Europe's shadows vs. America's dreams

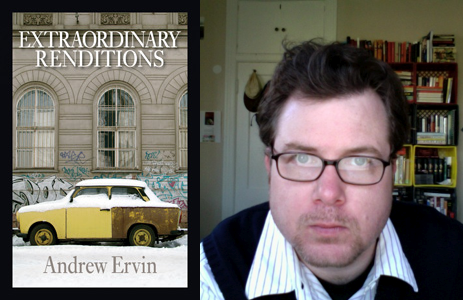

A review of Andrew Ervin's 'Extraordinary Renditions'

Extraordinary Renditions

Extraordinary Renditions

What amazed me most about Hungary is that history is not history there. The events of the past are still present every single day, at every minute, in ways I couldn’t even imagine at first. — Andrew Ervin, Press Release

Europe. It’s impossible to underestimate its allure. And equally impossible to measure the influence of this continent’s history and power on countries like the United States of America. Andrew Ervin’s debut novel Extraordinary Renditions is set in contemporary Budapest, the capital of Hungary. A country that has experienced the glorious highs of classical Europe and the worst of late twentieth century savagery, political intrigue and Cold War disaffection. Extraordinary Renditions is both a homage to this very European country and a journey into history that ultimately sheds more light on contemporary America than on contemporary Europe.

This novel takes its place in the rich “American voyagers in Europe genre.” This genre is a product of America’s fascination with the culture and history of Europe and an attempt to wrest away the best qualities from the old world and revive the uniquely American dream. Ervin is a strong writer in awe of Europe. His novel is immeasurably bettered by the fact that he lived in Budapest for many years and knows its streets and architecture, its moods, and its history intimately.

In this challenging period in America’s history, when America must redefine itself and its position on the world stage, Ervin presents us with the stories of three original characters whose stories are linked by situational coincidences in the narrative: the émigré, the American soldier and the young musician.

In “14 Bagatelles,” (the title is taken from, arguably, Hungary’s greatest composer Béla Bartók’s piano piece “14 Bagatelles, Op. 6”) the first story in this trio of connected stories, a world renowned composer, Harkályi, returns to his birthplace for the first production of his opera The Golden Lotus.

Harkályi was a young Jewish music prodigy when World War II erupted into his personal world. He survived the war largely thanks to his musical ability and the love and insight of his mentor Zoltán Kodály. Harkályi left his family and fled Hungary for the relative safety of America: the safe harbour for many of Europe’s wounded, disposed and displaced after the war.

Portraying a Holocaust survivor is no easy task but Ervin does so sympathetically and concisely. Providing just enough insight into the day-to-day horrors of life lived in captivity and the rare moments when joy invaded the camp thanks to the musicians and their passion. As Harkályi walks the alternatively familiar and garishly foreign streets, we see the composer as a young man in a concentration camp and as an adult in self-imposed isolation within the inner world of music and notation and spaces between notes. He is estranged from the country of his birth and estranged from his religion. While in the camp he invented a novel system of musical notation. One that preserved the musical history of his culture and country and one that was sufficiently flexible and expansive to change and recreate itself as the composer grew, matured and reinvented himself in America.

It is a smart piece of plotting to bring Harkályi back to Budapest for the first performance of his opera The Golden Lotus. The performance of this opera does indeed provide a stupendous climax to the novel. Ervin employs another structural device whereby all three stories are linked in time and space. The story is set during Independence Day celebrations in Budapest. This works as a structural device, but it’s rather labored and by the end, polemical in a distracting fashion. However, this device can be used subtly and unobtrusively. I think of two recent examples: Night Train to Lisbon by Pascal Mercier and Nicole Krauss’s latest novel Great House.

The novel is open to criticism that it is three thematically linked novellas rather than a novel in the traditional sense but I don’t see any merit in this argument. Ervin’s novel is a further contribution to this genre whose formally strict structure is constantly evolving. However, for his future novels, I hope Ervin pays closer attention to the subtleties of plot and dramatic devices.

