Method for facing a chaotic and threatening world

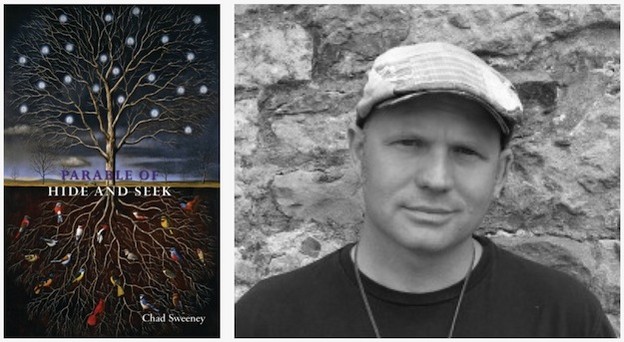

A review of Chad Sweeney's 'Parable of Hide and Seek'

Parable of Hide and Seek

Parable of Hide and Seek

In Parable of Hide and Seek, Chad Sweeney offers highly allusive and sonically textured lyrics that bring the reader to the edge of darkness, but always with a wink, the sense of menace tempered by the taut music of the pun. “Diurne,” the book’s first poem, gives us clues to the ways Sweeney’s rigorous imagination works. Here, he conflates time and frequency, subverts the ordinary much as Chagall subverts the laws of gravity: “I listen to my heartbeat / on the radio, 89.6 A.M.” Whimsical distortions continue as the speaker tells us he hears his heartbeat as “a prolapse then a whimper.” With a bow to Eliot’s “This is the way the world ends / “Not with a bang but a whimper,” Sweeney warns us — whimsy is deceptive. The day (“Diurne”) is dark. “It’s fear and something else — / black milk,” and we can’t help but taste “Black Milk of morning,” the visceral refrain of Paul Celan’s Holocaust masterpiece, “Death Fugue.” What follows, “static from a sermon,” initially seems a pun, but becomes charged when the reader questions whether “static” implies irritating noise, or lack of progress. Here, as in many of the poems in this collection, Sweeney plays hide and seek with clues as opaque as Malevich’s painting, “Black Square,” the poet’s method made clear in “Captain’s Log”: “The only art / is the opaque art / of surfaces.” In the final tercet of “Diurne,” the reader is pulled back to the initial image:

… a feeling of dread.

In the memory of that day

I can’t keep the wind in its box.

Sweeney’s speaker must release that mouthful of air to convey his concerns.

“Diurne” serves as an entry into Sweeney’s large themes: What are the possibilities for a self, a society, a world? What does history tell us about restriction, oppression, annihilation? Life is fragile — “the ribs of the tiger are rippling” (“The Piano Teacher”).

In “The Factory” workers build cages with careful preparation: “Each cage has a unique serial number.” As Sweeney explores restriction, the kinds of imprisonment humans have imposed on self and others, surreal details accrue:

We refrigerate each cage for one month.

We bury it in lime.

We sleep three nights inside each cage.

We hang it from the eaves.

Work numbs where only “once an hour the sun was caught inside our cage. / I swear it, the colors changed, / wind paused for the outcome.” While sun signals freedom, the freedom is transitory. The speaker reminds us that numbing happens so slowly, we’re unaware it’s happening: “It takes one year to grow a cage … / Long enough to teach a child / to weave a clothing from the keys,” something to protect the child from cages he or she will endure — perhaps in school (Paul Goodman’s notion of miseducation) or at work (the shuffling Chaplin in Modern Times, a hapless cog in the machine). The speaker suggests keys to unlock the cages:

One key is a rib.

One key is a cypress.

One key is a hammer.

One key is a sound.

Here again, we puzzle over Sweeney’s koans: Does rib as key refer to Eve, to a rib used to support a structure, or to the rib a potter uses to shape and smooth a vessel? And surely it’s the rib in our own rib cage, and the rib/the joke’s on us. We soon discover the speaker’s playful tone’s a ruse: “We line up the keys and paint them with water.” But water will quickly evaporate. The paint is ephemeral. The cages have no protective coating. Not so easy to change things. The speaker continues: “We export our cages everywhere. / Packed in sawdust. Packed in wool.” Ah yes — the rest of the world can fashion itself after us, but our influence, packed in soft stuff, will be insidious. These cages recall the cages sculpted by the late Louise Bourgeois, cages she named cells. Uncanny how both poet and sculptor lock us out while at the same time drawing us in. We can’t help but wonder who will occupy these cages. Finally, the speaker “inspects the locks,” says, “One cage is a method. / One cage is a story.” These lines surprise, reverse the mood. Irony plays against order. A method, though it may cage, can serve for making art, for structuring a life. A story can be a key to knowing, to being in the world beyond the cage.

Joy and delight dominate “Embark” and “Little Wet Monster.” In “Embark,” we hear endearment as the speaker addresses a beloved in lines that kindle images of pregnancy and parenthood: “Sit here little mumsy, a red pillow / for your bunion.” But “Mosquitoes climb the delicate. / Thus in a back alley / archaeologists maneuver a pirogue.” Mosquitoes bite; the pirogue (open boat) is stuck, not fit for a journey. Risk is everywhere, but the speaker is lucky; he faces risk with a beloved: “Help me, sweet bread, / mountains unravel by the hour. / This isn’t what we came for.” Ah “sweet bread” — sustenance in a soul mate and beyond — the speaker seeks sweet, not bitter, and sings so with assonance: unravel / hour / for.

Befitting the title, opposites, overt or implied, appear frequently in Parable of Hide and Seek. Gratitude opposes despair in Sweeney’s rollicking loose ghazal, “Little Wet Monster,” a celebration of impending fatherhood. We hear the speaker implore his unborn child:

The cornfield winds its halo darkly

Come home my little wet monster

Time in the copper mine, time in the copper

Come darkling soon, come woe my monster

Distance shines in the ice like a flower

Come early little bornling

Images startle, convey foreboding. Birth is a trial; woes will pile up. Yet the speaker’s voice is gentle; the child is wanted, already loved: “Come whole my homeward early” intones the speaker. “You devour the night’s holy sound / Come home my little wet monster.”

Throughout this collection, we find disparate images yoked together, lines that tug in opposite directions, yet images and patterns recur, reveal the poet’s preoccupations. Most salient perhaps is his focus on language as method for facing a chaotic and threatening world. Sweeney’s speakers tell us “I rent / this language / to stay dry in” (“Holy Holy”); ask: “What is the method for hatching an act of speech” (“A Love Song”), the method for when “we’ve nowhere to go // and the oblique syntax of bones / repeats its inquiry / in the language of the world” (“The Sentence”). Ultimately, what Chad Sweeney shares with mischief, thoughtfulness, and generosity, is infectious joie de vivre to help us survive as self, nation, and planet.