Honesty is the best policy

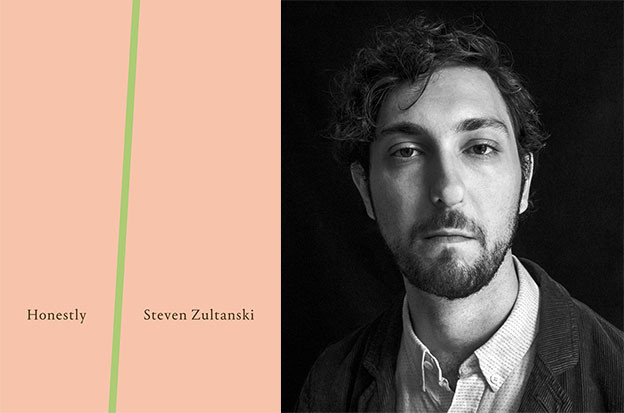

Honestly

Honestly

What are we to make of this short book? Is it poetry? Well, it doesn’t look like poetry. It is set up like prose, but these aren’t prose poems. They look like stories, or chapters. But are they? There is a voice, a narrator — is it the author, is it Steven Zultanski? — we aren’t quite sure. No name is offered. Let us call him the narrator. And are these sections, or chapters? This certainly doesn’t seem to be a novel, nor a collection of stories. And they are all in the first person.

The voice here can be described as unprepossessing. The tone of these stories — are they stories? — is quiet, unassuming, consistently conversational: I thought I’d just share this with you, it seems to be saying. The narrator is a friend, someone you have coffee with. But before you can finish telling him about that stultifying meeting you had to sit through this morning, he tells you a story that shuts you up for hours, for the rest of the day, for the rest of the week.

Many of these stories start similarly: the narrator tells us about falling into conversation. He is at a party, he is with his friends. They’re just hanging out. His friends tell him stories, they talk to him; and he has stories too and then he passes them all along to us, one after another. There are nine of them. The sections, or chapters, are untitled, separated by blank pages, each starting with an asterisk. That’s it, nothing else. This is a terrible and terrifying and, perhaps, from time to time, beautiful world. And when we come across a poet who can bring it to us, in such a quiet and uncompromising way, we realize we need to pay attention.

The unnumbered sections are, each of them, or almost all of them, standalone tales: we learn about his old buddy, he was kind of drunk, this is what he said. In another, someone tells the narrator about his father. In a third, the narrator tells us how much he misses his girlfriend and if she were around, if only she were around, what he would say to her. We also learn about the intriguing, enthralling, ultimately tragic life of the narrator’s great-uncle. We feel like this narrator is a friend talking to us in the unadorned, unguarded way we’ve come to expect of him. He seems to move from topic to topic. He’s just talking, just chatting, the way one’s friends do. The tone says: here we are, we’re just being us. But the fact is, I am here for you. I am here for you to have someone to talk to. That’s an important thing, isn’t it? Just to have someone to feel free to talk to.

But this book is about something. As these conversations and monologues, seemingly random, apparently casually collected, at first palpably purposeless, or nearly so, unspool for our delectation, they come to accrue a fateful, implacable weight.

A friend is talking to him at a party, at least that’s what we’re given to believe. At first he’s telling the narrator a story about corrupt labor unions, and corporate bosses and the allegedly purer-than-driven-snow environmental organizations, and the mob too, how they are all in bed with each other — are we really supposed to be buying this? — but then his friend segues into a much realer, more penetrating story. It’s about his parents and the weird fucked-up life they’ve made for themselves, having separated decades ago, without exchanging a word in years, but yet continuing to live together, under the same roof, communicating solely by writing notes which they leave around the house, which are certainly never read by the other.

In a book to a large extent made up of conversations recollected, real or imagined, and a few books read and reread, books that are real or perhaps drawn from the writer’s imagination, we come to be presented with more contes, some straightforward, some carefully convoluted: the author lies abed and thinks of movies he’s seen, starring shockingly mordant children. Then, we are regaled with snatches of party chats with a friend, frankly confessing how the idea of death has invaded the everyday round of routine with her much older lover. At what might be the same party, another friend, in his drunkenness, may or may not take such spectacular exception to the writer’s own tipsy, fairly ridiculous, comparison of James Dean to Steve McQueen in The Blob that he rains such imprecation on the writer’s head, and then his girlfriend’s as she takes him home and tries to put him to bed, that in this one unhinged PBR-fueled rant, according to the narrator, as his usual mild manner cracks wide open, he reveals terrifying — or perhaps terrifyingly ridiculous — depths of hellish, smoking, raging resentment. Is this what lurks beneath his apparently good-natured mien?

The book proceeds, one story after another, each told in the same empathetically affectless way. Eventually he comes to tell us that he’s finally gotten his own apartment. A place of one’s own. Fantastic. Into even the most precarious life, perhaps, some good luck may sometime come. But wait a minute. What’s that noise? Is someone trying to get in? A home invasion? Could this happen to someone like him?

The closet is cramped.

The bathroom is narrow.

