Hundred-spired muse

A review of 'From a Terrace in Prague: A Prague Poetry Anthology'

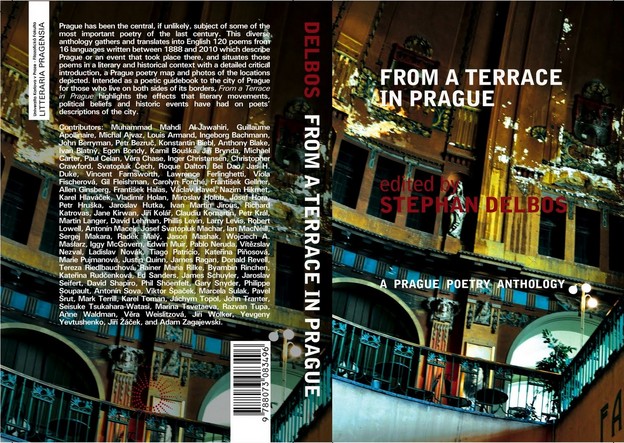

From a Terrace in Prague: A Prague Poetry Anthology

From a Terrace in Prague: A Prague Poetry Anthology

Prague has pervasive literary associations, a fact not overlooked by the hawkers of souvenirs and proprietors of restaurants. In the center you can buy a Kafka mug or t-shirt and have lunch in a pub emblazoned with images from Hašek's The Good Soldier Švejk. If that’s not to your taste, there is also a restaurant named after Rilke. Stephan Delbos’s anthology attempts to go beyond this tourist veneer. Though the anthology is styled as a guide, the intentions are bolder. As Delbos, a poet, journalist and translator from New England, writes in his preface, “Walking through Prague with these poems in mind, one has an indelible awareness of the lineage of poetry written in and about these streets and buildings, many of which have remained virtually unchanged for centuries.” In short, he is rescuing the city’s literary heritage from bastardization.

However, the rescue mission comes with complications. The anthology cuts across many styles, languages, nationalities and periods. Poets included range from Jaroslav Seifert, who is intimately connected with the city, to Robert Lowell, who wrote of the city as a distant spectator of the 1968 Soviet invasion. The poets are not necessarily opposites, but they are handy poles in which the poetry represented in this anthology falls. The breadth of poems demonstrates how poets have engaged with their city’s symbols and atmosphere. The result is an anthology of many Pragues.

One constant of Prague’s poetic heritage is that it has acted more as a muse than wellspring of poetic movements. Apart from one exception, to talk about the city’s poetry does not imply a school in a formal sense. Generally, the city’s poetry reflects an interaction of diverse artists whose connection to the city is as singular as the work produced. The earliest poems included here certainly reveal an outwardness of inspiration transposed over an inwardness of subject matter. Symbolism was an especially important movement for the Czech poets at the end of nineteenth century. Echoes of Baudelaire’s urbanism melding with concrete images are found in Antonín Sova’s “Old and New Prague.” However, Sova shows traces of more social and historical preoccupations. Whereas Baudelaire likened Paris to “a hard-working old man,” Sova writes:

But Prague rumbles below so quietly in this idyll!

All the proud flourishings of culture are outside the Castle!

Progress and claims to glory breathe through Prague

And she is a healthy, hearty child!

Symbolism may have encouraged a focus on the city but this passage shows a mindset and a celebration that is local. Given that the poem was written in the nineteenth century, it is difficult not to identify the tone with a growing Czech national consciousness that saw itself outside the confines of the city’s main emblem long ruled by Austrian kings.

Paris continued to be an important source of stylistic innovation. Surrealism, especially that of Apollinaire, resonated strongly with poets of the early twentieth century. Importantly, his piece “Zone” makes reference to the city. Does this fact alone justify the poem’s inclusion? Yes, if we take the intentions at face value. However, the passage concerning Prague does more than check off landmarks.

