'The government of love'

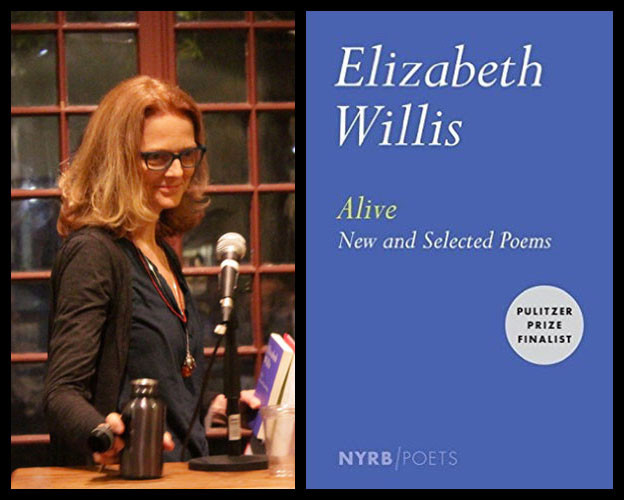

A review of Elizabeth Willis's 'Alive'

Alive: New and Selected Poems

Alive: New and Selected Poems

The speaker of “Survey,” a long poem among the “New and Uncollected” of Elizabeth Willis’s Alive: New and Selected Poems, illustrates public interest and personal exposure combining to make an American lyric. As the title suggests, the poem responds to an easily imagined questionnaire ranking priorities and concerns with a list of wishes and worries, two of perhaps the most private and maligned categories of our Just Do It culture in which both wishes and worries are judged as failures of will. While the typical survey asks participants to weigh the importance of a preselected menu of opinions and values, Willis’s goes off-road. Answers range from the civic concern of the opening lines, “No one uses the running path anymore / There’s nowhere to run to”[1]; to embarrassing private fears, “I worry that I will faint / where no one can hear me fall” (147); to the suspicion that “class / will follow us everywhere” (147). This worry that we will never shake socioeconomic hierarchies implicates democracy itself as a fragile myth sustained only by the hope that we all matter or can be made to matter. But just as “I/me” turns to and on the unimperious third party “us/we,” the fretful vision of civic decline changes to a reassertion of good fellow-feeling:

I think we all

need a vacation

I wish that I were an ocean-

ographer like my father

or the one he could have been

I wish that time could be

turned off like a machine

I hope eventually

we can speak freely

of everything (148)

Anticipating the poem’s conclusion, the empathetic recognition that we could all use a break recalls Ishmael’s philosophy of the “universal thump […] passed round.” Human authority hurts everybody at some point, physically or metaphysically, so we “should rub each other’s shoulder-blades, and be content.”[2] The speaker of “Survey” isn’t content, but the discontent impelling the wishes for what is not, and what could have been but wasn’t, swells the hope for what might still be, may very well be. If we can’t hit the snooze button on time itself, we can rethink time’s machinery and confront the now it’s always running in. In that extended now, we might relax enough to speak freely (not just protect freedom of speech) of everything, with our consciences and with each other.

The closing stanza of “Survey” turns again on its personal pronouns, from the “I/we” to the sweet intimacy of the “I/you,” the second-person designation so wonderfully the same for pluribus or unum:

I’d like to graduate

from the united states of plastic

I’d like to face the future

as if it were a person

I’d like to touch it

and still come home for dinner

I want to introduce you to my boat

I think that everything

can’t wait till tomorrow

I hope you’re awake

when I get there, that you’ll be

with me at the end (148)

As someone who has often bemoaned the lack of a tu/vous, du/sie distinction in American English, I’ve had a change of heart thanks to Willis’s exploitation of the second person’s elasticity, which seems now essential both to her lyric and the lyric’s characteristic properties of multiple address and intellectual-emotional complication. The continuum of the collective and individual, familiar and formal possibilities implicit in the “you” posited in these lines emphasizes Willis’s pervasive faith that personal connections and the quality of attention we give our everyday lives are the means to surviving (if not fixing) what’s wrong with “the united states of plastic.”

But this optimism isn’t passive; we can’t just wait out the problems. Arguably, it isn’t even optimism, but a leap of faith to envision a more humane, sane future for which there is little evidence. America’s vicious legacies, acknowledged most pointedly in “The Witch,” bequeath ample discouragement; however, Willis’s lyrics emphasize (and enact) compassionate relationships among strangers and the estranged made from enduring that universal thump. As the carefully broken lines hint, the end is sure while life and loyalty are not: “I hope […] / […] that you’ll be.” The gently reproving reminder that “everything / can’t wait till tomorrow” cautions that deliberate action, for the sake of our future, must be faced “as if it were a person,” with respect and kindness but also with efficiency and commitment. The future, like the present, is inevitably a common experience, as well as a common production. In the poem’s future, the speaker’s “hope [that] you’re awake / when I get [home]” extends the wish for an affectionate personal homecoming to the populace. In this move, the caretaking of private intimacy and domesticity seems symbiotic with the desire for a vital, plastic-free, nondisposable nation and homeland, something like the kinship of Whitman’s amative and adhesive love, and very like his ideal of democratic reciprocity and interdependency.

