Golden

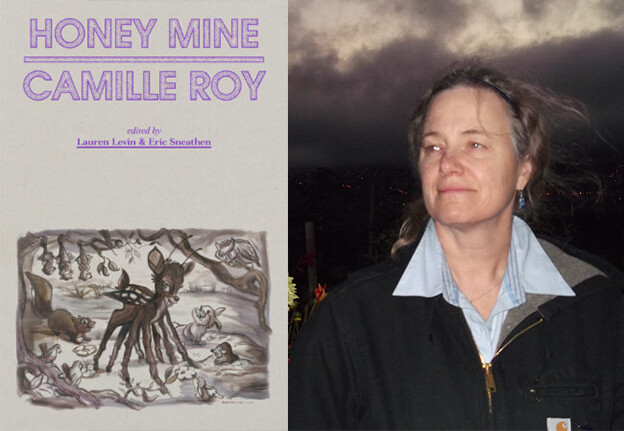

Camille Roy's 'Honey Mine'

Honey Mine

Honey Mine

Among lesbians the story is a form of sex talk — a joint whereby the community and the couple are of the same body (155)

Beautifully edited and with a smart and contextualizing introduction by the editors Lauren Levin and Eric Sneathen, Honey Mine gathers new and collected work from the last thirty years and includes a fresh afterword on Camille Roy’s prose. Roy’s previous publications include, among other things: Cold Heaven (O Books, 1993), The Rosy Medallions (Kelsey Street, 1995), Cheap Speech (Leroy, 2002), and Sherwood Forest (FuturePoem, 2011). The title of this new collection tells the reader a lot: Honey Mine. Honey, that viscous product of the hive, both nutrient and excess, sweet and sticky. Mine — the possessive pronoun and noun, as in gold mine. The word order — slightly aslant. Not My Honey, but Honey, first and foremost, and then Mine. Mellifluous, intriguing. Full of pleasure. Full of ore.

And so it is, this text, rife with pleasures. It is intimate too, beginning with the Agatha letters, addressed to the eponymous but mysterious “Agatha.” In these letters, Camille, the character, wonders: “Is it all point of view? Pleasure, I mean — the surprise in the dark.”[1] The writer ponders the question, asserting, “I suppose it’s different for everyone. To Camille it felt empty and fresh, because she was.” Throughout the stories and experiments Roy pursues in this collection, many from a young person’s point of view, the reader is both invited inside and kept a little at bay, by which I mean: opacity is a virtue. A “surprise in the dark” might occur anywhere.

Honey Mine’s material is capacious, messy, fluid: “nubs of dread sprouted on the broad fields of my tongue” (209); “my beloved was a strong woman with small breasts and a sensual roll in her walk. Skin so soft it would yield to any touch, then foam back and enclose it” (188); “The leaf world whitely barking. And cottonwood by water yessing like her little boy as he mouths a thistle’s purple bud” (187). As Roy writes in “Under Grid,” “the writing [she] prefer[s] is packed with sensation, relation, insight” (303). The pieces in Honey Mine frequently turn on and simultaneously reveal the invisible becoming visible — whether class or sexual or racial divisions and codes, the workings of desire and power — like some pebble breaking the surface of a pond, its rings radiating outward, and then disappearing. Below the surface, the water is teeming; light flashes; the shadows are deep.

Roy lets us in on a secret. We hold some things in common and others not:

This story is coming from brain tissue, and that makes it alien and intimate, even to me.

But I’m writing it, and that means I’m taking experience through the fake death which follows artificial life. To me, writing doesn’t feel like an act of the imagination. It’s more like the sedimentary traces of that act, a kind of cleaning up after the fact. (11)

All stories come from “brain tissue,” and thus are both “alien and intimate,” though not everyone might see it that way or imagines writing as “cleaning up after the fact.”

Honey Mine willingly exposes the messy and constructed text, like so many works of New Narrative’s gay, lesbian, and queer writers who emerged in the late ’70s in the San Francisco Bay area (that spicy cauldron of literary scenes including Language writing, movement writing, and queer performance). Roy’s writing and characters, including Camille, are grounded in realism, in a history of her times: that is, in things that are vitally true if not always factually so. And the language is hot:

Camille. The name feels like an accident repeating itself through this story, even as the girl attached to me through that name remains somehow indecipherable. … It’s true that I erase and embellish and even lie in everything I write about her, but I don’t think she would mind. (17)

and

Of course I’ve never told a story straight in my life (and in this essay, I haven’t tried). This is not hypocrisy, because consistency is not my point. I’m a seamstress of blur, performing nips and tucks on the empty center. (128)

Honey Mine is an archive of feeling and experience; despite Roy’s assertion that she’s never written a coming-out story, Honey Mine offers its readers a sweet entanglement of story, essay, and poetry that traces Camille’s collision with and discovery of the worlds around her — from the Southside of Chicago to a Rocky Mountain mining town where Mina Loy is in residence, to a massage parlor in Michigan, then to San Francisco. Roy’s writing goes where mainstream fiction cannot: “the well-modulated distance of mainstream fiction not only distances social conflict, it also doesn’t represent lesbian relationships very well” (241).

