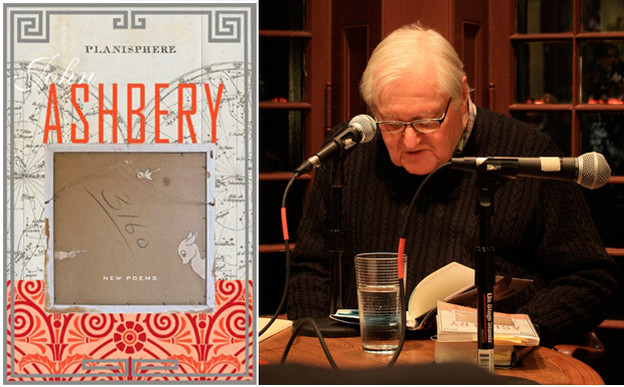

Ongoing 'Planisphere' notebook

Planisphere

Planisphere

1.

People are much too free with the phrase “a great book of poetry.” They think if the book has ten really good pieces in it then it’s a great book.

They don’t talk that way about albums. For it to be a great album it can’t just have some hits. You have to consider the not-hits, too. I wanna say: If you simply skip over the not-hits with no regret whatsoever, you can’t really call it a great album.

Berryman’s 77 Dream Songs has twenty, maybe thirty jewels. Plenty of the not-jewels are more or less unintelligible. Yet you regret skipping them. Somehow they contribute something to the overall presentation; you never wish ’em away. Shakespeare’s sonnets — same thing. Heaven knows one does pick up these books and skip to the best stuff. But one regrets it.

Now compare all that with, for example, Yeats’s The Tower. There, you have plenty of hits, but you skip over the other stuff quite, quite gladly. It’s boring. You have to assign the not-hits to yourself like homework. I do, anyway. Planisphere, meanwhile, is almost exactly the reverse. The hits are in rather short supply — but you really do wish you could take in the whole thing, every time you read any of it.

Trying to pick out anthology pieces from Planisphere would be like trying to take excerpts from a CD of whale songs. You don’t put that stuff on for five minutes.

And actually, you could say this is a large part of the nerviness of Ashbery’s work. He has dared — for fifty years — to be supremely unportable.

2.

On the other hand, if an editor were prepared to concoct an Ashbery “Selected” in total defiance of any and all expectations — principally the expectation that such a collection ought to contain {pieces representative of the poet’s oeuvre as a whole} + {a more or less even distribution of poems, starting with Some Trees and ending with Planisphere} — if, I say, an editor could forget about all that, he or she could deliver an Ashbery hitherto unsuspected by his detractors, and, to a lesser extent, unsuspected by his admirers.

A fine samizdat project for some enterprising young citizen.

(I recommend including “The Youth’s Magic Horn” from Hotel Lautréamont, and “… By An Earthquake” from Can You Hear, Bird. From Planisphere: “Default Mode.”)

3.

Actually, now that I think of it, another way in which Ashbery is quite portable is on the level of the individual line or ‘bit.’ Nothing easier than to gather neat buttons at the button store. Here’s a grab bag:

I’m barely twenty-six, have been on Oprah

and such. (2)

Call me potatoes and soap.

Call me soap and potatoes. (10)

They were living in America further gone into teats. (17)

Ow. In fact ouch. (44)

Refusing to admit

something is the matter with you is like taking

a life. There are no witnesses. (46)

You say your cunning comportment

is artless? Well then so am I

for containing you, champ. (54)

A love like self-love

upgraded to “pastoral.” (68)

Alongside, something was running.

It had a note in its maw. Hey,

give me that, like a good animal.

That’s fine. Now get lost. (89)

[…] and the boy stands at attention, distracted,

in the sexual chapel surrounded

by correct, cream-colored leaves. (92)

The playoffs — don’t get upset. (96)

He was a very mobile person throughout his life,

instrumental in helping promote the Indians. (98)

What about poisonous sea snakes?

I know one. I bet you do. (107)

Then it’s back to basics, or in

my case forensics. What doesn’t

dapple you makes you strong. (107)

Or ask Leporello. (107)

It was time to drink,

and drink they did until the heavens reopened

and the stars were raked into a pile. (115)

Why what a lovely day/street/

blank canvas/pause/orb/

old person/new song/milestone/

caned seat this is! (119)

So we’ll go no more a-teething. (125)

Claymation is so over. (130)

Here as I have erected

to do is a baseball bat. (132)

It wasn’t meant to stand for what it stood for.

Only a pup tent could do that. (133)

If tact is a mortal sin

we shall not miss. (135)

The above nosegay was not created casually. Those twenty-one items were culled from a batch more than three times that length: a comprehensive transcript of all the passages that are neatly underlined in light green ink, in my copy of Planisphere.

Anyone who has read the book is bound to view the above selection with a pleasant combination of recognition and bewilderment. Anyway, about half the time R. reads me choice bits out of his copy, I think Ah?? Now how did that get by me?

After all, though, it’s not too hard to figure that one out. Book’s a forest litter.

