'As a friend seated beside the poet'

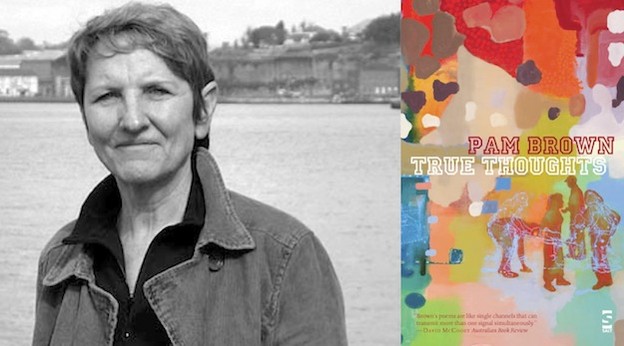

A review of Pam Brown's 'True Thoughts'

True Thoughts

True Thoughts

The title of its first poem, “Existence,” signals that True Thoughts may be aiming for the high rarified light of metaphysics, but Pam Brown’s version of existence links a series of lived moments delicately by chance, proximity, irony and imaginative association, such that existence is this embodied bricolage of moments arriving obliquely at the unhurried pace of living. Brown’s embodied fragments render a texture which is accretive rather than dramatic, and paratactic rather than metaphoric, though at any moment “ready to blur / into a field of speed … [as] one less path / to torpor.”

Suspicious of rhetoric, these poems don’t avoid its use but render it harmless by revealing its mechanism — by showing the hinges of its operation. This builds trust between poet and reader, as the poems wryly comment on the method of their making, which is on one level transparent, but by no means simple. With haiku-like poignancy and brevity, the lived moments traverse multiple registers of self-awareness, observation, social critique, and literary memory, including sudden brutal humor:

war

is

imminent,

Sydney goes sailing

Indeed, war is ever present as background noise, and Brown is ever aware of an Australian middle class indifference, as long as the sun sheds sparks over the sea. Brown’s artistic eye claims for poetry a plethora of “unpoetic” materials, such as radio wheeze, text messages, Blockbuster, Google, commercial fonts and cooking shows on TV: “the kitchen man / agrees / it’s all about oil,” yet here the “all about oil” doubles as the reason for war, as both monetary plunder and the lubricant of economy and media. This kind of layering of meanings describes much of the action in Brown’s poems, as the ordinary surfaces of the day radiate messages prismatically, even as they resist symbolism in favor of an embodied materiality in pastiche.

The book’s second poem, “Amnesiac recoveries,” comments on war and this new kind of war media, which turns destruction into a business of entertainment, as a holocaust of national collective memory in the bombing of Iraq’s ancient library generates new memories for a distantly safe TV-watching audience:

I know the war continues

on tv

in the background of the frame

the investigator yawns.

…

memoricide —

bombing the library.

collective memory,

the treasures of manuscript,

…

the bombing filmed

…

as I write as you read!

the USA

is bombing

______ ______ ______

(please fill in the blank spaces)

The poet and reader are held accountable for complacency (or merely powerlessness), and the fill-in-the-blank predicts that the bombing will go on, that fifty years from now a new generation of readers will be able to fill in the names of the current victims of America’s endless war. The “as you read” is ironically measured against, though distantly, Denise Levertov’s poem “To the Reader,” wherein “as you read / the sea is turning its dark pages.” Levertov’s absorptive image may hint at the turnings of history, but its mythic grounding provides a comfortably theoretical space for the reader. Brown creates a different effect, where the reader is hurled through a window toward “turrurrism // war on turrurrism cramped / by cost bungling.” Brown’s aping of George W’s pretend-to-be-Texas drawl is hilarious and even more so, perhaps, for an American reader, yet at the same time the power behind this idiotic neocon is terrifying. As is Australia’s response to Bush’s war:

we rally for peace

we play with the kids

the armada heads for the gulf

But this book is not about war as much as it’s about living. Or better said, it’s not about living, it is living, neither a dramatic enactment nor a referent, but the thing itself. Brown’s lived spaces link naturally and horizontally without the imposed vertical arc of Aristotelian drama. In reading, one passes time with the poems, in the poems, and comes increasingly to trust and to like this poet, whether she’s listening to punk music, waiting for a bus, making tea or reading Samuel Beckett. In “Death by droning” we are given Brown’s not-autobiography. She compares her method to what memoir is not, a droning on, “I couldn’t write a memoir / to save myself.” Rather than linear biographical progression, Brown’s poems adumbrate the traceries of mind, which, among her political insights and lyric moments, include the daily, even bored, material of work-thoughts — and from this a life does come into view:

droning on is not

my way,

mine’s more a kind of

devolution

or maybe,

simply, to make art

through spaces

Brown’s not-autobiography collages poems that think on the page, often as notes passed from self to self through some internal space neither wholly private nor meant for the public. We don’t so much overhear them as an unintended audience but hear them as the speaker hears them, still inside the self, intimately bound to the thinking in which they float.

