'It feels like painting a larger picture'

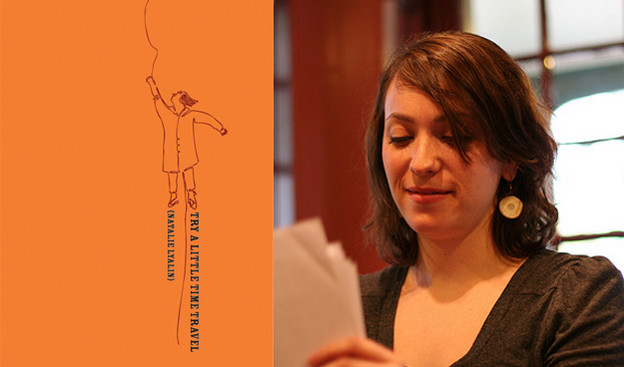

A review of 'Try a Little Time Travel'

Try a Little Time Travel

Try a Little Time Travel

As the title poem of Natalie Lyalin’s Try a Little Time Travel makes clear, this book is not concerned with telephone booths or Tardises, but rather with “time travel” as a mental process. The reader is exhorted to “Close your eyes, // And think, Grandmother, / I’m coming to you, live!” (6). In these poems, time travel becomes a method of inquiry, of digging through the shifting sands of memory and desire to discover imaginary truths about imaginary pasts and futures. Of her own journey in “Try a Little Time Travel,” the speaker reports:

I learned:

I was not evil,

Fjords made a screeching sound when formed,

G-d is not vengeful,

My uncle smothered someone in an open field. (7)

This collection of heavy biblical lessons is something of a surprise at the end of a poem that began by glibly encouraging readers to try time travel “instead of sexing / one night,” and that along the way entertained the pop-culture commonplace about whether it would be advisable for a time traveler to kill Hitler. But these shifts in register are part of what makes these poems interesting and what allows them to cover so much ground. In the poem “Burn, Burn, Burn the Air,” for example, a flippant, matter-of-fact tone makes a startling juxtaposition with the grim subject matter:

Anyway, we went

Walking. The galaxies tried to part us. We were then

Pardoned for the war crimes. It was only after that we

Lead them to the mass graves. With some gravitas we

Dug for survivors. There were none, so they hanged us!

They hanged us in the brightest spot of our youth. (2)

With this juxtaposition in mind, the line about killing Hitler becomes more than a cliché. This series of quasi-comic reversals (being pardoned for war crimes before revealing graves, digging in graves for survivors) delivered in straight-faced, declarative sentences is strongly reminiscent of Yiddish nonsense tales for children. For example, the opening lines of a Yiddish story called “The Pain in the Neck” are designed to delight children through their continuous flow of contradictions: “Once upon a time there was a very rich poor man. He had no children except for nine daughters. His oldest son took it in his head to go to the fair.”[1] Lyalin brings this comic structure closer to the theatre of the absurd, turning the real impossibilities of the Holocaust into grim entertainment.

Families figure prominently in these poems as a form of “time travel” in themselves, their generational structure linking the past with the future. A poem called “I Had This Hair When My Dad Was Alive” begins with seven relatively coherent lines reflecting on a past in 1980s Poland, when “it was hard to find boots and stockings” (14), then careens forward into thirty-nine relatively unconnected lines that loosely share a theme of life’s transitions, suggesting a contrast between the past’s existence as pat stories and the chaos of the present. But if the past is story, it’s also fantasy and guesswork, making it not all that different from the future. In addition to fathers, uncles, and grandmothers whose lives are half remembered and half imagined, there are a lot of babies and children in these poems. In a poem called “To All My Babies,” the speaker apologizes to her eerily and nonspecifically plural “babies,” who seem almost insect-like in the way that they’ve scattered to the winds. And in “All the Missing Children Go to Florida,” Florida is imagined as both haven and mother to the children on milk cartons, who roost in trees and taunt those who would bring them back to their homes, boasting about their alligators, orchids, and “the stench of [their] / Swamp hearts” (5). In both these poems, the speaker imagines a future for children whose fate she cannot know as a way of comforting herself in their absence.

What Lyalin’s first book, Pink and Hot Pink Habitat (Coconut Books, 2009), accomplished with invention, this chapbook does with increased focus on cohesion and coherence, which invites from the reader different emotional responses. The mothers, lovers, fathers, grandmothers, uncles, and children who populate these pages all seem to understand that the insight into one another provided by all this mental “time travel” — these memories, dreams, fantasies, and projections — is no less real for being imagined.

[1] “The Pain in the Neck: A Nonsense Tale,” in Yiddish Folktales, ed. Beatrice Silverman Weinreich, trans. Leonard Wolf (New York: Schocken Books, 1988), 35.