The hurts of wanting the impossible

A review of 'Supplication: Selected Poems of John Wieners'

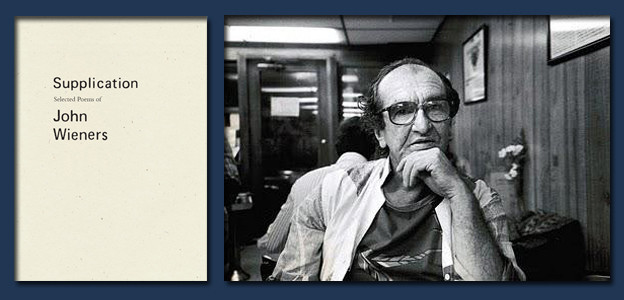

Supplication: Selected Poems of John Wieners

Supplication: Selected Poems of John Wieners

Shortly after the sad news of her death, I went to a screening of Chantal Akerman’s last film, No Home Movie.[1] The woman who introduced the film assured us — twice — that Akerman’s work is “unsentimental.” I considered the value of her insisting on this as on screen Akerman’s camera sat fixed upon her aged mother reminiscing, doing chores, and towards the end trying to eat a meal — with the help of a condescending nurse — in the grip of an unsettlingly deep and chronic cough. At night, Akerman picks up the camera and seems to careen through her dying mother’s dark apartment, audibly sobbing in the space we share with her behind the frame. The moment is raw, certainly, and that adjective starts to reach for its habitual partner: unsentimental, which is the name we give to that which does not seek to falsify or exaggerate feeling. And yet feeling is often an unequal proposition, and its supposed exaggeration may be experienced by one party and not by the other who finds in it, instead, a readymade accusation or parting shot. The person who calls a feeling “exaggerated” may be precisely that person who doesn’t want to be overwhelmed by our deep feeling. Often this person would like to know just what is up with you and your mother, anyway (but try to understand Akerman being subsumed with grief for her own). Often you are standing outside this person’s house, calling their phone, or just at home with the knowledge that, as John Wieners writes in “A poem for movie goers,” “My lover’s thoughts are not / of me at all.”[2]

Wieners is not a sentimental poet, but the poet of sentiment and its exiles. Again and again in his poems, the speaker imagines loves lost, loves elsewhere. His “Sickness” begins haunted: “I know now heard speak in the night / voices of dead loves past, // whispered instructions over electric air / confined or chained” (63). The poet treads carefully:

Do not tamper with the message there.

Do not let silent, secret reaches of the heart

invade you here

kept at bay long enough but he is

gone who would protect you from them.

Radical vulnerability. He follows it, several lines later, with spooky calm:

Cool wind blows in an open window,

I am happy being alone.

It seems time going down an eternal staircase

wound up at ease with me.

Wind and winding and winding up, in these lines, all talk about recurrence. Nothing stays dead, certainly not in the world of feeling. Longing and renunciation aren’t states we can occupy once and for all; they vie:

I want only the mystery of your arms around me.

Dont worry about eating my food.

Single strand of light falling on his bare shoulder

In the closet.

Won’t you come and see me again,

please?

The dragon lies on its side. (64)

Is the dragon the lover, promising to be docile if he receives this much-desired visit? Or is it the guardian of the world’s treasure, that will only permit our desires to be fulfilled when it takes the occasional nap (even the force of prohibition dozes sometimes)? It’s not clear — as it isn’t clear whether “his bare shoulder” belongs to the “you” who is being asked to come over. The poem is layered with memories and fantasies, selves and others in this and different times. They might or might not coincide, but the poet, here, is resigned and open. “Dont worry about eating my food” — there couldn’t be a sweeter permission. Sentimental moods keep the phone company in business.

Wieners is also wicked: “I fingered his wedding ring / as I blew him” (72). And an imp. In a piece from 1988, Wieners’s friend and executor Raymond Foye tells the story of eating dinner with Wieners and Simon Pettet:

Simon and I opened our fortune cookies: “Gather all information that could be remotely apropos,” mine said. “You will soon be honored for contributing your time and skill to a worthy cause,” read Simon. “What does yours say, John?” we asked eagerly. “I ate it,” he replied.[3]

Easy prophecy is easily swallowed. He’s deadpan. In “The Lanterns Along the Wall” (a statement of poetics Wieners wrote for a class of his friend Robert Creeley’s), Wieners speaks of the magic with which poetry can fill emptiness and solitude with beauty and “tranquillity.” Of that magic, he writes, “There are no other forms as far as ultimately I am concerned. No drunkenness can equal purity. Or, other forms, simple address to the prime force of love. Love, not in the sense of kindness or patience, but sometimes trespassed sensual energy” (183–4). Not in the sense of kindness or patience, no! An economy including “sometimes trespassed sensual energy” is characteristic of this poet who adjusts and conjures, stands in shadows, gets sick in his room, “running the most beautiful blue water / in the sink / vomiting strawberry and green” (40).

