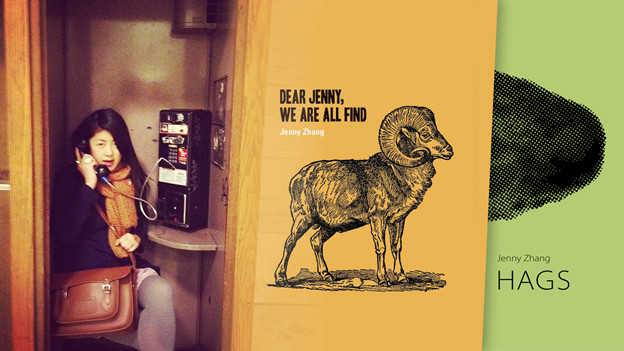

Poet in profile

The scar lit district of Jenny Zhang

Hags

Hags

Dear Jenny, We Are All Find

Dear Jenny, We Are All Find

The Year of the Ram is the year to celebrate the Black Sheep. Jenny Zhang is the New Girl fed up with the Old World crap sheet. Eschewing the coyness that makes the big wigs cream their pants, this Chatty Cathay takes her chances befriending the fierce whores, sodomites, and other forbidden scribes.[1]

Zhang is a far cry from the model minority who genuflects at the picket fence of the L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E schoolhouse. She follows in the wake of other sister artists who have adapted the lessons of the willful sissy to their own feminist battles, when the brutes or happy housewives prove unhelpful.[2] (The vitality of such a tradition in the post-fifties avant-garde is the subject of Maggie Nelson’s Women, the New York School, and Other Abstractions [University of Iowa Press, 2006].) Asked to characterize her own style, Zhang replies, “Occasional Sensualist, because my poet boyfriend used that word, and I wanted to be his twin more than I wanted to be his lover.”[3] Twinning with each other has meant absorbing the syntax and synapses of their gay poet uncle Frank O’Hara. With daily derring-do and over-friendly melancholy, she courts the misfits past and present who recognize the difference between her vagina and her voice — and sasses the ones who don’t.

Martial farts

The precocious daughter of Chinese immigrants, Zhang (pronounced Jung) emigrated from Shanghai to New York at the age of five. She describes how she was raised by spectral Asiatic hags, as her mother frosted donuts during the graveyard shift and her father put himself through grad school by delivering takeout to Wall Street. Beside her mild-mannered parents, the daughter cuts the striking figure of the punk flâneuse and scrappy burlesque queen who had to kick the softie pianist offstage to discover her true calling as a wordsmith. A graduate of Stanford University and the Iowa Writers Workshop, Zhang has taught high school in Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx. Through her articles and short stories for various webzines, she continues to lure a younger audience of teens and quarters to the candy cottages of the indie prose and poetry presses.

Her latest publication, Hags (Guillotine, 2014), is a feminist manifesto clad in the fleece of a confessional essay; its chief aim is to spin out the artistic implications of the unmarriageable biddy or proud slut of yore. Against the running gag of the “crazy-ass bitch” favored by American media, Zhang has assembled her own pantheon of heroines, anecdotes, and cultural practices highlighting the fierce dignity the hag enjoys in Eastern — and to a lesser degree Western — cultures.[4] Among her many jottings include the Chinese tradition of spirit marriage (ming hun),which ensures the wise crone a mate in the afterlife, and the Filipina lore of a penis-snatcher, a legend she picked up as a former labor organizer for Asian home and healthcare workers in San Francisco: “These hags, these great beauties, these mermaids who taunt, who feast, who slash, who steal, these succubae who cannot rest, my mothers, my sisters, my unborn friends, my keepers, my guardians” (13–14).

Zhang consequently embraces street theatre and the confessional burlesque as genres in which the flaming hag eclipses the ditzy and defenseless model. Detonating her martial farts on a subway car of Wall Street types, giving a leg show from the backseat of the family car, shoving cucumbers from the crisper up her cooch, she enacts her original choreography of hag-hood in the conviction that the squeaky shrew has a better chance at “farting imperialism into oblivion!” Then too, she likes to upset convention by showing up to a Slutwalk in her normal clothes, “betraying all the heroic sluts” who enable her own “magnificence” (16, 15). Insofar as the hag describes a set of traits that the dominant culture prefers to airbrush out of its female pinups, women of color and women of size should not be so quick to disown the charismatic label that assures them voluble visibility, as other self-appointed hags — and fag hags — have pointed out.[5] In her poetic debut, Dear Jenny: We Are All Find (Octopus, 2012), Zhang flashes her Fine China, honoring the friends and family who coax out the haggy virtues of her beautiful irritability, while zapping the smiley viruses of shameless appropriation.