There are commie parents and their silences — “My parents met at a C.P. meeting. That’s all I know. I never heard what they said to or thought of each other. No personal touches. Somehow that didn’t qualify as ‘material.’ (Is this a Marxist definition of material?)” (129) — and racial divisions — “Monica was black in a segregated city; so the closer we got the more transparent I became, my longing vicious as wavering lights of association. Relation — the spot where we’re the same, or at least rolling downhill on a boulevard lined with palm trees and novelty shops” (98). And there’s the clash of class, Camille’s family a mix of ruling class and low: in “Craquer: An Essay on Class Struggle,” the narrator asserts, “The class codes become visible, but that’s hardly comforting. There’s nothing homey about a set of rules. They were there before I inadvertently broke them, and they’re still there” (148).

Young Camille finds herself hailed “Hey faggot” (36), wondering, “Fag, no way, I told myself. What does that mean anyhow for a girl?” (38). Honey Mine circles language and its secrets, signs and their interpretation, the narrator in “Isher House” reveling in the “little gang[s] in [her] life” (76) and later in a variety of late twentieth-century lesbian communities opaque to the mainstream, sweet underground hives for those in shelter. After all, “survival is a collective accomplishment,” Roy writes in the afterword (326). The mainstream casts — how could it not — its shadow over this book. The threat and very real experience of violence hangs in the air, as Roy puts it: “Being a lesbian meant living at the edge of a disastrous and threatening form of visibility. Recognition could turn to violence in an instant although mostly there was erasure and absolute zero cultural capital” (320).

Language has the power to cast dangerous, but also protective and erotically charged, spells. Threatened by a strange man who exposes his cock in the story “Isher,” Camille summons the word “dyke”: “This won’t work cause I am a dyke. That’s a fucking big word. Dyke. I hadn’t known that. I discovered it that day” (67). A version of this story appeared in Roy’s early 1990s play Bye Bye Brunhilde in which a lesbian character named FEAR claims to have been hitchhiking and picked up by Ted Bundy. FEAR says, “I look up to see his mouth twisted up like a rag, his face looks like my death. And some weird shit is coming out of his mouth, girlfriend. My head opened a crack and I said the first thing that dropped into it: This won’t work because I am a LESBIAN.”[2] After the encounter in “Isher,” Camille, thinking about a lover, writes: “In the future I was going to call Isabelle. What would I say? The word dyke, of course. Dyke dyke dyke. Perhaps I’d mention the hot and friendly feeling which was spiking my chest. It was about weaponry” (68). When Pearl, Camille’s mother, comes to pick her up at the end of her summer in the midwest, Camille’s ready to go, equipped with experiences and embodied knowledge of language as epithet turned Medusa’s shield, secret, and sexy: “My head was a blur of monster words: faggot-pussy-dyke. They had a shimmer and a slickness as I held them back in my throat. It felt better than a secret” (69).

A word of caution: though this text tells the reader that Camille is sometimes a character Roy identifies with, and others, a flimsy ghost, the pieces in this collection will slip the rug out from under if you get too comfortable and assume that Camille and Roy are simply one. In “My X Story” the narrator declares: “I was there when Camille, a neighbor, bought a stereo and speakers from me for 75 bucks” (111). Authorship, storytelling, and character are far more complex. In “Craquer,” the narrator is confronted by her cousin Sam who objects to the way he has been portrayed in her writing.

I objected but mildly. I sipped my tea. After he left, I found myself stewing, then I began a strenuous argument in my head. It boiled down to this — if I’m the only one with the appetite to tell a story, it must belong to me. I do the work. It comes down to my appetite, which in turn comes down to whatever grips my powers of recognition. That’s what makes my little engine purr. I take the facts and expand along lines of thrill, aiming for unreliability, its quivering heart. (116)

And:

The urge to aestheticize, to edit and invent, is my urge to think. There’s inescapable falsity in my condition. If you believe what I write, watch your back. (123–24)

Honey Mine is a book steeped in time and the particularities of its communities. Roy’s afterword reiterates the book’s specificity: “It’s vexing to use words, particularly when their meaning has changed. It requires such a high level of care” (319). Roy writes, “Sometimes I feel that the truest respect one can show towards the past is to allow it to be something other than predecessor of the present” (319). It is the capaciousness of Roy’s canvas, the scope of her explorations, her way with language, her tense tightrope walk along exposure and revelation and artifice and withholding, that are among the many things that makes reading Roy a pleasure. And this book is a page-turner, though not in the classical sense of plot-driven books. Rather, the writing is a palpable flickering lick of an all-but-vanished way of living, rich in specificity, the liveness of language strung on the lure of surprise, moved by the swerve from and resistance to conventional norms, refusing to expose it all. Opacity and the flash of flesh work together. The hall of mirrors that Roy makes of proper nouns — Camille appearing and disappearing, intersecting with the “facts” of Roy’s biography, her penchant for realism (though, again, not classical realism per se, but an embodied and truthful storytelling), her paean to the pleasures of a lesbian underground, of a band of girls, of the swerve of a word or phrase — these are generously on offer to all who may wish to enter.

Maybe the kind of veering stories-that-are-essays-and-sometimes-poems in this collection comprise not a coming out but a divine diving in and going under, turning over; there’s so much ore, golden:

Lately I’ve been thinking that I am a wave, and all the stories in the world are the water. I’m among stories, just like all the other waves. Which part of the water belongs to which wave doesn’t actually matter. It doesn’t apply. Personally, this means I can’t fall apart without changing into something else, other stories, different ones. This finds a solution in dissolution. Somehow it relaxes me. (150)

1. Camille Roy, Honey Mine, ed. Eric Sneathen and Lauren Levin (New York: Nightboat, 2021), 9.

2. Camille Roy, Cold Heaven (Oakland, CA: O Books, 1993), 11–12.