Ervin is profoundly sensitive to music and exceptionally talented in translating into words the sensations and mechanisms of musical notes. So it is no surprise that like a jazz musician doffing his cap to the progenitors of his religion, Ervin evokes the spirit of Kafka. Another beloved son of the region, Kafka was born in Prague, Bohemia, which was then part of the great Austro-Hungarian Empire. Kafka’s prose style and philosophy is evidenced in the very strong chapter “Brooking the Devil.”

There is more than a touch of the desperate film noir thriller in the powerful and poignant story of Private First Class Jonathan “Brutus” Gibson of the United States Army: African American, accidental soldier, philosopher, poet, outsider, loner. Ervin analytically exposes a morally and criminally corrupt US Army culture that has been exported to Hungary and the world in the name of protecting freedom and fighting the “war on terror.”

Along with Levi’s, Marlboro cowboys, Coca Cola, and McDonald’s, to name a few, the American Army has been sold to the world as the pure and true deterrent to the opponents of democracy as it has evolved in Euro-influenced countries. America has always been a country of exceptional salesmen and women. A land where a ponderously named lad called Samuel Langhorne Clemens reinvented himself into the great and iconic Mark Twain. Ervin successfully juxtaposes images of savage bloodletting from WWII with the equally hideous modern devices from the so-called War on Terror.

Sergeant Brutus, with a nickname that evokes the classical elegance and wisdom of Shakespeare, and a patter that reads more Bronx gangster than Philadelphia brother to this non-American ear is marooned in Hungary. An intelligent young man seduced by Army recruiters spruiking freedom, solidarity, money, nobility and a pass to college. In eloquent passages, Brutus details the many ways in which Uncle Sam has proved to be another incarnation of “the Man”: the oppressive, dangerous and irrational racism that pervades American history, politics and culture.

The soldiers are outsiders but not resistance fighters, and cliques abound: whites only, officers only, and so on. Brutus’s experiences are graphic examples of the penalties for standing out in the “vanilla crowd.” Difference is celebrated in sound bites in most democratic and liberal countries but a black, articulate and intelligent man is doomed within the enormous machinery of the American military. The American military’s own mythology and its romanticism by Hollywood usually ignore the stark, brutal and vile abuses of power and desecration of personal dignity and humanity that are committed in the interests of “keeping the peace,” or in this epoch, “wining the war on terror.”

Brutus is the innocent young American abroad who is plunged into a Kafkaesque nightmare. Brutus’s descent into a maelstrom brings out some of Ervin’s best prose: a combination of contemporary American gangster rap and descriptions of Budapest that powerfully evoke the Cold War.

In ‘The Empty Chairs” we meet the final character in Ervin’s triumvirate. Melanie Scholes: violinist, American, young, bisexual, white, outsider/loner, and the novel’s only genuine spark of hope that a fulfilling and generous future is possible.

Although this is probably the weakest of Ervin’s “renditions” (it is obvious that Ervin named his novel after the legal term for the systematic abduction and extrajudicial transfer of persons from one nation to another, but I prefer to think of his characters as renditions, powerful reimaginings of classic tales) it concludes the novel with a pièce de résistance of timing, evocation and prose mastery.

Melanie is one of the musicians tasked with performing Harkályi’s new opera, The Golden Lotus. In a quicksilver night/day of her life, we meet her lover and glimpse their claustrophobic and pointless affair. She is a vexed artist, drifting aimlessly in Budapest’s monochrome world of émigrés and disaffected affluent American youth.

In a masterful and controlled example of character exposition, Melanie evolves from an uninteresting and pathetic figure into the unlikely heroine of the novel. Freed from her inertia by the ecstasy of music and her hitherto dormant ability to reinterpret and transform musical nuance and notation, she explodes orthodoxy and convention in a powerful scene in which the past and future are welded together in the revolutionary power of music to be beautiful whilst uniting people irrespective of color, creed and nationality.

Ervin has written a powerful and sophisticated meditation on identity, nationalism and personal responsibility. Memorable characters and icons: composer, soldier, and musician they are a glimpse into the darkest of human capabilities and the possibility of redemption, however remote. Ervin is a very promising young writer — a uniquely, American writer.