Sure, Boston sucks, and we all hate it. But I love to think of this moment, when it’s enough of a small town that Wieners can happen to see his mother “talking to strange men on the subway” (59):

doesn’t see me when she gets on

at Washington Street

but I hide in a booth at the side

and watch her worried, strained face —

the few years she has got left.

Until at South Station

I lean over and say:

I’ve been watching you since you got on.

She says in an artificial

voice: Oh, for Heaven’s sake!

as if heaven cared.

I can hear her saying it, with that touch of the “artificial” that draws forth boys/sons to wonder forever if, when their mothers play at being scandalized, they conceal — and perhaps wish to be seen concealing — a knowingness about desire that will also never, ever be explicitly acknowledged. Hence the delight in catching her unawares, and creating for an instant a scene in which the pair stand outside the roles of mother and son. It can’t last: the remainder of the poem “My Mother” reads:

But I love her in the underground

and her gray coat and hair

sitting there, one man over from me

talking together between the wire grates of a cage.

“One man over” isn’t much of a displacement — but enough, in this case, to see clearly the cage through whose grate communication (the most intimate? the least?) is fated to pass.

It’s fun to sit on the subway in New York and read this new Wieners collection with its one-word title, black on cream: Supplication. Wave Books’s austere design suits poems that have been sacred to me since I was handed them as talismans, years ago, by poet friends. How much recognition do we want someone whose true home is “underground” to get? Underground because he chose Boston, lyricism, and a courtly remove. And more, because he chooses perdition: “Damned and cursed before the world / That is what I want to be.” Poet and critic Andrea Brady, in her work on the poet’s archive, quotes Foye: “Nobody had ever seen anyone throw themselves into the abyss the way John did.”[4] Why does a person throw himself into the abyss? Why does a person take heroin? And then write of it, “But I don’t advise it for the young, or for / anyone but me. My eyes are blue” (75). Two lines that manage to be all at once knowing, greedy, arrogant, assertive of a special power and also, to my ear, aware of the hollowness of that assertion (it’s arbitrary and comes too readily to hand). Drugs are for escape, they’re for posturing, they’re for denaturing the visible. But in the case of this poet of loneliness, they are also a way to “collapse in a heap on the bed of the world” (75). Denied our lives, we seek oblivion, and hope that beyond or through it we might be permitted to alter the order that foreclosed our true existence from the outset. Collapsing, dissolving: we have been taught to act, but Wieners knows it’s better, instead, to beg — to be convincing, under extreme pressure, by manifesting preferable alternatives with the allure of a mirage. He chooses supplication.

The editors of this volume — Joshua Beckman, CAConrad, and Robert Dewhurst — provide much interesting new material while also preserving the best from Foye’s earlier selection. Dewhurst is working on a biography and a complete poems. There is more scholarship underway, and more of Wieners’s journals — full of poems themselves — and letters coming out, particularly through the efforts of the CUNY Lost and Found series. It all seems of a piece, a lifelong project at the scale of a life. Wieners intersected with many poets, but the sense of him, biographically and in these idiosyncratically compact lyric poems ripe with indeterminacy, is solitary and original. His sexuality (vibrant but also vexed by the mores of the times), his clarity somehow heightened by a real experience of mental dissolution, and his tenderness remind me of James Schuyler. His independence and his mysticism recall David Rattray. And with another outsider, Rene Ricard (who called Wieners his mother), he shares naughtiness and woundedness and — at least in poetry — fearlessness. “Now I stay away from the bad / neighborhoods where I lived. / The bad blocks of the heart,” writes Ricard.[5] And Wieners: “For me now the new: / the unturned tricks / of the trade. The place / of the heart where man / is afraid to go” (15). Our freaky, funny underground mother, may we often cross his path.

3. Raymond Foye, “John Wieners: A Day in the Life.”