One foot in the real, one wing in the ether

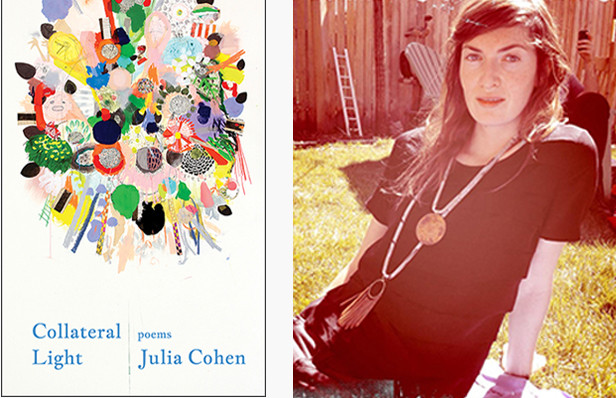

A review of Julia Cohen's 'Collateral Light'

Collateral Light

Collateral Light

“I believe only in the evidence of what stirs my marrow,” Antonin Artaud writes in his “Manifesto in a Clear Language.” “I am visceral!” cries Julia Cohen in Collateral Light. There is evidence to believe it. To engage with this book is to be involved in the marrow-stirring process. To be plunged, arrow-like, into the breathing body and to pass clear through the bloody flank to the still, white bone. And yet, despite the violence of this tragically un-vegan metaphor, the hand that lifts us from the quiver is gentle, and generous, and shrewd, and funny. The arrow’s destination remains, somewhat miraculously, whole and unharmed. By Cohen’s hand, we sail through the air, through the delightful estrangement of seeing the world transform into a sea of tiny objects below us, and when we land, we’re deeper inside of our own guts than we thought possible.

The arrow is a metaphor I didn’t choose. Cohen chose it, again and again, as one of several images that arcs through the collection, threading the presence of a single idea through what is otherwise a book virtuosic in its endlessly renewable imagination. “No One Told Me I Was the Arrow,” the opening poem of the book’s first section, introduces the sharp, flying object:

I raised

a black rooster

tipping

the color

of my red

heart’s name

I sharpen

my point

plunge

into a glass

of soil

The images here are representative of Cohen’s overall approach to imagery, in that they are attentive and surreal. They are compelled to be precise — “a black rooster” — while at the same time mostly unstapled from the rules that govern our particular physical reality — “tipping / the color / of my red / heart’s name.” They are at once preoccupied with the limitations and ecstasies of being a being, and soaring beyond the meatbody. “My pixels / deflect arrows.” Cohen’s is an imagination with one foot in the real and one wing in the ether.

As Artaud’s brief “Manifesto” continues, he too invokes a sharp weapon, this time as a means of getting at a theory of the image:

There is a knife which I do not forget. But it is a knife which is halfway into dreams, which I keep inside myself, which I do not allow to come to the frontier of the lucid senses. That which belongs to the realm of the image is irreducible by reason and must remain within the image or be annihilated. Nevertheless, there is a reason in images, there are images which are clearer in the world of image-filled vitality.

Artaud’s knife and Cohen’s arrow — and, by extension, Cohen’s imagery — are to be understood in context. That which is irreducible celebrates the capability of the image, and Collateral Light is nothing if not irreducible. “Color has me / I imagine,” she writes in “The Place We Worry About,” one poem of many thatembodies the image’s power to evoke real feeling by lifting real objects from their realist circumstance and refashioning them, collage-like, into a new and essential unit. And as in so many of Cohen’s poems, this careful curation of unlikely language-objects yields, as discovery does, a complex mix of anxiety and delight:

Plastic analysis

of a house rhythmically

in gardens

To shuck the silken

**

An accent misplaced

Slackness of violets

In opposition to the place we worry

As evidence effects the afternoon

How real the object

remains despite all abstractions

A violet rash

Denied their easy and expected environments, our senses perk up. They worry. They anticipate. Without the bright light of narrative, we feel around by the glow of our heightened senses, encounter each object one at a time — gardens, silk, violets — and our relation to them is necessarily instinctive, from the gut.

Indeed, the theory and execution of “feeling” is a constant conscience in this collection. “I can’t just sit here with feelings,” Cohen writes. “I wear / the frame of the glasses without glass / so you can touch my eyes.” Here, even expressions of tenderness are rooted in a visceral, penetrating strangeness: “I put my face / inside your face // & look down / at the sunken garden // My toes are cute // My packet of / bees comes in.” It’s the old joke about how the best way to someone’s heart is through his chest, with an axe. A knife, an arrow. Cohen’s images sharpen and plunge, and stay in us.

But I want to give you a new feeling one you can’t

get rid of right away

That the arrow represents a pattern in the collection is indicative of the collection’s generosity, its interest in collaborating with the reader as she makes exploration through the book. Cohen intuits our biological need for patterns even in the most imaginative of playgrounds and creates structures for the rational brain to play in, while at the same time challenging it to play differently. Often, we find Cohen establishing small moments of certainty and then destabilizing them, urging our rational parts to recognize themselves and nonetheless look to the gut for guidance, as in these lines from “Someday You’ll Be Replaced by Language & Then Nothing at All”:

I killed the beast & then I became the beast

Whatever I ask for turns red

watery

I climbed the stairs before the staircase

I’m to blame

Your first image bounced back the real ear

sits in the chest

To bend our biology toward “the real ear” requires that we be convinced by the power of the image to speak, and the legitimacy of the gut as a source of listening, of feeling, and, ultimately, of truth. It requires that we add the rhetoric of knives and arrows, their sharpness and irreducibility, to our definition of what is to be believed. (Who will argue with an arrow when it’s lodged in the skin?) These poems embody the sense that the particularity of the visceral, of our physical biology, cannot be separated from the instinctive, mysterious quality that also resides there. “Abdomen domain // Where I store my arrows.” The same is true of our feelings — driven by pattern and information, characterized by outburst. As it explores these capacities in the image and in ourselves, Collateral Light curates a feeling of what poetry — and what we — might be capable of stirring.