A poetics of appropriation

A review of William Fuller's 'Hallucination'

Hallucination

Hallucination

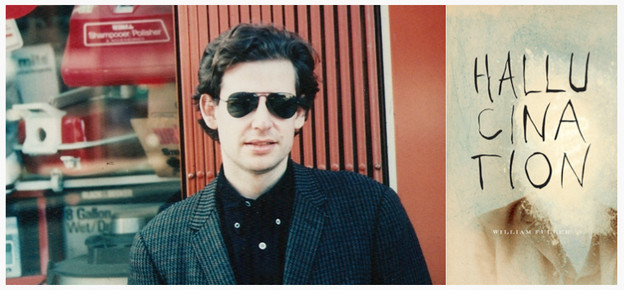

Like the obscured, faceless old portrait on the cover of William Fuller’s new volume of poems, Hallucination, it’s difficult to pick out an overarching voice throughout this collection from Flood Editions. At an organizational level, there is a noticeable divide between the prose works and those set in verse, so much so that the book almost feels as if it were written by two different poets. This sense of different writers or speakers amplifies on the poem level as Fuller appropriates various forms of stilted language, from stodgy academic phrases to business memo boilerplate. Chief fiduciary officer by day and poet by night, the Chicago-based Fuller keeps his intentions neatly hidden with Hallucination, which may be intolerable for some readers. However, to lighten things up, Fuller’s speakers occasionally sympathize with the reader by drawing attention to their own inability to make sense of the world around them. Over three sections, Fuller’s Hallucination makes full use of shifting speakers, simultaneously identifying with readers and pushing them out using declarative statements that don’t declare anything logical.

Section 1’s shorter prose work “You and Your Spies” exemplifies Fuller’s many speakers and use of appropriated language. The poem begins by poking fun at conventions of academic writing:

There is a case to be made for listing things about which we do not care. A point of confusion arises regarding order, where order is nothing save a faint posthumous beat signifying — what today? Signifying both. Both an intensity armed against slackness, and a stylish meandering near boundaries. (24)

Fuller’s wry humor comes through in these lines, as he appropriates the certainty and conviction that characterizes academic writing and turns it into a nearly meaningless clump of words that sound like they were picked up from a stack of rejected scholarly essays. However, always firing on multiple levels, Fuller cleverly replicates the same sense of confusion and bewilderment felt by readers of his work in the phrase “A point of confusion arises regarding order” (24). And can’t Fuller’s practice in general be described as a “stylish meandering near boundaries” of various forms of writing, with the poet appropriating phrases he likes along the way? Besides the academic satire of “You and Your Spies,” Fuller also borrows phrases from government reports and psychoanalytic texts: “Stages of avowal are managed consecutively, if state law allows. Many older organisms tend to be self-governing, and no amount of reflection can unscrew the basic template for their embittered sentience” (24). These sentences feel stable and certain, like their meaning should be immediately clear. However, Fuller’s hodgepodge of appropriated language from psychoanalysis (“stages of avowal,” “embittered sentience”) and government reports (“if state law allows,” “many older organisms tend to be self-governing”) completely undercuts any expectations of clarity while creating humor through the improbable combination.

Fuller uses these nonsensical declarative statements heavily throughout the prose poems of Hallucination, making for a wonderfully disorienting reading experience. Regardless of the reader’s confusion, Fuller’s speakers frequently chime in with their own, giving his poems (which feel initially impersonal) some sense of sympathy for the reader. As a speaker remarks in “Blood Red Roses,”

Their faces and bodies are changing in ways I can’t follow. […] Inside daylight a false daylight waits, and they are drawn to it. They have no power to retain their own structure, and have been advised that this is the case. They eat burnt flies’ wings and bed down on diatoms. Overlooking their lunar otherness, I catch glimpses of sandy shapes, walking or crawling. Beyond them, whalefish blow, and I see a cold gem ripening. (56)

It’s unclear what this speaker is describing — sea creatures? a lunar landscape? — yet these simultaneous feelings of bewilderment and awe duplicate the experience of reading Hallucination.

