On the outskirts?

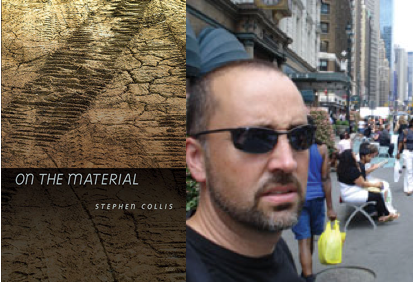

A review of Stephen Collis's 'On the Material'

On the Material

On the Material

For some years now, Stephen Collis has been working on a grand plan, a mission even — a plan toward which the volume under review, On the Material, apparently plays little part. Collis’s last two volumes of poetry, The Commons (2008) and Anarchive (2005) were contributions to what he has called The Barricades Project, an amorphous work-in-progress originally envisioned as including maybe three or four books of poetry and a novel, but now increasingly expansive and (the same thing?) ambitious. (For more details of the genesis and ongoing metamorphosis of The Barricades Project, see The Poetic Front, the online poetics journal Collis edits. He currently sees the pre-existing volumes as part of an initial section, “Platform,” while a second section, “The Architecture,” waits in the wings.) The focus of these first two volumes, and what they tell us of the scope of Collis’s project, is instructive.

Anarchive takes as its explicit subject matter the Spanish Civil War, but draws a lot of tangential material into its gravitational field: the anarchist thoughts (and deeds) of Kropotkin and Bakunin; Durutti and Ferrer; the Picasso of Guernica; Buňuel; Robert Motherwell; Lorca; Lorca as interpreted by Jack Spicer; the apocryphal Ramon Fernandez of Stevens’s “The Idea of Order at Key West” (rather than, or maybe in sync with, the real life critic); and, last but not least, Joe Strummer and the Clash (via “Spanish Bombs”). Despite the punning title and the self-depreciating self-depiction of himself “pulling down texts,” what is most striking about the volume is Collis’s continual passion and engagement: this is not backward-looking historicism for him, not an academic exercise; these are not dead battles:

I produce what is past

again and again

our souls slumped against

the desk whispering

throw it down

throw it down

at the heart of the future

repetition

this hope this elegy

espero elegio

that the violence of forgetting

will be remembered

with indignation

and a correspondence

over Spain will be

the always of revolutions

(There’s even room for a good bad joke: “and you called it paltry / when I spoke only of chicken”).

This powerful sense of empathetic engagement is carried over to The Commons, where the focus is now on the romanticism of Wordsworth, Clare and (via a quick transatlantic leap) Frost and Thoreau, the disputed reality of enclosure and landownership underlying their supposedly neutral “landscapes,” and the ideal of “wandering” as political act. Collis fervently disagrees with Frost’s neighbor that “good fences make good neighbors;” “The Frostworks,” the first sequence in the book, is a commentary on/palinode against Frost’s “Mending Wall,” and sets the agenda by preferring commonality over separation:

something there is

isn’t just

yours or mine

but between

the light of

eerie dawn or

dusk I coat

the fresh rockery

with movements

and maybe

stone fish fibre

crack block breath

bends leans turns

this onto that

in structure

I’m leaning

Into you too

Collis sets revolting peasants, Levellers and Diggers against enclosure, John Clare’s solitary journeying against confinement, a variety of period tourist guides to the Lake District against Wordsworth’s monolithic vision, all the time stressing freedom and variety over restriction and dearth: “O fence us not to fringe our senses” vs. “enclosure came / to dampen rambles.”

The aim of both books is seemingly to render a lost historical moment tangible again, for the grain of unused potentiality buried in the strata. Borrowing an epigraph from Frederic Jameson — “History progresses by failure rather than success” — Collis casts this belated quarrying piercingly:

What is history but the record

of the places where we were broken?

