A point of view where there are no voiceless people

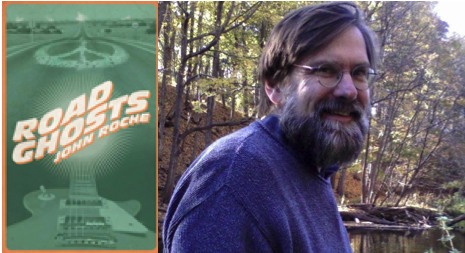

A review of John Roche's 'Road Ghosts'

Road Ghosts

Road Ghosts

John Roche speaks to the ghosts of the road he traveled as a teenage runaway in the early seventies. He rescues their stories, recounts their lives. And, for his unwavering stance as a critic of social and economic injustice, this American poet hitchhiked, tasted Southern “hospitality,” was jailed, held the magic wand, read Yeats by firelight, revisited Route 66, sang the song of the wandering Owlsley, departed El Dorado, and passed over the Rainbow Bridge with psychotropic colors.

In his new book of poems, Road Ghosts, the concerns of those times are on full display: the way the powerful trample the powerless, multinational corporations upending the less privileged, and political thugs erasing history and pesky citizens. Roche, at times, can be described as a magical radical — one half reason, one half passion, and a third half mystery. Blending memoir with political analysis, taletelling with cultural critique, he writes all these things and more, making that part of OUR history all the more writ large.

I was a suicide bomber at seventeen

Taking my holy mission on the road

Planning to detonate on Nixon’s front porch

But having to settle for a detention camp with habeas corpus revoked.

In this poem, “Prologue-Suicide Bomber,” Roche offers snatches of his own early life, one threatened by Ohio refineries, Indiana chemical plants, the atrocities of Haymarket Square and Wounded Knee, burning cities and rank militarists. He survived it all; he tripped on organic mescaline,

Stumbling on in a blurrr

Of campfires an rock-n-roll and returned vets and

Hippies who haven’t returned and bikers and

Patchouli-scented girls

Easy Rider meets Apocalypse Now orgy

He wanted to give everything before death came, to empty himself, so that old night couldn’t find anything to take.

He wrote “Before May Day,” an epic history of two weeks in tent city, West Potomac park, as if to reclaim all that he (read we) had lost, and with a vengeance. He relates those days of “Bring The war Home,” the “chill April night” of Vets throwing their medals over the White House Fence, “Vats of hot marijuana tea, Seatrian concerts and the fiddler’s anarchic orders.” Roche boils down the government that won’t stop the war, while speaking for the disenfranchised, those waiting to get out into history.

Educated and self-educating, at once wounded and wise, with a survivalist’s appetite for life, Roche writes from the point-of-view of that middle-class boy back in the seventies. After all, point of view is essential to writing, to life. For Roche, it’s an anchor. But, whereas anyone who has gone through (put themselves through) a slice of history can be tempted to see it from the point of view of a worm, where a spaghetti dish could be taken as an orgy, he confirms a bigger mission of tenderness, a point of view where there are no voiceless people. It is his intention to hear the voiceless coming from those who for such a long time had not the right to be heard. Sometimes he voice is almost hushed, as if to counter the tenor of his rage:

Go up to the ramshackle store

Single gas pump out front

Ask directions

Owner says, Bet you’re one of those

Communist protestors-

I hope you never get home.

Divided into five different “roads,” this book is a series of cycles, which at times puts the seventies on trial, condemning those who accept a “reality” that rejects the poor, and that time that allowed globalization to further reduce humanity to entertainment, life to spectacle, and news to advertising. It’s easy to forgive him his didactic moments, as those were a part of it for us too. Still now he has a lot to be angry about, pumping it out with the energy not unlike the late Jim Carrol, as in “Here’s For All”:

Here’s for

The Vietnam poet skulking in the back of the hall.

Here’s for the tenured Beat Poet playing

Jazz real

Loud in his office, or the one who shouts GO AWAY!

There are images in Road Ghost in which the writing is of a beauty almost breathtaking. There’s a description of a 1:00 a.m. congeries between poets sharing “sacred bread and wine and cheese / our faces scrubbed bright as Blake’s children / we launch filament after filament / into the ether.”

If Road Ghosts wasn’t a collection of poems, it could easily stand in for a novel, a generous piece of tender and tough writing, stripped of affectations that in a novel can sometimes verge on bathos. But, as this is poetry given to the punctuation of poetics, Road Ghosts is much more devoted to the rules of music, which makes all those ghosts of time, memory and desire implicitly more immediate and even contemporary.