The hymn of journals, poetic and public

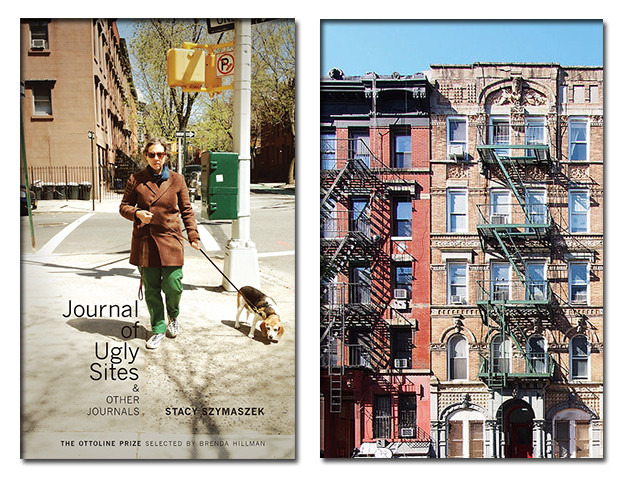

Journal of Ugly Sites & Other Journals

Journal of Ugly Sites & Other Journals

With today’s ubiquitous social media and all that sharing entails, the idea of poetry that delves into the personal and utilizes actual journals would command an especially astute and unique precision — one that Stacy Szymaszek’s Journal of Ugly Sites & Other Journals deftly delivers, reminding us of the raw power of the poetic personal / personal poetic, and how uncommon poetry with this kind of depth is nowadays.

Reading this book reminds me that the current Facebook-Twitter-Instagram environment is no match for the curated and hymn-phonic id, as extrapolated through an artistic lens of a writer in high command of a journal she renders and crops into a poetic-nonfiction narrative. This is not “confessional” poetry, with all that connotes, of Plath et al. This is not even under the tired moniker of “personal” poetry. Despite the fact that Szymaszek has indeed pulled from her journals, it does not feel like “mining” journals “for material.” It is something more chiseled.

What this book is feels like a stained glass window, a kaleidoscope where these journals have been strained and filtered out as poetry — and we are listening to the hymn in a church’s pews on a late afternoon, with the stained-glass light rays obscuring our vision. Not just poetry, not just journals, but something more intriguing, in between. What happens between the moments of recollection and chronicling and the poem? Reading this book is like the answer to that question, without realizing we are asking the question or searching for the answer. It just is, like life just is.

Szymaszek’s Journal of Ugly Sites is actually inspired by a prompt from the poet Bernadette Mayer, to chronicle “beautiful and/or ugly sights,” as an idea for keeping a journal (as noted at the end of the book). The author’s wordplay on the “sight” from Mayer’s original and the “site” she uses for her book title makes the above distinction on this work, Journal of Ugly Sites, all the more intriguing. The title feels both anticipatory (what will Szymaszek deem ugly? “// how much is really ugly when eliminating litter //”?[1]) and revelatory — what Szymaszek deems ugly sometimes doesn’t always seem exactly ugly really, but something called “real life” —

// failed multitasking due to years-long avoidance of proof of residence —

thinking I’m still living off the grid, then 100 things proved me // (82)

The choice to draw on these journals — indeed, the chronicling of real life, the inexplicable but understandable ways that life moves, at times, unfairly — shines through that stained glass as poetry.

What made me go back to this work again and again were the effects of the cropped imagery of life’s snapshots up against each other, telling stories, in the break, through the visual read:

// shame when meeting someone who can pronounce my last name the real way like inauthenticity is just easier for me // (82)

// expression of confidence followed by the ever so slight fear that patterns can’t be broken // (84)

What results is the feeling of being with the author minute by minute as she trudges through her everydays. Coming from one of our pillars in the poetry community, bits of arts administration work come through these long poems as well. One cannot read this book without thinking about community. Reading it is a window into the world of someone working selflessly (at the Poetry Project) for other poets, usually with seriousness, sometimes cut with gallows humor and exasperation, sometimes with the mundaneness of everyday business:

// fighting with Ukrainian Home waitress standing up

for my committee we will not be back // (80)

// panicking that I forgot the key so typical then finding the key so typical // (80)