The white elephant lurking in Fuller’s poetry is his relationship to the corporate business world in which he works and which makes fleeting appearances in Hallucination. The office setting crops up in the volume’s clearest work (“The Circuit”), and Fuller elliptically references the corporate world throughout the collection by lifting phrases from memos and other office documents (74–75). The easy reading of his inclusion of these details is that Fuller is satirizing a corporate culture that he sees as soulless and stifling. However, Fuller is more self-aware than that knee-jerk reading. In a long interview with Eirik Steinhoff originally published in Quid, Fuller said, “I don’t see them [people in the business world] as manipulated by a discourse whose motives they don’t understand — many of them have acute understandings of the most subtle nuances of that discourse and offer hilarious insights. So to stand outside and comment ironically on the whole of it would seem adolescent to me.” Accordingly, it’s not accurate to read Fuller’s occasionally chuckle-worthy interpolations of business language as pure irony: Fuller knows that he is just as much a part of that world as anyone else working at the Northern Trust Company, so his tone is not biting irony, but something lighter. The report that grows to the size of a planet near the end of “The Circuit” reflects on the day-to-day strangeness of any job and 9-to-5 life more broadly, and not just the corporate business world.

Despite their relatively uniform appearance — one thin, left-aligned, centered column descending on the page — Fuller’s verse poems in Hallucination are harder to pin down. For the most part though, the verse poems contain less clear appropriation than his prose works, and they make it difficult to confidently pick out settings. “For the Lawful Heirs” seems to portray wealthy residents of Chicago’s northern suburbs, but only because the prose poem on the back of the page is named after Tower Road, one of the major east-west thoroughfares in the northern suburbs (25–26). Together, “For the Lawful Heirs” and “Tower Road” work as gentle indictments of wealth and privilege on Chicago’s north shore, or really anywhere. Other verse poems have less obvious subjects: “Morning Sutta” and “Earthly Events” show Fuller’s fascination with obscure, dated language (no doubt inspired by his study of seventeenth century lit), while “Treasure Hidden Since” finds Fuller’s imagery decomposing over the course of the eleven lines, all the way from the grandeur of a state down to a filament (27; 18; 37).

These verse poems at first feel radically different from Hallucination's prose poems, but there are linkages. For instance, Fuller is still at work pushing the reader out from pinning down definitive readings by using obscure language and unsteady, shifting poetics. However, in his verse poems, there usually isn’t a speaker to express the confusion of the reader, making these poems less sympathetic in a way. The wild turns of imagery that characterize Fuller’s prose poems definitely crop up in the verse poems too, and are perhaps more noticeable. For instance, the prose work “You and Your Spies” has only one major swerve at the end, in which the speaker declares, “I’m looking for a vale to wander in, a vale of views enjoyed as much as for their beauty and sweep, as for their way of adapting themselves to states we can inhabit simply by bending our knees. And once having found it, I won’t return” (24). Conversely, the associative verse poem “OK Jazz Funeral Services” is a poem full of these turns in imagery. One indicative moment:

[…] enclosing birds

who listen out of strangeness

then posthumously descend

great flocks of them

migrating nine miles

through a silvery drainpipe

to the demonstrated absence of a material fact —

hence these baskets (6)

Hallucination isn’t easy to read, and in fact, it’s probably good to have a dictionary nearby while doing so. But this unsteadiness only adds to the reading experience. Like the amorphous shapes at the end of “Blood Red Roses,” Fuller’s poetry also refuses to hold form. The poems twist line-by-line through various settings and appropriated languages, making for a dizzying reading experience at times. Despite the unsteadiness, Hallucination hangs together in a weird way, or at least it seems to. Fuller does his best to push us out from pinning concrete meanings to his poems and his language in general, but he’s not cruel about it — the speakers are just as confused as we are at times. As a speaker in “Blood Red Roses” puts it, “For several years now I have considered words and phrases in isolation, but have fallen short in being able to construe what they mean” (56). Hallucination exists in that place just shy of attaining full understanding, yet Fuller makes our attempts to reach clarity thoroughly enjoyable.