both struggle and evanescence (19). “We’ve collected failed remedies. … Pain lit up like a traveling circus” (22) and “garland of bruises / adorn the bone and tendon / at the hinge of my rising and falling” (62) suggest surgical procedures. Other lines read like rehearsals for the poet’s imminent departure: “Raspberry-lipped summer, I gave you up like a loose promise” (21); “‘goodbye’ gets repeated until it becomes our politest greeting” (66); “I understand transformation better than death, though / I practice for it every night, with you” (39).

Once you start reading the poems as documents of a medical crisis, nearly any image of loss or ephemerality, from a change of seasons to a half-remembered dream, can look like “practice” for the poet’s impending death. But this wide interpretive road can lead into a cul-de-sac. It allows the poet few themes outside her diagnosis, confining her to a subject from which the poems were quite possibly meant to be a release. This seems especially true of a writing so committed to border states — the “poised between,” as Gravendyk puts it in “Whistle Stop” (69) — that aim to hold both writer and reader in a state of phenomenological suspension, a“waiting, ringed with rocks / and purpose, Daphne at the water’s / edge” (31). Her embrace of uncertainty and open-endedness, the wait for an elusive meaning or transformation, like Daphne’s, that hasn’t yet arrived, are all familiar features of the postmodern lyric, growing up from its Symbolist roots. But knowing Gravendyk’s ultimate fate — and knowing she knows it as she writes these lines — orients the reader’s attention differently, within a ring of “rocks and purpose” that seems to border her poems and set them off from the commonplaces of contemporary verse. You feel these aren’t language games or theoretical positions; they’re the substance and gestures of a too-short life.

That life shapes the art most profoundly, I think, in Gravendyk’s expansive approach to the lyric subject. Her poems tend to emphasize their speakers’ habitation in a body. Mouths and necks, fingers and skin, bellies and chests, “the tender spine” and “the fragile vein” (62), faces and tongues and (especially) hands recur throughout The Soluble Hour, reminding the reader that the voice in these lyrics issues, always, from a physiology. At the same time, the body in Gravendyk’s poems — most often appearing in parts, rarely whole — possesses a metaphorical quality, as if it’s already a trace of itself, visible as a pressed hand on a “rosy pane” (66); or an image “in a mirror the color of Scotch tape” (78); or a “landscape that refuses to forget,” where her lover (and future readers) will need to learn to find her (34).

In particular, bodies in Gravendyk’s poems metamorphose easily into figures of ecology. In “Summer Storm,” she imagines “your body a quiet island / in a quieter sea” (30). “Then birds rush from your throat singing and falling” in “[I carry your taste as if it were a stone]” (28). In “Now Sun, Now Surface,” “a rib moves like a sparrow” (65); “Whistle Stop” describes “the way water blooms into a sudden body” (70). As the book goes on, these formulations accumulate with an almost obsessive regularity: “your body like a streak of sun, smeared across my face and chest” (27); “Mossed belly, strewn hillside, earlobe” (29); “forever bound to our / bodies, which falter, which spring up fern-laden groves, which flower / and fail” (42). Like the figure of Daphne, Gravendyk’s subjects most often exist — seem to exist most fully — at the limit between two states, at once themselves and anticipations of the things they might finally need to become.

By the same token, objects and concepts in The Soluble Hour, like in medieval cosmology, often mimic features of the human body. A vale bears a “dark mouth,” water “blooms into a sudden body” (70), limbs appear “like an archipelago on a sea of white foam” (32), the poet holds “sound / like the crook of an arm” (37). Even the lyric itself, with its “tiny numerous folds,” assumes a somatic shape (69). “Only the lake is beneath the lake,” the speaker reminds us in “Whistle Stop” — a flat signifier, pointing only to more of itself (70). But the cumulative effect of Gravendyk’s poems is to charge the world with significance, in the deep sense of the word: calling into being a state in which bodies, organic or otherwise, always carry the potential to signify.