Donuts and daisy chains

Central to Dear Jenny (Octopus, 2012) is a drama of selective acculturation: sorting through the involuntary culture of one’s origin and the willful culture of choice, one discards the odious assumptions of each and learns how to inhabit the best of both worlds. Zhang tells this story through the interdependent poetics of donutsanddaisy chains: “my family tree turned into a dam,” the donut is the Confucian choker of obligation that enjoins son and daughter to shore up the circular walls of the dynasty (9). The donut has the same genitive syntax as the snarl of relations one finds in a puzzle book by MENSA. It can go parodic, as in “my sister’s accountant / and your mother’s doctor’s secretary’s gardener / … is my sister’s accountant’s sister” (43), or sincere:

I don’t want to stumble anymore

I don’t want to drive anymore

Then a boy my father’s age kisses me

And a boy my brother’s age kisses my mother

And my mother puts her leg on my leg

And I’m free and anyone can know me. (93)

Even as Zhang marks her distance from the Great Wall of doctors and accountants, nerds and bad drivers, she finds ways to honor the ancestral family without necessarily endorsing its circular, risk-averse notions of the good life. She has a knack for inventing gestures that render more agreeable to the feminist the rituals of familial deference, or in other places, sexual domination. The mother’s leg touch is affectionate without being suffocating. It is the formal donut relaxing into the improvisation of the daisy chain.

The phrase daisy chain may suggest a mode of association at odds with the family circle. Sexual slang for a group of more than two partners joined in simultaneous oral or anal intercourse, it acquires in these poems the status of a freak flag emblem flying above the red-light district of sexual and scatological sincerity. Here, the locals discuss freely their genital health concerning “bloodturds,” “comefarts,” and “lucky pierres.” Such naughty talk, derived from the Queen’s English and the Urban Dictionary, provides the ultimate relief and “comfort” from the pressures of having to live up to the expectations of prestige, marriage, and the baby carriage.

Zhang may not plant her booth in the middle of the gay carnival like Margaret Cho, but she seems to chart the same space of intimacy signified by a banner like the fag hag.[6] She poo-poohs, for example, the “avant guard dood … boring me with the cunts” (88), but serves feline or concubine realness in the presence of gay royalty like Marcel Proust or Frank O’Hara: “You were born a queen … and I feel nothing but lucky, lucky to sleep by your feet” (85). By the same token, she channels personism when she writes of an O’Haran intimate: “I’m inside of a daisy chain and the Lucky Pierre is my boyfriend’s penis / inside a whale inside a universe” (76). These queer and dreamy declarations imply that if a woman has little choice but to swim in a literary ocean swarming with men, she may as well surround herself with the ones who make the air and discourse around her easier to breathe.

But why not with the other housewives? Zhang suggests that the immigrant who’s shy and awkward because of her difference has more to learn about social and sexual dignity from the unabashed freak who has come into his own virtues by inhabiting his difference in a particularly fierce way. Conversely, the unabashed freak may favor the immigrant as the ally and informant who shows him the unforeseen corners of his never-never land: “you find me chinky and very fun” (58). In poems like “Philtre,” and “Michael,” the line of hesitation approaches a horizon line of trust between the loveliest of weirdos:

We find you strange

this wire of weird hanging-ass out

the fiery cleavage, the eternal spotlight

of a sunset line of weirdness inside me

weirding out your mother

who was always weirder than my mother

who was as weird as the first chinese person

to say his name was chinga (56)

This daisy chain of a poem features her characteristic coil of a run-on sentence that anchors the speaker to family, yet gives her enough length to move into other cultural communities for the sake of shared enlightenment, to invoke the rope metaphor of Angela Davis.[7] By the end, the Chinese ingenue and the flaming queen bridge the strange gap of their cultural differences via the urban link of Chingy, a black hip hop artist who takes his name from the Chinese. We are told by the poems that “Jenny” and “Michael” are susceptible to cross-referencing each other’s work, and though such coterie gestures will probably mean little to the average reader, they evoke, like the closing dick-and-jane handshake, a larger pattern of collaboration among women and queer men in the avant-garde: “I noticed your thing hanging out” which “we think is a thing between us / and it is in fact so.”