4. Some common objectings to Ashbery — answered

OBJECTIONS

(a) Doesn’t all this allegory and code on the subject of poetry-writing itself get a bit wearisome after a while? I mean, it’s not like he’s saying anything bold. And it’s every other poem.

(b) The persona of this book — gentle, quirky, finicky, likable, 100% harmless in every way — don’t you ever get sick of the coyness of all that, the self-satisfaction?

(c) Aren’t seventy or eighty percent of these diction oddities just a bunch of honors-dorm humor?

A stupor like sheep’s nostrils

chases the ground. Day arrives with a thwack

and is left to sit all day. (129)

I’ll have a mustard coke. (134)

— and so on. —

ANSWERS

(a) When people object to poetry about poetry, it’s usually because they don’t like the specific attitude being struck. Anyhow, in my experience, the same readers who reject Ashbery’s devotion to writing about poetrywriting never seem to mind it when, say, Hafez or Han Shan relentlessly handle the exact same theme. The difference is that those two guys never do anything but vaunt poetry’s powers. Meanwhile, Ashbery is a relentless skeptic, both of the art in general and of his own stuff in particular. Which is the very reason he is attractive to some readers.

(b) Is Ashbery coy and self-satisfied? Take the case of Ashbery’s references (supposedly much multiplied since Flow Chart, 1990) to his own can’t-be-very-far-off death. Ashbery always handles the theme in exactly the same tonal register:

I guess I must be going. (2)

Now it was time, and there was nothing for it (6)

Don’t forget to write! (64)

I was halfway out the door anyway (70)

There is nothing like putting off a journey (75)

Yet one says, so long (81)

I’ll be on my way (99)

I have to go (108)

Well I can’t stay (129)

We’re moving today (130)

We’d better be getting along before it gets dark (135)

Soon it was time to choose another climate (139)

Now, obviously the tone here is appealing. Modest, inoffensive, quotidian — and above all, reconciled. (He even has a poem here that begins, “As virtuous men float mildly away. …”) And the question isn’t even whether all this is a sham or not. It’s whether there’s an unseemly self-amusement/self-satisfaction evident.

Say it is a sham. A fantasy of going gently into that good night. As fantasies go, it’s not ignoble. The poet is led away to the common slaughter, his eyes wide open, his mind somewhat fuddled, his mouth full of neither fulsome blessings nor thrilling curses. He says merely Bye now! and Que sais-je?

Sounds like as good a way to go as any. The obnoxious thing would be if Ashbery were rubbing that ideal up the reader’s snout. Certain people can’t help but take it that way, depending on how strongly they think it’s the wrong fantasy. If your aesthetics of deathbed speeches calls for Shakespearean oratory (of one form or another) or zoinks of Zen cold fusion, then you’re bound to feel like Ashbery’s trying to score a point off ol’ Shakespeare or whatever.

In other words: “self-satisfied”? Sure, if you like. But if you say the li’l guy routine is a smarmy put-on, I say unto you: Examine your conscience. I bet your objection is more to li’l guys than to put-ons and smarm.

(c) Diction oddities and honors-dorm humor. Now, here I’m happy to admit Ashbery’s sense of fun does not do it for me, a whoppin’ percent of the time. Phrases like “mandrills on the turnpike” leave me cold, cold. But there is a very great difference between being left cold and being provoked to the kind of rage represented by a certain familiar illustration from Through the Looking-Glass.

That’s how I used to react.

What made me change? That’s easy. I stopped thinking Ashbery was grinding an axe with that stuff. Making a point. Mocking expectations. Being deliberately lame. These days, I just figure he thinks all that stuff is swell, and I calmly disagree.

I still have Tweedledum-style meltdowns from time to time, but latterly I reserve that kind of thing for situations where I have to listen to the dorks defending the yaks and the thwacks and the mustard cokes by recourse to high-sounding words and philosophy.

(This is actually a deep point about misplaced dislikes of Ashbery. Gotta take care not to hate him when you should be hating the people who smack their silly lips over the worst parts of him.)

5.

TWO BITS:

(a)

Pol. What is the matter my Lord.

Ham. Betweene who.

Pol. I meane the matter you reade my Lord.

Ham. Slaunders sir; for the satericall rogue sayes here, that old men haue gray beards, that their faces are wrinckled, their eyes purging thick Amber, & plumtree gum, & that they haue a plentifull lacke of wit, together with most weake hams, all which sir though I most powerfully and potentlie belieue, yet I hold it not honesty to haue it thus set downe, for your selfe sir shall growe old as I am: if like a Crab you could goe backward.

(b)

MRS TEASDALE: I’ve sponsored your appointment because I feel you are the most able statesman in all Freedonia.

FIREFLY: Well, that covers a lot of ground. Say, you cover a lot of ground yourself. You’d better beat it. I hear they’re gonna tear you down and put up an office building where you’re standing. You can leave in a taxi. If you can’t leave in a taxi you can leave in a huff. If that’s too soon, you can leave in a minute and a huff. You know you haven’t stopped talking since I came here? You must have been vaccinated with a phonograph needle.