Horrified you see yourself etched in the agates of Saint Vitus

You almost died of sadness the day that you lived

To see yourself like Lazarus bewildered by the day

the hands of the clock in the Jewish quarter run backwards

And you too crawl slowly back through your life

while climbing to Hradčany listening at night

To the Czech songs of the tavern

The key elements of the city; St. Vitus Cathedral, the Jewish Quarter, and Prague Castle, become fixed in Apollinaire’s voice. He is not representing the city in itself; rather the city is a means for him to realize his artistic vision. This approach makes the poem more about Prague than a poem dealing directly with the city because the poem makes claim to the inspiration he found there.

The one major Prague-based poetic movement, Poetism (Poetismus in Czech) took its cues from Apollinaire. The movement never spread beyond Czechoslovakia, despite the involvement of the country’s leading poets, such as Jaroslav Seifert, Vladimír Holan, Vítězslav Nezval and František Halas. The poems, which represent the movement included in the book, are by Nezval and Halas. As this very small sample shows, homogeneity is difficult to ascribe. Structurally, Nezval built both the poems in the anthology around repetition. For example, “City of Spires” starts:

Hundred-spired Prague

With the fingers of all saints

With the fingers of perjury

With the fingers of fire and hail

With the fingers of a musician

The poem trumpets and blares, and like “Zone” the poem is not a picture of the city; rather the city is taken, pulled into pieces and reassembled. It is joyous in its openness, shepherding all aspects of the city into the lines. Halas in contrast was more subdued. His poem “Prague” ends thus:

Under blue sadness

the blue blood without oxygen

you are boiling over

Following that train of yours even your dumps are boiling

painfully boiling over

with beggar’s burdock and stinging nettle

may she catch stones

Whereas Nezval seems to be proclaiming his poem from the city’s Petřín Hill, Halas is floating across, suggesting disconnection. Therefore, as we can see Prague’s clearest moment of poetic fellowship revealed great variety.

The invasion by Nazi Germany was the end of the movement. The foundation of the communist regime continued to stifle any new local poetic affiliations that were not officially sanctioned. Nezval started to churn out party appeasing doggerel, whereas Holan and Seifert — who had both been fervent proletarian poets before the war — found their voices in opposition or noncommitment. Holan’s “Simply” with its myriad of voices, its almost novelist’s precision married to a melancholy resignation, shows how difficult it is to read the era into the poems.

We stood outside the tobacconist’s and some of us

had small change and some had none …

On the storefront was a notice:

This shop is for sale. Someone has scrawled under it

in chalk: FOR BUGGER ALL!

We looked at it for a while and then

walked to the pub.

The lines are timeless — both in its expression of how fine divisions run and the evocation of frustration and boredom in a seemingly simple scene.

Poets who stood more obviously in opposition are of course represented. However, any attempt to unite them tends towards oversimplification. Egon Bondy, who was connected with the underground avant-rock band the Plastic People of the Universe, is in his poem acerbic toward the custom of young Prague lovers meeting to kiss on the first of May, a tradition linked to the nineteenth century Czech “romantic” poem Máj by Karel Hynek Mácha. Jáchym Topol’s “Moreover It’s Clear” evokes the latter years of the regime. The tone is not so much defiantly political as bitter and personal, especially when he writes:

haggard mugs

at the Moskevská stop

remind me of the existence of people

who don’t give a shit

Such despondency doesn’t always require a totalitarian regime. It’s important to remember that as much as Topol was reacting to the political conditions of his country, he was also like poets in the West striking out at more universal moral decrepitude. Having said that, the drab concrete of socialist architecture no doubt exacerbated those ills.

When we take into account the lives of Holan, Bondy and Topol along with all the other poets of the communist era, historical and political reductionism becomes problematic. These three poets were in opposition; however, their relationship was complicated. Holan as stated earlier was a former party member and Bondy, despite his strong association with the Prague underground, always identified as a Marxist. Only Topol showed no political affiliation. Other poets included, such as Miroslav Holub and Jiří Žáček, occupied a grayer area. Holub was a professional immunologist during this time and Žáček worked for the state publishing firm. Yet, the latter offers the best view of the city’s suburbs in his poem “South City”:

Battle zone for high rise brats,

for wolf packs. Whose orphans are you,

floaters from daycares, accustomed to dummies and cats?