Hallmark moments aside, Zhang recognizes how the respective frames of the donut and the daisy chain collide. Her bitchy mode of political incorrectness often indicates the sincerity the two may nonetheless enjoy in this “simulacrum where you finally had the courage / to tell your mother you love her a lot — / you penisblowing piece of crap!” (66). It is only within this simulacrum that one does not feel obliged to dance around thorny issues for the sake of propriety. The trust that obtains between absolute friends enables the paradox by which they may express the deepest avocations of care and concern in the crassest way imaginable, one that would meet resistance only outside that space of mutual permissiveness.[8]

Pride and punupmanship

The daisy chain also offers an image for the poet’s superb punupmanship. Wordplay, as Zhang sees it, is the embarrassing spittle of the Nabokovian or immigrant soul who bumbles from one corner of the globe to another, screwing up the host language in beautiful and unforeseen ways: “I wanted to refill this charming hole of shame with a sense of happiness and delight … to take these mistakes and make them not mistakes.”[9] So it is that Zhang transforms the linguistic gaffes of her family into willful idiomatic mixups, catachresis, spoonerisms, mondegreens, and the bumbling voice message that furnishes the title of the volume Dear Jenny, We Are All Find. Her daisy chain punupmanship is perky and profane, switching modes between straight and queer contexts, as when she admonishes the friend who chooses a gay hookup over meeting the parents:

this nurse is a sample nurse

this muse is a sample muse

………………………………………

or thoughts of hairy bung-cold lunges

the luncheon was a disaster

as was the plunging of your fisted-anus

into water where it was cool

………………………………………

you take popsicles into your knuckles

like rings attached to doorbells

that wake up my father (57; italics added)

The paranomasian lady who lunches makes the care imaginary yield to both “the children” and the “equation of homoeroticism.” These poems chide and cherish by turns the honorary donut (with his icy, brass-knuckled bravado) who takes a fist up the ass or in the eye for the sake of sexual politics: “you’ve been in an accident? / I will sew your eyeballs back into their sockets,” she reassures him. Gay care provider and seamstress, “nurse” and “muse”: Zhang recognizes the homogeneous donut and the queer daisy chain as equally valid responses to ethnic or sexual discrimination. Her punupmanship across the line break offers an expedient means of attending to the incommensurable aspirations of parties who may frown at one another yet collectively affirm the miracle of her existence.

Poetics of fraternization

Although Zhang specializes in friendship, it would be wrong to zone her within the tradition long in vogue. She does not write about the classical fraternity of equal-footed friends who push each other towards the heights of Olympus at the expense of the natural slaves. Emerson encapsulates the best and worst of this tradition when he states there is no friendship more noble than the “manly furtherance … among … beautiful enemies” and more overrated than the “perfumed amity which celebrates its days of encounter by a frivolous display,” and the friend who is my “unequal shall presently pass away … a mate for frogs and worms.”[10] True rivalry and absolute candor are special privileges we extend to friends who have earned our total respect and for whom “the Deity” inside me annihilates for you “the thick walls of individual character, relation, age, sex, circumstance.”[11] Just not to women, who are too lovey-dovey, frivolous, or housebound; or to the slavish minorities, who stink too much of the bog. In the classic view, only the pearliest of men are perfectly and equally positioned to reap the full benefits package.

No surprise that privilege should blind the superlative rivals of the Emersonian firmament to how the open admission of advantage or vulnerability may sustain friendships more diverse in constitution. In the queer tradition, however, as the scholar Michael Warner reminds us, “the most heterogeneous people are brought into great intimacy by their common experience of being despised and rejected in a world of norms they now recognize as false morality.”[12] Wasps and wannabes dissemble together around their rivalrous acquisition of prestige, while the leveling experience of failure makes the best icebreaker there is for mixed company falling across the thick walls. Flaunting the relationships that society once marked as shameful because they flew in the face of common sense, a figure like the fag hag may discover her potential as an effervescent mascot for the horizon of inclusive relations of care, candor, and commitment falling across delimitations of race, class, gender, age, size, sexual practice, and familial configuration. As Maria Fackler and Nick Salvato write in a collaborative manifesto, the fag hag is a “complex comrade who pushes us beyond the comparatively simple role that sorority may play in upsetting fraternity’s stranglehold on the political imagination of friendship,” one who points us towards a radical vision of democracy still in the making.[13]