Willis, a scholar of the Romantics, calls Whitman’s unfulfilled prophecy that the United States is the greatest unfinished poem a “provocation” and “a dare”[3] for readers to transform themselves completely into that collective poem. Willis’s most recent poetry carries forth that burdensome expectation with the conviction that literature, especially poetry, has the power to bind a crowd of nonconformists into a creatively inspirited body politic.

Most pronounced in her poetry since the 2003 Turneresque, this faith in the lyric’s ability to forge and confirm associations has been a force, as Alive shows, throughout her poetry’s years of development. Marked by fragmentation and compression in earlier works like The Human Abstract, lineation becomes ambitiously varied, and form increasingly unpredictable: tight prose blocks give way to spare couplets, lines stretch to overtake the page in one poem, then gather tightly into the center in the next, as if retreating from the margins. Vacillation between sequencing and seriality accompany these variations, and lyric subjectivities unfold more visibly their intricate dimensions. Much longer poems distinguishing the “New and Uncollected Poems” shed the atmosphere of solitude pervading the poetry prior to Address. These new works sound more domestic yet explicitly oratorical, less protected and more coherently responsive to the meditative registers of everyday living. The imperative of a Selected Poems to gather together what’s been put asunder in monographs, which are typically partitioned into three to five sections, lets emerging readers see Willis’s range and established fans see that the lyric operations once accomplished across a collection are now effected in a single poem.

The final hope for a warm reunion in “Survey” highlights the prevalence of homes and homecomings, awaited and imagined, throughout Willis’s work. Her poetry connects physical dwellings with the homespun forms free speech has taken in the American idiom’s evolution: “let this house be Endeavor and build it” (3) from Second Law begins the collection, at once prophecy and command. “‘We build this house’ / and then we live in it” (43), from The Human Abstract, summons Thoreau’s handmade home at Walden and the imaginary mortgages taken out on his neighbors’ property. Like Thoreau’s supplementary fantasies, Willis’s lyrics urge reconsideration of the drive to own and fence in, endeavors that trap the owner and inhibit wandering, yet these poems also confront the material realities both necessary and unavoidable in actual living. The poem concluding the same sequence from The Human Abstract begins, “Against this house I always hammering” (44), to stress the violent aspects of self-making — the noise and impact — while also suggesting the individual labor contributing to a nationally shared home: we are still constructing, audibly, a place of belonging.

Willis’s poems hear this construction, this hammering out of deals and documents, in the unlikeliest yet most familiar interactions. The time-honored playground selection method rock paper scissors, which blends personal choice and chance, appears in two poems from Address. “Alabama,” a poem dedicated to shooting victim Maria Ragland Davis, indicates the selection game’s subtle violence by omitting “breaks” and “cuts” from its three zero-sum rules: “Paper covers anger / Rock covers flesh” (151). Under the surface of these innocent variations lies the obverse of fairness and its win-or-lose justice decided by metaphorical might. An equal chance at winning overtakes the democratic ideal of equal opportunity to participate, as the dangers attending freedom become its greatest expression. As the poem concludes, both paper and its coverage morph into a comment on the untrustworthiness of evidence and documentation, whether insurance policies or the protections journalism might provide:

In the end, as the ending

of a given or a proof

what you are or carried

can’t be covered, will be found (151)

Thus, even the benign conquest of “paper covers rock” insinuates that types of bureaucracy intended to confer protection and relief are merely whimsical barriers between help and no help, preserving another kind of quiet violence. In “Oil and Water,” the basic elements of the trio are revised in the line “Paper. Scissors. Water.” (153), which connects these less obvious dangers to the euphemistic metaphors so often in collusion with them, like “daisy cutters,” “oil spill,” or the personifications of hurricanes distracting from the people’s role in their destruction.

