A poem is a sacred attempt at communicating what is impossible to communicate

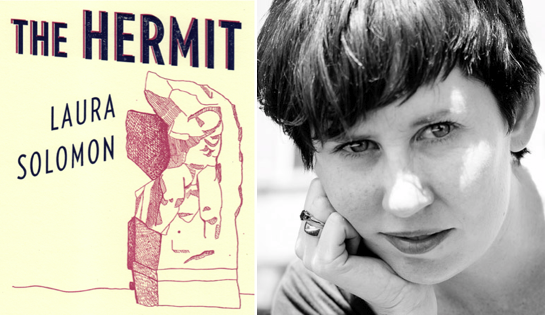

A review of Laura Solomon's 'The Hermit'

The Hermit

The Hermit

“Begin with dreams,” writes Laura Solomon in “Dream Ear, Part III.” The things going on in our dreams are often crazy and impossible, but our dreams are not lies, they are true, physical events going on in our brains and they are entirely untethered to the scientific possibilities of truth in the physical universe. In other words, dreams are a lot like poems. The poems in The Hermit work by allowing us into the strange landscape of emotionally arresting instances of crisis and sadness — lost love, emotional and geographical displacement, fear and anxiety, the wild and absurd sense that time is flying by and staying still. They are gorgeous, daring poems. Reading this book I constantly have the sense that these are poems I would not, myself, have the courage to write because of their openness and generosity; they are uncharted but crystal clear — even as they allude to the world of our dreams, those dreams feel a lot like real life. In “Dream Ear III,” in a dream, on a train, a woman next to the speaker is “sleep-writing”:

a dream is a mirror

that doesn’t belong to you

anymore than words do

after you say them

you forget them but

not always but always

the mirror forgets you

after you leave it

do the words forget too

you after you after you

say them you leave them

with or without a trace

This passage is filled with traces, and traces are questions. What happens to the words after we say them? What truth is there in the illusion that our presence anywhere is indelible? Truth itself is tricky; “it is true, it is true, it is true,” writes Solomon in “French Sentences,” but “sentences are the neediest […] for example, it is true.” It’s a paradox that keeps coming up in The Hermit: words are both so meaningful and so meaningless. Later in “Dream Ear, Part III,” Solomon writes, “in the dream you are becoming / don‘t become just words.” When the words start to feel like they are just words, you run the risk of being full of shit, and to be full of shit is not good if you are trying to communicate. She writes,

you were speaking of a nest I’ve read

with use the nest becomes rimmed and filled with excrement

this serves as a reminder of the humble origins

of all architecture no it doesn’t why are you speaking

of architecture you are full of shit

but it is too late already

you are already forgetting the dream in this poem

you are becoming a dark sooty chimney

with a dark sooty agenda

To be full of shit is to forget that it is sacred to say anything. A poem is a sacred attempt at communicating what is impossible to communicate. The speaker in “Dream Ear, Part III” wants to trim the utterance of all metaphor the way dreams are free from the analyses we graft onto them once we wake up, the way our aspirations (dreams) are free from the problems of possibility.

Because we can’t possibly say how we feel, exactly, and in poems we say how we feel. To have an agenda is to predict rather than experience, to try to see what hasn’t happened yet in retrospect. We might want that privilege, but it doesn’t belong to us. Throughout The Hermit, Solomon gives us the gift of poetry-as-experience so that even though the circumstances are foreign to us, they might feel true. In “Philadelphia,” she writes,

at any rate the only

way it will work will be

if he decides to come to me

then I will know he knows

though I’m not sure

that he’s going to come

all along I guess

I’ve just been wrong

but no I haven’t Dottie

Here we have a poem that feels like a letter, but it unfolds line-by-line, broken and charged with Solomon’s knack for breaking lines so that they move out in all directions, without agendas, a step back once in a while for all the stepping forward. The lines leave traces of themselves that appear and vanish according to the whims of our own experience of reading them. In another poet’s hands, the specificity of “Dottie” might make me feel as though I am not included, but the revelatory quality of Solomon’s progression from line to line makes my experience of “Dottie” feel lived and present. As she writes elsewhere in “Philadelphia,” “protons had to collide in time / to make you you.” The chance encounter of life and time together is the center of the experience of being alive. It’s rare that I pay attention to the fact that I don’t actually know what will happen to me in the next moment of my life; it’s rare that a poem works that way.

Forget though, for a moment, the dreams and the physical laws and think about what you are willing to have revealed to you in a poem. Think about all the times you’ve thought about whether a poem was good or bad, trying to come to some sort of a judgment without ever considering what sort of mood you were in or what sort of experience you were willing to go through. In her essay “Voice” Alice Notley excerpts a short, untitled poem of her own and then explains something about truth and poetry:

Clouds, big ones oh it’s

blowing up wild outside.

Be something for me

this time. Change me,

wind. Change me, rain.

A specific feeling and occasion prompted [this poem], and it still embodies something I can feel; but I wrote it hoping it would be as if spoken by anyone — hoping anyone could “use” it. That is, I know it sounds like me, but while being read it might live inside anyone, being some voice of theirs almost, through sympathy and imagination. But when I wrote it there was a real storm outside.

Reading a poem can allow you to experience sympathy, but you have to be willing to do that. The poems in The Hermit ask a great deal of us. When you come to a line like, “how I’ve wanted to encounter you,” are you willing to take the passage wherever the pronoun takes you, and simultaneously are you touching the poem sympathetically? Who is the you you are thinking of? Where, I mean, are your thoughts? Isn’t this important? Isn’t it great?