The poems of Dear Jenny issue from this space of shared marginality more futuristic in its accommodations of difference than both the chauvinist fraternity house and the sniping sisterhood that once prompted women to reevaluate the feminist potential of the hag. Experience has taught Zhang that certain citizens fraternize with their purported enemies for relief from the matrix of positional suffering as women, as people of color, as sexual minorities, etc.[14] For citizens who are more than one of the above, whose lives are charged by intersectionality, the practice of fraternization may prove more liberating than perfunctory recourse to school chums or the ethnic buddies section. Hope for Zhang means saying sayonara to the hipster gluttons whose street cred ranges no further than the kitchen pantry, but it also means rebuffing the nerdy sister who does little to shake the reputation of the moocow. Dropping from the heights of Olympus, Zhang finds meaningful relief in the friendship of rock bottom:

In the mornings, I slid to the base of the mountain

fulfilled my duties as a rhapsode

denouncing all of Greek culture; “I will not reference

Aeschylus!” I said to my friends who were eating rice

and wearing rice hats and being ignorant of their

ignorant ignorance: “I will bring you the Wu’s, the Lao’s!”

At that point someone banged three pots together

………………………………………………………………………

I shook hands with the bromides, the questionable

youth who came already as an imitation of their future

one had wrinkles around her lips and was tired

of the way society treated her like cattle

“Moooo,” I said

It’s all very scientific and it’s all very necessary

…………………………………………………………………

You and I keep meeting at the bottom

I meet other balls of dust and together we forge a history

later, in meeting new friends, I forget all of this. (13–14)

Such Kafkaesque rants reveal how the admission of failure may ease the sense of rapport that the monster of privilege only seems to discourage. The classroom scene offers a painful window onto the public square where minorities are clapped into silence by those who like to set the loud firecracker against the silently weeping bromide or bovine. When the audience gets away with “eating rice / and wearing rice hats,” the artist is facing a losing battle against the quacksalvers of Orientalism who confuse the harmonious flavor profile with the grittier bottle of authenticity that irritates their stomach. “Being understandable is subject to all kinds of power dynamics and shifting realities,” says Zhang; “When I go to poetry readings, when I meet other poets … so rarely are they nonwhite, so rarely are they immigrants, so rarely are they any of these things … So there’s always that element of I want to be understood … but I also know there are certain limits to communicating past certain power dynamics.”[15]

Zhang attempts to reach a broader audience that remains ignorant about power dynamics by vexing the relations of friendship they pretend to know the most about. The result is that her anecdotes of failed friendship and friendship in failure amount to morality tales on the price of understandability. “How can I be … both damaged and lovable. How do I become the protagonist of a story?” Zhang asks with rare pathos.[16] What can one do to escape the fate of the perpetual sidekick but to change the desiderata for a hero, a savior, a sidekick, a friend?

By invoking the demonstrative idiom of her favorite queens and hags, Zhang breaks the accursed expectation of Old World modesty that conspires to deny the Asian American subject full range and volume in the chattier arts of the New World. With one fist raised towards the sky, she embraces with the other arm the queer playmate whose willingness and willful difference from her person relieves her from the fate of being pushed into a takeout box with the defenseless bovines and running gags. In these poems of fraternization, of friendship with the purported enemy or unforeseen ally, she transforms immigrant bumbling with the buoyant pride of her adopted queen’s throat and burlesque kick, and through the pricklier feelings disclosed by heterogeneity, shows how the structural evils of racism and imperialism place limits on the pursuit of sincerity across the rainbow. Jenny Zhang is kicking proof that the mantle of the avant-garde still belongs to the belated peoples willing to seize it against all odds: she gives us leg and life, launching her fabulous hagship in the face of failure for the benefit of those still yearning from black holes:

… I grab hold of my friends, my people

the ones who woke me when I was sinking

and on the verge of a colossal disappearance

from this flawed and frangible world. (44)

Author’s note: This article for Jacket2 was submitted and edited for publication in July 2015. Any critique of the parties involved in the Best American Poetry scandal will have been by coincidence. — J.N.

1. I wish to thank Jenny Zhang for giving me her blessing to spare the pity and write with pricklier panache.

2. Various postwar avant-garde movements have proven hostile to female participants. The New York School of poets bucked convention to become an avant-garde whose cultural production was organized by the collaborative energies and unabashedly sissy virtues shared by queer-identified artists and sponsors, male and female, heterosexual and homosexual. Such social dynamics help to differentiate the unscripted program of O’Hara and friends from the macho fraternity house ethos underpinning the Beats, San Francisco Renaissance, Black Mountain School, and Black Arts movements. See Maggie Nelson, Women, the New York School, and Other True Abstractions (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2007); Michael Davidson, Guys Like Us: Citing Masculinity in Cold War Poetics (Chicago: University of Chicago, 2004).