If you take after your father too,

Subsuming all poetry under the banner of dissent would marginalize this particularly whimsical view of the city. Poetry does not always align itself with our neat ideological divides.

The more strident political voices came perhaps from the outside. Lowell’s “From Prague 1968” appears to be genuine in its protest even if the subject matter was second hand. The inclusion suggests that the Prague we are dealing with is also one of symbolism as much as cobblestone and churches. In fact, with a collection such as this one, it is important to remember that the urban landscape presented is in part figurative. Ginsberg on the other hand could claim to have felt the pressure of the regime when he was expelled in 1965 after being named Král Majáles, or the King of May, also the title of his famous poem included here. It is not so much the poem’s references to his short time in the city which makes it fitting as the way Ginsberg and the poem have become part of the city’s mythology. Ginsberg was an important figure for the Czech underground of the 1970s. He also serves as a symbolic figure for Prague’s current English language poetry scene — no wonder a recent anthology representing this international literary renaissance was called The Return of Král Majáles.

However, the anthology shows that the poetry of opposition didn’t only congregate in Ginsberg’s camp. Pablo Neruda, who famously adopted his sobriquet from the Czech writer Jan Neruda, visited the city while in exile. The El Salvadorian poet, Roque Dalton, was in Prague because he had escaped execution by a right wing dictatorship in his homeland by fleeing to Cuba. The Cubans later sent him to Prague. His poem, “Tavern” is a wild mix of voices in which Ginsberg is referenced. The inclusion of Dalton indicates more than ideological divergence. Placing the poem immediately after Ginsberg’s in the anthology also means there is one poem referencing another event in the anthology. Of course, it is selection, but history is selection, and an anthology is a way of doing history. It is history of demonstration, connection and juxtaposition. It is the history of giving as much voice to the actors as possible.

Other émigrés, exiles and expats enrich this history further. Ginsberg is only the most notable example of the English poetry which is increasingly becoming part this city. Australian Louis Armand, who is a prominent member of Prague’s international poetry community, offers in his poem, “Leden” (the Czech for Januaury), a poetic vision as much at home in Prague as the poems of an earlier era. Through Justin Quinn’s “Seminar” we get a humorous and sympathetic sense of what it is like to teach the language of this historically new community, which these two poets are only a small representation. One pity is the absence of Sylva Fischerová, whose “The Language of the Fountains” is a wonderful evocation of the city and seems to evoke the very themes of language and place on which this anthology turns.

Russian is another language which is in some way a part of the city. Many Russians came to Prague after the revolution and civil war. Nabokov’s mother was a resident, as was Marina Tsvetaeva, who lived in Prague from 1922 to 1925. There she composed “Mount Poem” and “Poem of the End.” The inclusion of Tsvetaeva forces us to address the idea of “poetry of place” as it applies to Prague. It is only that we know the poems were composed in Prague that seems to connect it. Unless we assume that the city inspired Tsvetaeva in a way no other city can. The notion is not in itself misguided, but it is a bold assumption and one that is hard to prove.

Tsvetaeva’s correspondent, Rilke, further suggests the complexity of poetry and place. That he was born in Prague as part of its German speaking community and wrote about his hometown makes him an obvious choice. However, his relationship with the place was tenuous. When childhood and memory appear in other works it is more internal and impressionistic. The two poems in the anthology, “Hradčany” and “Out of Smíchov,” are as pregnant with significance as his later work, but they are no more of the city than other of the Prague German writers who are absent. Rilke’s stature among English speaking poets is undeniably greater than those others. However, it is a shame that poets such as Franz Werfel and Max Brod are missing, when Germanophones Celan and Ingesborg are included. Given an already rich representation of poetry from and about the city their place is surely here too.

Prague’s place as a literary city is undeniably unique, but it is unique in that all cities are unique. The “Golden City,” “The City of a Hundred Spires,” is a culmination of a long history, a history which is constantly unfolding and of which poetry is a record and an agent. While it would be a mistake to ascribe to Prague some privileged place among urban muses, as this anthology shows, poetic currents are ever present in its streets and its spired skyline.