As Szymaszek clocks in and out, week after week for poetry, we learn she deals with health challenges, small moments of relationship strife and deaths of beloved pets. The book becomes an alternative soundtrack of an autobiography, like an opera or even a minimalist Philip Glass score. Sometimes Szymaszek’s lines are short with more space, as in the beginning lines she wrote after the death of her dog. Sometimes the lines are a full orchestra when they go long and prosey. We see many tracks — track 1: health; track 2: personal relationships; track 3: departing, beloved pets; track 4: the job in the nonprofit world; track 5: friends and community; track 6: the biological family back home; and more. It is in retrospect that I see Szymaszek has seamlessly merged these tracks — I didn’t consciously notice them as separate tracks while reading. They were all woven together; something about their vividness does not go by in a blur. Memories appear at what seem to be ordinary moments and what came before or after is not always visible, because life moves on —

// having to say “I’m gay” in this day and age // (81)

Sometimes it’s laugh-out-loud funny and then the reader almost feels guilty for laughing because something very serious and tragic happens not too much later. But that’s life, right? The author captures those daily moments that annoy the hell out of us but we never bother to remember:

// dropping wallet then when bending over sunglasses falling out of my pocket // (81)

The simple act of capturing life moving on may look simple, but it’s not as easy as it looks. Szymaszek’s work replicates moments of time passing, of mourning, of abrupt changes in life that we have no choice about — and the reader glides along not noticing the blinks and stops, because Szymaszek has us in both a holding pattern and a sea of life’s movements.

It’s not often we see the intricacies of the behind-the-scenes never-ending work of the arts administrator in poetry, and with subtle humor at that: this is the life of the poet who works constantly so others in poetry can succeed:

wondering if it was wise

to finish the NEA

in record time (46)

// another person surprised that I work here full time like I’m volunteering here

just because I love poetry // (85)

thievery at panel on community decide not to call the police (33)

everyone who is not me has blown this deadline (97)

At times work merges with the personal:

if burnout is disavowed grief will I come back to life

if I publicly admit how bereft I am? (120)

And to still continue writing one’s poetry while doing those grants — and hoping to count on the support of others —

Williamsburg: series that has audience say their names and which reader they’re

supporting no one is there supporting me (82)

posting a link to something nice written about my work on Facebook only 2 people linking it // (111)

While the self-effacing nature of these lines belies humor underneath, I hope the opposite of the above lines happens with this book — this is a necessary collection in 2017 that gives a needed voice to a queer nonprofit worker, who balances health scares and navigates a committed relationship. It is also part portrait of NYC; the subtle changes of the city — in particular the stretch of Second Avenue that Szymaszek walks as she schlepps to and from the Project — are chronicled in infinitesimal detail:

East Village: rush hour F stops at 2nd no people pouring out // (112)

East Village: … // old woman living on social security panhandling to make ends meet // (133)

East Village: how many days would I be sitting on this bench before seeing a familiar face // (130)

What is remarkable about observations like the ones above, seemingly routine moments — a train stops, someone panhandles, our writer sits on a park bench — that out of context feel like a Diane Arbus or Helen Levitt photo, is that while reading them, Szymaszek is enduring especially challenging and tragic moments, and in the midst of it, she still sees the world pass by with pinpoint precision. That is the mark of a poet, a real poet, an urban poet, a poet’s poet, a people’s poet — one who is living in the world while chronicling it, while rendering it poetic, while her own life unspools in a metaphoric stream of consciousness and crystal clarity. That’s the beautiful crux of this book.

In Szymaszek’s poetry, time slows down, framed in ways we would not have seen otherwise — and it’s framed in a merging of poetry and nonfiction that is difficult to forget. It is a hymn gone slow-mo, a movie on both fast single frame and sixty-four frames per second. You the reader are caught in it, because no doubt your life at times has mirrored fast and slow like this too. In all of this, our author continues her work on behalf of — after all these years — thousands of poets and audiences. This is that person’s life that makes it possible for you to come to those open mics, those marathon readings year after year, those Monday and Wednesday and Friday nights, those workshops —

// late Wednesday nights walking down 2nd home feeling like an eternity away // (92)

This is that life. This is that poet’s life. I can’t help but be reminded of one of Szymaszek’s lines:

“we’re going to do a redemption” ears perking up “do you understand?” yes I think I do // often I am caught between a rock and a poet // (129)