3. Jenny Zhang, Hags, ed. Sarah McCarry (New York: Guillotine, 2014), 15.

4. Hags may be said to extend the program first set forth by Mary Daly in Gyn/Ecology: The Metaethics of Radical Feminism (Boston: Beacon Press, 1978): “The Background into which feminist journeying spins is the wild realm of Hags and Crones … Haggard writing is by and for those women who are intractable, willful, wanton, unchaste” (3, 15).

5. See Daly, supra n. 4; and Margaret Cho, I Am the One That I Want (New York: Ballantine, 2002).

6. Some feminists differentiate the fag hag proper from the “woman with gay friends” by the criteria of honorary residency and/or political advocacy within the queer community. See for example Deborah Thompson, “Calling All Fag Hags: From Identity Politics to Identification Politics,” Social Semiotics 14, no. 1 (April 2004): 37–48.

7. Davis invokes the rope trope on several occasions to gesture towards a politics that escapes the tribalist formulations exploited by racists (or naifs) to set people of color against one another: “[R]ace has become an increasingly obsolete way of constructing community because it is based on unchangeable, immutable biological facts in a very pseudo-scientific way … I’m not suggesting that we do not anchor ourselves in our communities. But I think, to use a metaphor, the rope attached to that anchor should be large enough to allow us to move into other communities.” See Angela Davis, “Rope,” New York Times (May 24, 1992): E11. The committed fag hag (of color, such as Margaret Cho) is an exemplary spokesperson whose choice of friends and lovers enacts the intimate cross-racial community that Davis has in mind.

8. For example, see the poems collected and edited by Bryan Borland in Fag Hag: A Scandalous Chapbook of Fabulously-Codependent Poetry (Alexander, AR: Sibling Rivalry Press, 2010).

9. Jenny Zhang, interview by Andy Fitch, The Conversant, May 20, 2013.

10. Emerson, “Friendship,” in Lectures and Essays (New York: Penguin Putnam, 1983), 351, 348, 354. I pick at the Emersonian tradition for the sake of polemic. For a more progressive defense, see Andrew Epstein, Beautiful Enemies: Friendship and Postwar American Poetry (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006). Epstein tries to make the Emersonian tradition of fraternal friendship amenable to racial difference in the token case of Amiri Baraka, though what he calls rivalry seems to blunt the pricklier feelings of envy, irritation, melancholy, and paranoia that register, perhaps, Baraka’s recurring perceptions of inequality within the state of friendship.

11. Emerson, “Friendship,” 343.

12. Michael Warner, The Trouble with Normal: Sex, Politics, and the Ethics of Queer Life (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000), 36.

13. Fackler and Salvato, “Fag Hag: A Theory of Effeminate Enthusiasms,” Discourse 34, no. 1 (Winter 2012): 59–92. See also Derrida, The Politics of Friendship, trans. George Collins (London and New York: Verso, 1997). Fackler and Salvato’s manifesto on the effervescence of the fag hag exemplifies a larger trend in the critical literature on friendship responding to Jacques Derrida’s observation that the philosophical discourse on friendship is ridden by poet-politicians who hijack the benign discourse on fraternity to secure regimes of racism and sexism around the world. We can put Emerson in the same storied company as Aristotle, Montaigne, Nietzsche, Schmitt, and Derrida.

14. Perhaps the mantle of the avant-garde belongs to such subjects in the post-millennium. The free admission of white privilege, argues Timothy Yu, helped to galvanize a more total “ethnicization of the avant-gardes” following the Sixties, when student radicals (who, for example, became the first Language poets) undertook the experiment to reframe whiteness in less toxic and grandiose ways, and as various minority groups (Black, Chicano, Asian, gay, and feminist in constitution) fomented collective aesthetic and political consciousness through the group manifestations of little magazines, ethnic theatre, poetry readings, and protests to organize against patterns of grave social injustice. See Timothy Yu, Race and the Avant-Garde: Experimental and Asian American Poetry since 1965 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2009), 3ff.

15. Laura Wetherington and Jenny Zhang, interview and audio blog post, The Conversant, January 2013.