The stress in these poems on the capacity of bodies to mean — on bodies as conduits for meaning, like words, transmitted from the lyric to the second-person “you” so many of them address — strikes me as a moving assertion of faith. A faith, on one level, in the poet’s power to remake self and world through the symbols she uses to describe them. But a faith too in language itself, its ability to carry, for all its slips and limits, the sensory memories and, most vitally, the love the poet wants to bequeath to those she has to leave behind. “You try to catch hold of it all,” she writes in “Summer Storm,” a line that captures one facet of her poems’ ambition (30). Instead of a postmodern record of its own failure — of the body’s failure — Gravendyk’s last work reads like the consummation of a spare but lush serenity, “sweetened into bareness” (23), which over the course of the sequence mounts to a kind of wisdom. “I was the storyteller, stumbling on separation,” she writes in “Quarrel” (25). She’s more persuasive for acknowledging the stumble, but in the end it’s the story (and its teller) that has the final word.

My favorite poem in the book is “Fairy Tale.” It’s built on a ladder of anaphora, each line but the last beginning with the phrase, “I taught.” In assuming the persona of a hero in the “half-light” world of fable, Gravendyk allows herself a range and swagger reminiscent of Yeats’s Fergus (“I have been many things — a green drop in the surge, a gleam of light / upon a sword”). “I taught the downfall and I taught the jubilation,” it opens:

I taught the carriage horse, sleepwalking its route.

I taught the promise and I taught the incantation

Taught a three-part harmony, whistled or sung

…

I taught the truth and I taught the mistaken

I taught the gathering and the suspension

I taught you a message to carry in winter

Taught you the waters that rustle and creak

…

I taught you the secret, the mystification

Taught you the candle the bell and the book

I taught you, at last, a story for tellers:

Loss always has time for you, if you wait. (24)

With each iteration the poem affirms, under the cover of fairy tale, poetry’s ancient and eldritch power to teach. Part of the attraction of last testaments like Gravendyk’s is how they stir the old, visionary desire for poetry to impart truths other forms can’t. And arguably poetry’s most elemental truth — the one at the heart of poetic journeys from Inanna to Orpheus, Demeter to Dante — is that which the dead bring back for the living. Gravendyk eschews the spangled mantle of myth, but in the modest garb of fairy tale (what wisdom wore to survive the Enlightenment) she reaches an insight just as weighty. It’s a “story for tellers”; one for us, her readers, that we can pass on or tell ourselves to fill the absence only language fills, in “the gathering and the suspension” where the poet’s truths reside.

“Nothing guides you like the thing that leaves you,” Gravendyk tells us in The Soluble Hour (28). The story she leaves in these poems doesn’t offer up an antidote for loss, which, in the end, “always has time for you.” There are no returns or resurrections in her work, no intimations of an afterlife. But through her rhythmic repetitions and command of imagery, the finality of loss begins to feel soluble: capable of dissolving, but also of being salved, or solved, in the consolation of the poem, which, like memory — like all commemoration — is exactly as temporary as we choose to make it. Gravendyk’s poems are finally not so much a monument to her own disappearance as they are a set of messages left behind for us, inscribed with the paradoxically life-enhancing moral that“one should always be reminded of being left” (66).

What will happen with books like Gravendyk’s, Murray’s, and Ritvo’s? Will they change the story we come to tell about their literary era? Will they stay guild secrets — as Murray did for decades — or end up in future anthologies, revealed as key voices of the time? Maybe they’ll exist, like so many poems do, as suspended possibilities, available to future poets looking to slip whatever canon their age has imposed. What moves me most about The Soluble Hour is the way it subsumes this literary question of a poet’s posthumous existence into a more urgent and particular meditation on what it is she can leave behind, through the medium of language, for those who loved her. It’s a virtue of Gravendyk’s work that the one provokes reflection on the other, like in allegory: same shape, different waves. With The Soluble Hour, she’s left a sensuous, affecting reflection for those who knew her. If it’s not too remote from her own intentions, I hope it also finds her the wider readership she deserves.

1. Max Ritvo, The Final Voicemails: Poems, ed. Louise Glück (Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2018) and Max Ritvo and Sarah Ruhl, Letters from Max: A Poet, a Teacher, a Friendship (Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2018).

2. Joan Murray, Drafts, Fragments, and Poems: The Complete Poetry, ed. Farnoosh Fathi (New York: NYRB Poets, 2018).

3. W. H. Auden, quoted in Murray, Drafts, Fragments, and Poems, 246.

4. Cynthia Arrieu-King, quoted in introduction to Hillary Gravendyk, The Soluble Hour (Oakland, CA: Omnidawn, 2017), 12.

5. Louise Glück, quoted in “Author’s Note,” Ritvo, The Final Voicemails, xi.