There’s nothing to crouch behind, nothing to hide under. The front door is easy to pry open.

Someone could walk right in.[1]

This is a terrible world that we have to live in, the book tells us. It is just this dangerous. It is shot through with loneliness and longing and struggle and poverty. The book starts off with and circles back to the author’s great-uncle, Dick Stryker, a mysterious, nearly forgotten member of his extended family. Not until the author finds Stryker’s annotated edition of Joyce’s Ulysses does he suspect that one of his blood relatives, decades before him, might have had a life like his. As he digs deeper, he learns that Stryker was an esteemed composer who worked closely with Judith Malina and Julian Beck in the formative years of The Living Theater. He collaborated with the likes of John Cage, Ashbery, and O’Hara, with Jackson Mac Low and others whom the author, on his own, has come to esteem and revere. And yet Stryker died alone. We come to see his precarious life as emblematic: a gay, WWII conscientious objector who served time for his beliefs, who struggled all his life, who some might say was defeated by life, brought down eventually by poverty and bad luck and old age and ill health, who certainly has been nearly completely lost to history; when the narrator approaches her Judith Malina does remember him, but only just. Stryker becomes, in a way, the presiding deity of this book, returning at its close to remind us that we are indeed obliged to read this through, to see this book to the end.

After meeting Judith Malina, the narrator reads her diaries and finds mentions of his great-uncle. He also uncovers her accounts of horrifying dreams — dreams of home invasion and violence. Yes, more home invasion — apparently prompted by stories Dick Stryker told her, stories about his truly nightmarish experiences, not brought by dreams but lived day in and day out when he served time in federal prison. The world we now see we live in, as we read all this, is a frightening, threat-filled place, peopled with things that can go wrong, people who can — given half a chance — prove just how wrong they are, how angry, dangerous they are. A world filled with malice and madness. A world not particularly safe for writers, or anyone who is trying to live a witting life. It is a world very much like, in short, the world we live in.

Why is Stryker’s story so important to the narrator, to us? Is it because the life he lived, we come to realize, may very well be no different than the life so many of us are living right now? Is that why the narrator is so riveted by his great-uncle’s tale? A wonderful opportunity he had, a golden youth, walking among the greats of his time. And, yes, great youthful suffering came his way too. When it comes to suffering, can we compare ours to his? Perhaps not, but reading his story reminds us, perhaps, that our suffering is real too. Maybe. And then comes his fate, his terrible fate. Is that our fate too, we wonder? Altogether alone, largely forgotten. The narrator asks himself this question. Of course, as we read this, we realize that while the odds of us dying under these conditions — quite possibly alone, almost certainly forgotten — are high, Uncle Stryker did beat those odds. He has a nephew who has now made it certain that we will remember him. And what were the odds of that?

Then, at the end, the writer and his lover are lolling comfortably in bed. He’s telling her how much he loves her. He wonders if he tells her that perhaps too often. At his request, she tells him a story. It’s from her youth and it’s all about asparagus, white asparagus, how it is grown:

it’s a process called etiolation, have you ever heard that word before? When something’s etiolated, it becomes a little blander, it becomes

a little bit more tender, it becomes a little bit elongated, and also it’s white. (62)

Etiolation keeps the asparagus from fixing, or creating, chlorophyll, which provides its green color. Etiolation means starving it of light. Is this what love is? Protecting something, keeping it from the light. Is that what makes it sweet and tender and precious?

So, is that it? Is that how we stave off the obscurity in which Dick Stryker perished, if we can? If so, then this is how we must do it, by this act of remembering, by this admission of our frailty, our precarity, by our refusal to bow down even though our fate may be the same as his. Even though, most likely, we will end up like him.

And yet, as we close the book we remember the narrator’s friend Zach and his story about his parents and the notes they leave for each other:

We’ll also probably find a bunch of little notes that my mother writes each year for our ‘Easter egg scavenger hunt,’ these meandering, stream-of-consciousness clues that are riddled with inside jokes and never point clearly to the hiding place, so she usually includes a parenthetical at the end that just says where to look. (27)

The fact is that these stories are not “meandering, stream-of-consciousness clues” because they do, each and every one of them, “point clearly to the hiding place.”

They do tell us “just where to look,” even if perhaps the narrator isn’t entirely convinced by the veracity of the stories being told to him. And so, we may turn from this book similarly uncertain: did all of this really happen? Has the author been stepping back and forth over that line, the line between fact and fiction? That certainly seems to be the case. Some of these stories, the ones he’s told, ones he tells us, possess that linear narrativity we associate with the recounting of dreams. And, of course, some, like Judith Malina’s, are indeed dreams retold. What is the author trying to tell us by stepping back and forth over that line? Is he making that familiar, conventional point that can be expressed in a number of different ways: that truth and fiction are arbitrary definitions, two sides of the same coin?

And by remembering Dick Stryker, for example, and all he was, and all he did, by creating a place for him, we create meaning and, perhaps, we find ourselves. In this world, maybe this is all we can ask for.

1. Steven Zultanski, Honestly (Toronto, Canada: Book*hug, 2018), 13.