seems like Brisbane

summer grey

and I’ve come so very far

to make this small comparison

This commentary is self-derisive, and self-directed, yet, once more, we overhear it not as a reading public, but from some privileged inwardness, or at the very least as a friend seated beside the poet. A remarkably intimate experience, not autobiography but auto-intimacy. This, then, is where the title True Thoughts earns its authenticity, a title so literal as to be ironic. The “truth” behind these thoughts is entirely subjective, and in making no claims beyond this lens, such thoughts are irrefutably genuine, and the experience of reading them is fresh and rewarding. Here, in the hands of an artist, subjectivity is not a weakness, but the very basis of intimacy, of honesty. Likewise, from the subjectively human experience, a new kind of nature-in-the-city materializes: Brown’s poems, whether in Australia or Europe, are committed to the cycles and bric-a-brac of urbanity, yet one which allows for calm and beauty, as of an urban pastoral:

all afternoon in a car

parked at the ferry wharf

gazing at sparkling waves,

not reading

not listening to the car radio,

just looking out at the boats

and the sea planes setting off

and returning

These seaplanes seem as natural as migrating geese, their small circling replacing the seasonal cycles in a new rhythm entirely of our own making.

The poem “In europe” takes this reversal one step further:

a bird flock swarms

in folds & turns,

in geometric patterns

like a screen saver.

Here Brown’s brilliant reverse metaphor, the “screen saver,” is afforded a priori status, yielding primacy to the simulacrum, the signified pointing backwards, bemused, toward the sign. Even as Brown takes pleasure in this reversal, the poem is asking how we can stop the war and ecological disaster when the culture has lost its connection to the real, to any natural point of reference. In the poem “Darkenings” Brown sketches a scene of going camping in which the natural darkness is non-normative, a disruption of the natural order of the light bulb: “you go on vacation / to an unmodified landscape, / towards a blackout / the cause impossible to source.” Yet, Brown remains an alert naturalist, and her urban spaces are deeply observed for those species that share in them:

it’s October so

the bogong moths

are back

and the koels — the October

crack of dawn racket —

are back again too,

mauve jacaranda petals

are stuck

on the window screen wipers rubber

A large portion of True Thoughts takes place in Rome where Brown is living in residency. In another reversal she playfully positions this adventure as an exile from Australia, “remote, / yet, / in touch!” — far away, even as she resides in the center of the old empire, a wonderful irony, and again a profound subjectivity, to be exiled to the center! Despite Europe’s eccentric pleasures, one gets the sense that Brown would rather be back home. All that remains in “No action” is to “join a group to / combat complacency.”

Brown’s sophisticated wit and honesty resist easy lyricism, yet there are several places in the book where Brown artfully navigates between quotidian and lyric spaces, as in the poem “Lab face” where the soul finds its footing in the food court:

heavenly shades of night

are falling it’s twilight time,

thinking outside the tick box

on the last day of the past,

to ready my selves

for an inurement of toil

I’m sauntering over

to a cheap eats turn

at the food court,

The plural “selves” reinforces the book’s collage effect, as if identity is at best a momentary phenomenon, the self moving among selves as temporary frames, as the mind fills and empties of sensory experience, of memory and cognition. From there the poem swings into the elegiac, yet at once we recognize this has been a tone present all along, the struggle against helplessness and inertia felt throughout are merely the precursors to mortality:

but later, tonight,

knowing this is the last century

of which I’ll partake,

(my lassitude,

my dis-belief, and

mon dieu, my grief)

I’ll lie on the laboratory couch

(I’m looking forward to it too)

We might hear the distant sound of Prufrock’s “I grow old … I grow old … / I shall wear the bottom of my trousers rolled,” yet Brown’s self-elegy is undecorated and entirely convincing, as here: “my eyes ringed / and sagging, / like a beagle’s eyes.” A more apt comparison can be made to Woolf’s Dalloway, as Pam Brown is a Flaneuse, a wanderer through urban and intellectual spaces of which she is a product — a flaneusing of mind, of which we partake intimately. Her inquiries range widely from public to private, through humor, irony, outrage, and surrender, asking, “how shall we live?” and (dare I say it) “how can we be happy?” — yet it’s this elegiac tone that leaves the most lasting impression, a paradox of revelation and helplessness — as in, “I know how to fix everything / but, / obstinate in my resolve, / withdraw.” This self-awareness proposes a terrible irony which blurs the boundary between a politics of resistance and a mere personal exhaustion, a space in which many of us middle class (or culture class) progressives find ourselves. For this reader, Brown’s inquiry and her art are entirely satisfying and necessary.