The triumph of these books, however, is that they refuse to see this situation as merely hopeless:

the wall

between us

is a collapse

of constituency

the boulders

are loaves

we break

together

all is pine

or apple trees

only he says

with nothing

between us

how are we

yet broken

In contrast with such ambitions, On the Material is “just” a book of poems. It is, in fact, the most disparate full-length volume Collis has produced thus far (even his debut, Mine, was unified in the attention it paid to the mining history of Vancouver Island). Given that The Barricades Project is, in prospect at least (and contra Pound), a poem containing everything, what does it mean to designate On the Material as outside the work? Is it even possible for there to be an outside? One of the most obvious differences, although it yields to complications on closer inspection, is that, coming from a poet more usually concerned with the epic (or, at least, the semi-epic, or post-epic), On the Material offers a relatively joyful (though occasionally sorrowful) romp in the fields of the lyric.

The first section, “4 X 4,” is the most contained and immediately engaging and attractive. Made up of forty-four sixteen-line poems, each organized into four-line stanzas (4 x 4), topped and tailed by a “double” intro and outro of eight four-line stanzas, making for a grand total of (48 x 4) 192 stanzas and 768 lines, it is shapely and orderly despite its locally disjunctive syntax. Such order both does and does not fit the subject matter. The sequence recounts a period “between February and May 2008, while travelling (or in anticipation or the immediate aftermath of travelling) in Vancouver, Victoria, Calgary, Toronto, Buffalo, Portland, Anaheim, and San Diego,” the planning beforehand and the retrospection afterward. Place tends to bleed into place, and the titular vehicle becomes the defining constant. It all makes for thrilling contrast: as with all true satire, it flirts to some extent with the thing it professes to hate, and Collis does a good job invoking the sublime joy of the automotive:

Looking out the window I will

SUV all over this tarmac world

Fogs lights on suburban gladiator grill

Crunch of rock under tire

Whenever such elevated perspectives induce dreams of hubristic, panoptic power, the poem rights itself with playful bathos:

Here is a claw I

Took from a crab and now

Pretend to pinch at people with

Allegorical delight

Indeed, “4x4” and this volume as a whole allow Collis to stray away from the history of the Barricades volumes into genres (lyric, elegy, satire) and contexts (contemporary landscapes both tangible and geopolitical) previously alien to, or on the margins of, his poetry. In fact, it is somewhat shocking to encounter Collis so resolutely in the “now”:

We were in the last days of the

Poem sun glinting off countless new and identical

Condo towers hard and the warmth of

Gourmet coffee car idling at the curb

References to “Dubai indoor skiing,” “Hotel Europa,” “Ikea,” “Rumsfeld insisting insurgents / No longer be called ‘insurgents,’” “my Google brethren” and “the vast salt deserts of the Americas” abound, showing Collis’s mind out beyond his immediate physical peripheries, roaming the biosphere.

“4x4” ends stalled — as all satire must? — in “the desert of desire,” with a mere Utopian glance at a possible “ark of resistance” as “horizons future-lit burst bright beyond the frame.” Fun and games continue in the book’s second section, the Sonny Curtis, Bobby Fuller and Clash-echoing “I Fought the Lyric and the Lyric Won.” Collis has long rewired the lyric to carry epic-heavy freight, but has he been explicitly antilyric in the process? Well, if a prominent, foregrounded and consistent “I” is the lynchpin of “lyric” poetry, then that has never been the primary concern of Collis’s history-centric work, even if it has never directly denied the subjective: he simply wasn’t there personally and — as the “Dear Common” sequence shows — The Barricades Project keeps floating the possibility of the communal instead, of a subsuming of the lone ego in the mass.

Equipped, then, with a newly defined, individuated ego, the poems in “I Fought the Lyric and the Lyric Won” ring the changes on a whole gamut of recognizable lyric forms — the death haunted nature-inspired epiphany (“The End of Flight”); the modern(ist) twist on the classical (“Aristeus Mourning the Loss of his Bees”); the ode (“The History of Plastic” — more than ambivalent, admittedly); the intertextual conceit (“Self-Portrait in a Corvette’s Mirror”); and, last but not least, the ekphrastic ars poetica (“Poem Beginning with the Title of a Cy Twombly Painting”) — all given a Collis-specific spin (a natural-epiphany poem in Zukofskian five-word quantitative lines? A bee-filled Virgilian pastoral complete with cell phones, emptied accounts and spy cameras?). In its lack of a single unifying theme or approach, this section may seem the slightest of the three in the book, but that overlooks (or undervalues) the considerable wit on display and the degree to which these poems, precisely because of their “outsider” status, throw up microcosmic metonyms for Collis’s whole project, sometimes plaintive:

Is making itself

the problem?