Importantly, no poem in Alive reduces the paradoxes of American discourses or ideals to one judgment or value. Instead, Willis’s lyrics settle into those paradoxes to illuminate their tensions and vitality. Her poems ripple with riddles and parables, astonishing combinations, both tender and confrontational. Particularly in poetry written for and after Turneresque, Willis advances the Thoreauvian precept “to reawaken and keep ourselves awake” (65). The sources and situations of active alertness in this poetry, however, are far more egalitarian than Thoreau’s, depending less on moments of quiet isolation than receptivity to and of language and those who use it. Willis has said, “Composition is a form of intimate congress with the phenomenal world, with other writers, and with everyday language acts.”[4] The participants in the “intimate congress” composing her poetry have multiplied with every collection, and count among them William Blake, Samson, Erasmus Darwin, B-movie characters, J. M. W. and Ted Turner, Emily Dickinson, and Lorine Niedecker; and language acts appear from everywhere, ranging from scriptural directives to driving directions, like those from the title poem of Address:

Turn left toward the mountain

Go straight until you see

the boat in the driveway

A little warmer, a little stickier

a little more like spring (121)

Blended in this tribute to this nearly lost art (thanks to the GPS) are the trust in another to guide you to a destination, the world made of landmarks and signs as it is experienced by the driver journeying for the first time, and the equation of that “intimate congress” of reunion and hospitality with natural cycles of renewal. Sticky matters, all, but generative commitments to put ourselves in another’s place — to see what he will see — and to put ourselves in another’s hands to guide us home.

Thoreau distinguished authentic, moral wakefulness from the unnatural excitement of artificial stimulants like tea, trashy novels, locomotive speed, and the stress created by the media. His solution to modern ills, in part, was to read in solitude the classics — not in English and certainly not in American English, but untranslated, in Greek or Latin, “for there is a memorable interval between the spoken and the written language, the language heard and the language read.”[5] The culmination of work represented in Alive remains awake to the channels among the high and classical and the low and populist; Willis’s lyrics live in that “memorable interval between” the ease and immediacy of speech and gesture and the concentration of unspoken textual contacts. They pleasure in the vocabulary of routine encounters that accompany deep wondering and wide wandering among the written and the spoken.

“Classified,” from 2011’s Address, speaks to the unsung forms of American currency and reads like a tribute to the innovative writing and thinking flourishing as the American idiom:

Will trade fountain pen for outboard motor

a trembling nightfall for government bonds

Will trade this grievance for a moment of silence

that wooded tavern for my aimless youth

Will trade potable water for loyal army

Fabergé egg for interpretation of dreams

Will trade heirloom lilacs for three cords of wood

Will trade this meadow for a person-sized piece of shade

Will trade fluttering leaf for a career in baseball (138)

Written in the lexicon of the local bulletin or circular, “Classified” registers one of those “intervals between” the written and spoken, contract and oratory, that makes a poetics from the American idiom and shows that it’s more than only slang or regional speech gone viral. Arranged so that “Will” stacks up against the left margin, “Classified” appeals to the eye as an invocation of community determination and foundational national givens (like Thomas Paine’s in Common Sense) that a generation is morally bound to bequeath a healthy nation to future generations, not waste time waiting out trouble. The internal near-signature (Will-is) further suggests the individual’s (and the poet’s) obligation, despite the I-lessness of the poem and most political agreements. To the ear, the anaphoric structure loudens the poetic claims of ordinary writing by ordinary people, whose familiar Trading Post shorthand conveys enduring mutual trust among citizens to deal fairly with one another; to believe, even a little bit, another’s word is good and we have something to offer, all in the interest of old-fashioned, anticapitalist commerce. The poem’s mixture of actual objects that might show up in the weekly classifieds, like fountain pens and outboard motors, with pastoral abstractions, luxury items, and personal situations celebrates the interesting accidents of trade as well as its triumph over newly manufactured needs and desires. “Connections between unconnected things are the unreal reality of poetry,” writes Susan Howe.[6] This poem demonstrates this “unreal reality” and Willis’s knack for coaxing beauty from bluntness among these intervals.

The classifieds and the grassroots circulation they perpetuate are antidotes to a culture encouraged to waste (the united states of plastic), but they are also an illustration of how provisional and varied value really is, despite the morbid reduction of almost everything to dollars in the loudest national language. In the middle of August, “a person-sized piece of shade” is worth far more than a sun-filled meadow, and what does anyone do with a Fabergé egg other than worry about breaking it? While anticapitalist in character, though, the poem isn’t antimaterialist: there is great satisfaction in material things, like fluttering leaves and wooded taverns, even (and perhaps especially) when they don’t belong to us or can’t be owned. A common fascination with baseball, whether for the outrageous salaries or sly pitchers, or with the annual surprises of falling leaves, helps people talk to each other and replenishes good will. To swap a pen for a motor, you’d probably have to meet the person who no longer wants the motor but has lots of fishing stories; those willing to exchange lilacs for wood quite possibly will share common appreciations, like warmth and flowers. Decisions to recycle, too, reveal changing interests and needs; sometimes we want to know what our dreams mean, and other times, we want something pretty to look at. Such changes of taste and heart needn’t become more trash, but new treasures, resolutions, or friendships. As much as he prized reading Homer in isolation, Thoreau’s love of imaginative bartering (also anticapitalist) included many happy chats with unliberated neighbors, and we see in Willis’s poem that there is still plenty of American intercourse that isn’t volatile or divisive. The poem’s final offer, “a wheelbarrow for an end to all that,” suggests our sense of abundant privilege doesn’t necessarily depend on excesses.

