Permission to be a poet

A review of Eileen Myles's 'Inferno (A Poet's Novel)'

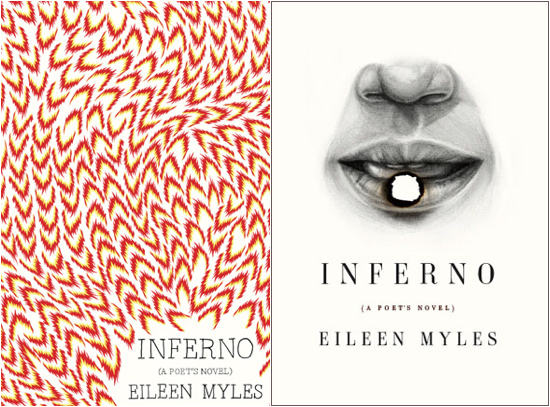

Inferno (A Poet's Novel)

Inferno (A Poet's Novel)

Inferno: A Poet’s Novel begins as a retelling of Eileen Myles’s tough-girl antics in 1970s New York. She plays, at first, a stomping, horny girl-tornado, a lost Dante high-minded enough to keep yammering on about that likeness. In this story she is very broke but good at it. She sells fake subway token slugs, borrows dollars, works in bars, makes rich friends, steals food off trucks. She is our girl hero.

She writes like no one else, often tying the shape of talk to the page with dead accuracy. “Here we go: puking.” “I went to Queens College for a second.” She catches how ambition and attachment circulate through all of us, together:

Sometimes of course I’d walk both dogs. Alice was pretty busy and of course I had the time. And I had competition. There was a grim Marxist-looking woman, a greasy blonde who obviously had a crush on Alice and she took up the slack when I couldn’t help out. The woman was the religious editor at Majority Report, an embarrassing thing in itself. I’d bump into her on the street, with or without dogs, and we’d just glare at each other. Obviously we had the same boss, and the existence of each other simply lowered both of our positions.

Myles is lethal when she’s diagramming how people wish for things, how they use each other, how they operate in time. All these machinations are built of small gears: “What’s that.” “Um, no.” “Of course.” “Uhhh — no.” “Okay. “Okay.”

There’s a ton of good tall tales in this book, which I won’t go into because they are such perfect pleasures. There are brags and brags and brags. There are sex stories that transmit the whole roaring overwhelm, the anxiety of a lover you have to impress, how a lover is always also a guide out of the disaster they will always wreck.

The story of Inferno is that Dante needs direction. Virgil agrees to be his guide and learns him good. In her take, Myles commits to this arrangement totally, and she covers all sides: she shows herself as an innocent asking “Poet, I thee entreat,” she shows that turning to mentors is absolutely necessary (even conceding that mentors often disappoint) and she shows a little of the strangeness of becoming one.

In pursuit of an admired poet (Marge Piercy) at a reading:

I wax professional. I stick my chest out. I know you’re just catching your breath, but can I talk to you for a second. I get a warm gleam. Sort of. But unfocused. Tired. Though she’s probably always like this. I went to U. Mass (Boston) and my professor Eva Nelson was a friend of yours. She’s shaking her head.

Eva — I’m thinking the name sounds kind of wrong. Was that really her name. I forget.

She went to Hunter. Maybe you knew her at Hunter.

I don’t know this person Marge Piercy is telling me. No I don’t know her.

You read —

I have never heard —

Eva Nelson.

No, no she says and now she just wants me to go away.

Other idols she describes open new worlds, or prove haughty and useless, or convince her of her own worth, or take advantage, or literally feed her. In telling the story Myles also positions herself as a mentor and the guidance she offers is serious enough to stay complicated. She argues with anecdote after anecdote that apprenticeship is essential to becoming a poet, but that learning from someone shouldn’t be presumed to be a result of their being any good: “Bad scenes can be essential. The world was coughing up information in record time. I used all of it.”

That we finally reach the section “Heaven” — bragging on having finally got there— is important because Myles admits herself into the company of idols who can fall flat and be wrong. With that caveat implied, she does offer advice as an expert that left me grateful, not annoyed. It’s advice that stands out against a lot of the advised ways of being a poet in 2011. What worked for Myles was a balls-to-the-wall, all-in kind of hunger.

The character [in Hamsun’s Hunger] was going to starve, unless he made money on his art. Which was basically my ideal. Nobody ever told me how to live, they told me what not to do. In all these books about the lives of artists that I read I mean they weren’t guidebooks but they took the simple beliefs in art and freedom and carried them to outrageous lengths. I could do that.

This lesson is implicitly generous. As is her appreciation for how long apprenticeship continues — part of the book is written as a grant “Submitted by Eileen Myles to the Ferdinand Foundation,” a joke on how long you trudge along asking, “Am I there yet?” Myles seems to offer, with some tenderness, that the question “Am I there yet?” is a good companion. It keeps you honest.

In Inferno, Eileen Myles lays out lots of gifts. Between the sharp humor and the impossibly clean lines she gets a little corny. Mainly she is giving permission: permission to be a poet, in a dated, romantic, full sense of the word. And permission to find new ways of doing that, whatever you need, and permission to be dissatisfied, to continually want to do it better.