These are samples of bewildering nonsense. Which is not to say there isn’t any sense there. In fact, it’s almost all sense. It’s just strange.

What exactly would have to be left out from those bits to make ’em into Ashbery poems? And what would need to be added? I feel like if I could put my finger on that, I’d really have something.

I think most of what stops the Hamlet and Groucho bits from being Ashbery poems is the jiu-jitsu aspect. In both cases, an affront is being prosecuted, quite single-mindedly. Ashbery would never do that. He only allows bitchiness or obnoxiousness to show their heads for half a second.

You know something?

I don’t care. (12)

— and the like.

But even if we leave out the aggressive energy, the Groucho/Hamlet things still have too much forward momentum to count as Ashberian. Their logic doesn’t zigzag any old way; rather, it spirals upward and comes to a point, like a sundae with its cherry. The cherry is not ice cream; crabs have nothing to do with it; where did that phonograph needle come from — and there you are. It’s the “and there you are” effect that makes Hamlet or Groucho quite distinct from the author of Planisphere.

Ah. To make a poem that might pass for genuine Ashbery, you have to create speed without momentum. The associations have to move as rapidly as they do in the material quoted above, but they can’t seem to be tumbling downhill. You can have an exciting ending, but it has to come out of nowhere. Or seem to.

Naturally, the above principle is violated occasionally by the master himself. But when he does so, he produces a poem that would never win a Pass-Yourself-Off-As-Ashbery Contest. Wouldn’t even make semifinals.

(Young poets should take heed. For many and many a magazine does indeed operate almost exactly like a Pass-Yourself-Off-As-Ashbery Contest.)

6.

Occurs to me to mention: people need to stop talking about Ashbery’s poetry like it mimics the way people think. I mean, I guess it does, in a sense. But.

Here, look at this famous thing out of Hobbes:

For in a Discourse of our present civill warre, what could seem more impertinent, than to ask (as one did) what was the value of a Roman Penny? Yet the Cohærence to me was manifest enough. For the Thought of the warre, introduced the Thought of delivering up the King to his Enemies; The Thought of that, brought in the Thought of the delivering up of Christ; and that again the Thought of the 30 pence, which was the price of that treason: and thence easily followed that malicious question; and all this in a moment of time; for Thought is quick.

In that sense, yes. Ashbery mimics the flow of, etc. But real free associations don’t have anywhere near the kind of verbal body that the poems in Planisphere have. When one is ambling through one’s day, washing dishes, unloading the car, one’s thoughts are like a muddy river on which a few twigs and sticks are being pulled along. Those are words and phrases. The river itself is something else again. If one were to translate the whole river into language, it would look like nothing you’ve ever seen before. It certainly wouldn’t look like a Planisphere poem.

I say this with some heat because I have heard Ashbery explained ten billion times in terms implying that the justification for his procedures lies in the way they reveal something about how consciousness operates. As if that’s why he’s good! But how uninteresting Ashbery would be if his explainers were right about him. To me, the exhilaration of the thing is not that it mimics the flow of consciousness; it does something much better. It mimics the flow of a superhuman consciousness.

This is the thing it has in common with the Hamlet and the Groucho bits. Nobody could make all that stuff up at that speed in real time. If a person pulls it off to the depth of twenty seconds, he or she is said to be in rare form, “on a roll,” and so on. You wanna run off and write down what they said.

7.

The speed of the associations is its own thing. It doesn’t need defending under color of mimesis. But there is one thing about Ashbery’s poems that really is wonderfully mimetic of ordinary mental operations. The strong — and indeed unignorable — presence of banality. Ashbery has found a hundred good uses for that.

I’m reminded of Auden on the subject of Boswell’s journals:

When we read Rousseau or Stendhal or Gide, we are conscious of artful highlights and shadows, and keep asking ourselves, “Now, just what was his secret motive for confessing this or recalling that?” But when we read Boswell, the character presented is as complete and transparent as a character in a novel by Defoe or Dickens; we cannot imagine there being any more to know than we are told.

Take for example, the following extract:

When I got home, I was shocked to think I had been intimately united with a low, abandoned, perjured, pilfering creature. I determined to do so no more; but if the Cyprian fury should seize me, to participate my amorous flame with a genteel girl.

An ego-conscious writer like Stendhal would never have allowed himself to write phrases like “the Cyprian fury” or “my amorous flame”; he would have reflected, “These are clichés. Clichés are dishonest. I must put down exactly what I mean in plain words.” But he would have been mistaken, for everyone’s self, including Stendhal’s, does think in clichés and euphemisms […].

Auden’s defense of cliché is limited to its deployment in self-portraiture: diaries and the like. He prizes it as evidence of honesty, authenticity. But that’s not what I’m saying about Ashbery. I’m saying Ashbery’s insistent use of phrases like “I kind of liked it, though” and “it was so nice outside” represents THE thing his poems have in common with normal thought. NOT the speed of association.

When it comes to speed, the poems are analogous to thought. The banality, on the other hand, is the thing itself.

A previous version of this piece first appeared in January 2010 on Digital Emunction (now defunct).