The enlightenment of bushes and grasses

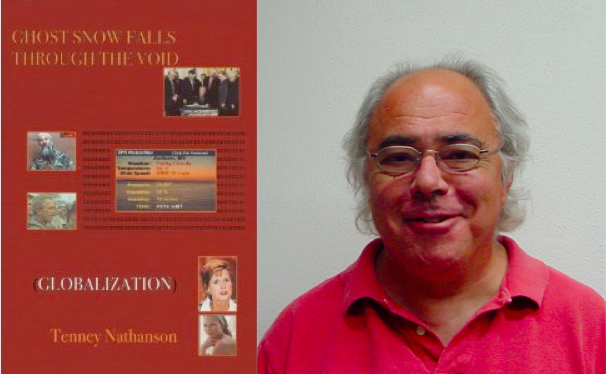

A review of 'Ghost Snow Falls Through The Void (Globalization)'

Ghost Snow Fall Through The Void (Globalization)

Ghost Snow Fall Through The Void (Globalization)

In Tenney Nathanson’s most recent work, a practice of intertextual poetics is exacted as a form of revenge upon the stupidity of recent American history. That is, with an arsenal of acquired “inarticulateness” and aphoristic sign-offs, Nathanson deals with the war, the economy, and our impending doom. Through the course of the book, Nathanson continues throwing himself against news stories, narratives that stupefy. Yet he manages to return to some degree of sanity, balanced between Zen practice and the pleasures of the American poetry he both teaches and torques over the course of this book. Notables include William Carlos Williams, Crane, Dickinson, Whitman, Frost, and Whalen, among others. Nathanson’s face began cracking open in “Home on the Range” and it has not stopped (“I’m Rilke now my face cracks flows and morphs”).

The book reads as a diary of reactions to the news of the last decade. Nathanson’s treatment of his source material feels singular in his quotation and grafting of the news into the American literary canon, a feat he repeatedly achieves to work up a wry commentary of subjects like air pollution in New York after 9/11 and how Whitman might respond to the situation.

“[N]ot addicted to a foolish consistency” arrives as a phrase that succinctly communicates Nathanson’s relationship to his source texts. The book balances on this statement, particularly when covering election night, admiring the Obamas on stage while simultaneously mulling over our country’s economic prospects. Agony and ecstasy share the same breath as Tenney Dickinson breaks in over the radio:

a gap making the air softer

Than Oars divide the Ocean,

Too silver for a seam —

I’m not sure where the dashes go

or the butterflies, or banks of flowers at noon is that what it means

they have all gone into the what?”

Impersonation counterpunched and opening into a florid metaphysic, unashamed stylistic wandering through brambles of medi(uh)age. This poem contemplates its nows, zigzagging in and out of literature past and present (“pour a wind / that can learn to forget”) into our present state of alarm (“the closest the president will ever get to saying / with his helmet tucked under his arm / “‘of course I like it’”).

Ghost Snow is a demonstration, a true glug-a-thon, where the glugs are ticking and tracking the dumb dumb dumbing Americano political scene and mediascape. Nathanson reveals himself huffing hatred guised as political commentary and it’s enough to send even pacific Tenney (he who worries about the appearance of brandishing a squirt bottle at a pet kitty) into a blind rage before quieting down (“let it go,” he says under his breath), coming to rest on scaffolding built by Hart Crane (“adagio of islands … bind us in time”), and granting himself a reprieve from neocons.

And then Emily Dickinson is introduced to child slavery. Whether it’s Tenney Dickinson or Emily herself floating through the news, it’s so good. I don’t care if it’s her double. That is, chainmail immediately precedes supply chain politics and prepares us for

I offer the Gods

this Carmen Miranda banana hat for the void

yours truly United Fruit

Nathanson manages to show us the last 5 years in American history at the very moment it filters through him so that we are not reading Tenney ex post facto but as he is receiving the news:

In the Tenney mirror the alienation drops quickly into a weighty sadness, a

diffusing tenderness like an old familiar wound, then nothing at all,

even the what is that heart that still sees them in the dark dropped

drowsing

into the big no pool

Moved then mostly scared as I am welcomed by Nathanson into the “commodious vicus of recirculation,” scared because of what it portends for our ability to read with any sense of where or when. Welcome to the age of search terms, living off the soggy phrasing of Newt Gingrich’s bomb of a novel (1945) and lightly passing over Iraq’s cultural disintegration. The interruptions separate this book from other poetries attempting to hold the same discussion. Nathanson dubs the problem “the overstaid fraction.” And so the interweaving goes on and on: Sonoran desert, Iraqi desert, and the UA Modern Languages bathroom and voila, the fraction vacates a little into Tenney Freud’s floaty time.

I don’t think Nathanson a.k.a. “my personal ratchets are in pretty good working order” is particularly worried about holding the reader’s attention. The book isn’t a crowd pleaser. The book is a crowd. Nathanson’s setups and breakaways are not pranks. Whomp. More like preservatives, so that his ruminations on the fate of American culture don’t stiffen up too quickly. Nathanson’s enemy is rigor mortis, and he knows how to wiggle out of that without forgetting what he’s saying (I’m just saying). Nathanson teaches imitation to his poetry students, and this book surges through imitations, set up by the question, “What is the character for Tenney?” It could be Tenney O’Hara breaking the tedium of the day with a glass of papaya juice and back to work. Or Tenney Bush: “I am the country’s first MBA President.” Tenney Frost and Tenney Crane are pretty good too.

That’s the high stuff, the pyrotechnics. In between explosions, there’s silencio tucked into the poem, with sentences like “the palm tree clattering shaking loose its birds, skeining away toward the mountain like gum.” A set of folds enlivens this writing practice fused together by an attention that’s diffuse and buzzing (“thinking splayed out like a Chinese scroll made of mud”). The word of the day is panoramic. Yes. And absurd and tender and incisive, as the book goes tromping and transgressing through our idiocracy to find out where the evil of the year goes (thanks Tenney).