The wheelbarrow carries the poem beyond its ending, into the lyric interval between Thoreau’s imaginary wheelbarrow annually carrying off imaginary harvests and Williams’s rain-glazed red one upon which so much depends. The ebb and flow from rebellious independence to uniting dependency moves through our most recognizable literary allusions and among political and literary documents; the circulation itself is crucial to national self-imagining. In this expansive interval of interactive materials, Willis’s poetry emphasizes the ongoing interplay of literacies composing the American idiom. “Vernacular Architecture” articulates this mediation:

A governed love for the people

isn’t special

The government of love

is to believe itself unwritten

Love’s office is devotion

to the ungoverned, like justice

somewhere else, in a while

A school beside its architect

A child next to a picture

The family in its tunnels

Pure products feel their power

to feed the engine

Their movement a document

that totters into being (131)

Filled with understandings and expressions of who we are and where we live — a child’s drawing, the architect’s school, Hayden’s winter Sundays, Williams’s truth-telling Elsie — this poem, like so many of Willis’s, reminds us of our nation’s youthfulness and its constitution of unalike things and people still in progress. Families exiled and oppressed by the Old World and those born in but still tunneling toward liberty in the New join the “pure products” whose only power is their claim to purity. In this early interval, a government founded on love and the ungoverned in need of it (as in “radicals” and “the voiceless”) is still tottering into being. In other poems, the governed and government components of the body politic also advance like children crawling, uttering “nonsense syllable[s]” (55), but, as here, they are learning the movement of a living document.

In Turnersque, “Sonnet” echoes the Pledge of Allegiance to consider the centrality of public education to that movement fueled by desire for liberty and “justice,” still “somewhere else, in a while”:

Thinking through

a desperate wedge

of indivisible ink

we fall in filaments

an uncontrolled breeze (54)

The familiar recitation first learned along with reading and writing in school, the Pledge has frequently been a “desperate wedge” between church and state, a point of contest between personal liberty and public good. It is also, the poem suggests, the invisible ink of the social contract to pursue its ultimate goals of “liberty and justice for all” and to think through desperate times as “one nation, indivisible.” As a series, “Sonnet” turns attention to the dimensions of the schoolroom lost in the unanimous contempt for No Child Left Behind:

The teacher’s love

of someone’s children

a flash of light

in white air

So loving love

we lack science

and in ourselves

touch up the little

teacher’s picture (53)

In elementary school, we learn to speak together and to take turns speaking, as many and as one. The teacher who governs other people’s children with love is Willis’s metonymy for a calling: the vocation is as unscientific and unreasonable as they come, but the pursuit of happiness was always meant to be the pursuit of meaningful labor, the freedom to answer any call. The teacher sees “the green, braided thing […] / inside you” (52) and spends a lifetime emboldening pupils to picture its unfurling. “Alive,” the penultimate poem of the book (followed, necessarily, by the elegant “About the Author”), concludes by imagining America’s most potent symbol as a student waiting to be called on:

See that woman in the harbor, her sandals full of sea-

weed? She knows she’s going under.

She has a question. She’s raising her hand. (180)

Sinking under her symbolic weight and the encroachment of climate change, Lady Liberty becomes a powerful emblem of dissent — a sign and a dare to question, with love and with courage, those who govern, the ungoverned, and the governed, even and especially when we, the people, know we’re losing.

1. Elizabeth Willis, Alive: New and Selected Poems (New York: New York Review of Books, 2015), 145.

2. Herman Melville, Moby-Dick, 2nd ed., ed. Hershel Parker and Harrison Hayford (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2002), 21.

3. Elizabeth Willis, “Bright Ellipses: The Botanic Garden, Meteoric Flowers, and Leaves of Grass,” in Active Romanticism, ed. Julie Carr and Jeffrey C. Robinson (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2015), 30.

5. Henry David Thoreau, Walden and Civil Disobedience (New York: New American Library, 1980), 72–73).

6. Susan Howe, My Emily Dickinson (Berkeley: North Atlantic Books, 1985), 97.