A Marxian whelm of a pillowcase

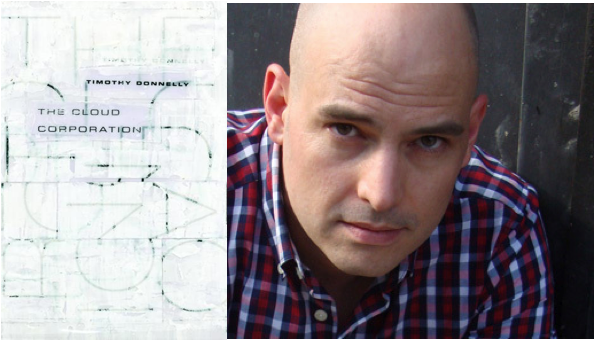

A review of Timothy Donnelly's 'The Cloud Corporation'

The Cloud Corporation

The Cloud Corporation

Timothy Donnelly’s second full-length book of poetry, The Cloud Corporation, is chock-full of feverish strings of iambs and strictly measured stanzas that deftly lilt their way into the subconscious. Donnelly’s virtuosic aptitude for employing traditional poetic form to deliver delightfully idiosyncratic content will come as no surprise to any reader already familiar with the poet’s previous collection, Twenty-seven Props for a Production of Eine Lebenszeit. As Richard Howard observes in the foreword to that volume, “every poem coils about its syntax like a sleek python of reticulated verbality” (ix). What moves The Cloud Corporation into distinctively new, and welcome territory, is Donnelley’s inspired decision to indenture this formal prowess into the structural backdrop for his text.

The poems in The Cloud Corporation are fundamentally aware of themselves as objects of production. Donnelly frames each poetic art-object as an aesthetic commodity with the reflective capacity to wonder “why clouds we manufacture / provoke in an audience more positive, lasting / response than do comparable clouds occurring in nature” (31). This approach frees Donnelly to embrace the role of aesthete even as he dissects poetry’s inevitable complicity in the construct of capitalism.

The Cloud Corporation is populated by a mélange of first-person personas with an array of spatial and temporal origins. There are historical, contemporary, and imagined characters occupying landscapes that range from ancient Mesopotamia to the 9/11 Commission Report. These voices are intensely communal, mapping themselves over a “we” that sifts through both time and space. Collectively, these protagonists, whatever their origin, strive to imagine “what it might be like to live / detached from the circuitry that suffers me to crave” (146). They systematically chip away at the finely crafted veneers of the poems they occupy, all the while rebuking themselves, and us, for our inability to see past them.

A cloud of hypocritical guilt looms over the proceedings, which constantly calls into question the efficacy of any resistance these voices prepare to implement. If a poem’s position as an art-object provides a soapbox from which to launch a program of resistance, it is also a potential prison, where aesthetic value is prized absolutely. “I don’t want to have to / locate divinity in a loaf of bread, in a sparkler, / or in the rainlike sound the wind makes through // mulberry trees,” writes Donnelly in the book’s fourth poem, The New Hymns, “not tonight” (10).

Just as he plays the restraints of form and meter against the emerging voices of these poems, Donnelly allows the notion of singular transcendent genius to collapse under its own weight. “Listen to them carry on / about gentleness,” he continues later in the same poem, “when it’s inconceivable / that any kind or amount of it will ever be able to // balance the scales” (10). Rather than pulling away from introspection and self-discovery, Donnelly writes straight into these modes, embracing them with a cacophony of self-reflective “I’s” all reflecting at once. The result of this rhetorical end run is a sort of communal transcendence that refuses to accept compartmentalization.

To call these poems political, at least in a conventional sense, would be a distinct misrepresentation. These poems make no attempt to call readers to any particular action, aside from a general resistance to the status quo. And yet, neither are they apolitical. The poem Dream of Arabian Hillbillies — an amalgamation of language appropriated from Osama Bin Laden and the theme song to The Beverly Hillbillies — searingly underscores the absurd repugnance of our contemporary political power structure even as it outlines, with businesslike pragmatism, the humble species of resistance we can hope to expect:

May your life

not be a lifelong movie of your life

but a steadfast becoming other than that

which you are: a slave to the power

fiddling among hills of fed clouds and shaken

into wonderment like a shot horse barely

gathering will to lay down with it, y’hear? (82)

These are not propagandistic poems of revolution, but neither are they a battle cry for the disillusioned. Rather than simply identify the ills of society, Donnelly deliberately exposes the systems, both internal and external, that prevent us from righting them. These poems are fundamentally disinterested in oversimplification; they strive to expand their net of introspection “to know the world’s big backslap // unhampered by the stream of this or any downpour” (92).

Donnelly presents us with a veritable Marxist tract for the twenty-first century, fueled by a nagging uncertainty about revolution’s inevitability. He redeploys complex Marxian notions such as commodity fetishism (“I hear the naked hands of strangers make // my dumplings but experience insists what makes them / mine is money”) with such simple poetic panache they resonate with unexpected clarity (70). The Cloud Corporation, in all its temporal and self-reflective tumult, unearths the taproot of contemporary political malaise — our internalization of the new manifest destiny, an unwavering belief in the inevitable expansion of capitalism.