Sometimes strident:

This means build I think

The architectures of dream the

Streaming columns rooms of gold

With poetry walls all jade

And gleaming and dark with

Night and wanting the firey

Posts shining lintel and above

This I’ll hang a flaming

Bird and its eternal flight

Will take whatever I have

Built with it

The book’s third and final section, “Gail’s Books,” carries Collis’s newly established lyric perspective further into the realm of elegy. The introduction relates how, shortly after the 2002 death of Collis’s sister from cancer, a fire destroyed her house, taking with it her worldly possessions, including her library, with the exception of only a few books: Kathleen Raine’s Selected Poems, Rilke’s Book of Hours and Novalis’ Philosophical Writings among them. With poetry presented as the “hinge” where the siblings’ interests met, it is not surprising that Collis seizes on the textual as a possible bridge between his own materialist perspective and the mystical and spiritual concerns that gave his sister what he calls an “outsideness to time.” The section takes it epigraph from Michael Palmer — “There’s still no truth in making sense” — and many of the poems seek to reverse the phrase’s logic, wringing some kind of hidden truth out of near-nonsense. The sequence “Variations and Translations from Rilke’s Book of Hours,” for example, translates not only homophonically (leading to such splendid right-wrong titles as “The Night Dies Sick and Stunned, Its Root Mic On” and “Ditch Water Nixed my Steam Watch”) but also “from one English to another,” yielding depth-sounding counterfactuals:

Swell, eye, to end times

Mic a bee whispering

“Lover of sheaves,” night

And waking feel the stream

Oven on, it’s cooking books

A stream wants moss

A rung lower, and tongs

Everywhere, Gail’s present absence is palpable. This is the burden of elegy, and, unsurprisingly, it draws from Collis some of his most tender and hushed writing to date:

Who speaks in limits is smoke

Whose hand opens the book points threads

Whose sister is the fire forming smoke

Whose ash is now ash’s ash

Who walks in that tall flame smoked

A politics rests its hands on its knees

A bird is in one hand it is

a flicker

The final (and title) poem links this individual loss back to Collis’s overarching rationale for poetry:

Though long dead

they reach you

with lines more

material than you

could have imagined

stays and spars

holding your vessel

in place

Whatever the individual attractions of the poems in On the Material (and they are, as I’ve hopefully indicated, numerous), as a whole it drives this reader at least to more general questions of inclusion vs. exclusion and the role of the “long poem” (or, even more dangerously, the “epic”) in early twenty-first century poetry. Is On the Material mere “parergon,” fingerwork warming up for the next bout of Barricades-related poetry? That belies the emotional heft of “Gail’s Books” and the satiric energy of “4X4”. There are things here, emotions and techniques, that, so far, Collis has not included in his longer work. One suspects the vacillation itself — is this out or in? — to be creative, a sort of built-in irritation out of which (does the oyster want the pearl?) further poetry will grow. The juxtaposition generates its own effect: this is Collis’s most personal volume to date, but, due its place alongside his other ongoing work, it never feels blandly confessional, rather just one more avenue of possibility.

The attraction of “The Barricades Project” as title, as concept, as riff on Benjamin’s Arcades Project, is in the translatability of raw material, the cobblestones that allow for swift transportation transfigured into defenses and obstacles that thwart access. Move them from one street to another, wherever the fighting is. Collis, as poet, unsurprisingly sees such flexibility and use in words themselves:

Try a “Barricades Project.” It can be made of words — it (power/revolution) always is. Tear them out of text and put them up against the sky, across the street.

Collis writes of the lifepoem, the work like Wordsworth’s The Recluse or Pound’s Cantos so tied to the poet’s life that death alone provides (artificial) closure. What does it mean, now, to adopt such a model self-consciously? Can one plan a ruin? Collis, quite likely, would assert that matter dictates the matter and that his expediencies and plans are as nothing compared to his whims and the necessities of his project (remember Pollock: “I am nature”):

It’s not that I advocate errantry

It’s that movement says rive

So, is On the Materials in or out? If you say so.