'The Emptiness You Seek Also Takes Time'

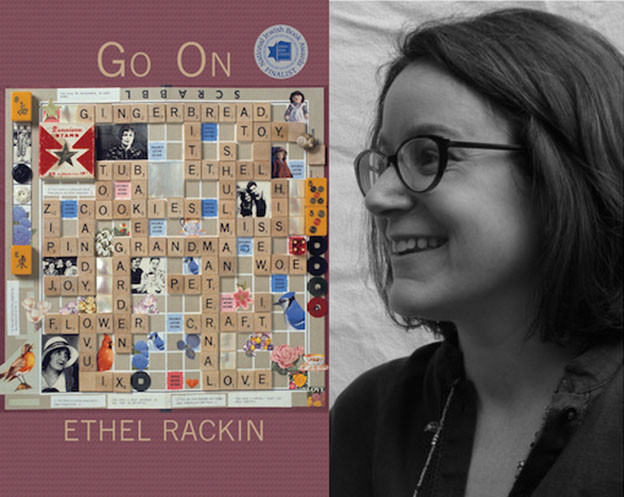

'Go On' by Ethel Rackin

Go On

Go On

Jueds: “[T]he emptiness you seek also takes time,”[1] the speaker of Ethel Rackin’s strange, magical, and luminous second book tells us at the end of the title poem. The poems in Go On are mostly small — the briefest a single line — and yet they do take time, deep, mysterious, and wide-ranging as they are, to truly enter: they are enormous within their brevity. And, following from Rackin’s Buddhist sensibility, the poems do seek some sort of “emptiness,” which could also be defined as spirit or holiness or divinity. Rooted in the tactile and quotidian, they leap from their contemplation of birds, trees, and tract houses to the deep interior world of the speaker which, at the same time, reaches through and beyond to an enormous otherness.

“Go On,” the book’s first poem, exemplifies this seamless shift between outer and inner worlds, and of the largeness Rackin is able to communicate within such a small space. Composed of a single stanza of sixteen lines — one long, unpunctuated sentence — “Go On” addresses a “you” (some aspect of the speaker? the reader? an unknown other? — I don’t know, and love it that I don’t) who is at first seeking a “musician” who “is in no way more real / than you are now.” The musician feels like a romantic figure (“carrying a sheet of notes / under the cypress tree”), a natural object of yearning. But the “you” is just as real, just as important, as the dreamlike and sought-after, and Rackin’s speaker addresses her tenderly: “stay in the park a little longer reading / go down to the water if you like” (5). Whether or not the musician can be found, the “you” of this poem matters: her desires, the dailiness of her actions, her searching; she is worthy of consideration and care. In poem after poem in Go On, the everyday matters, as does the numinous, and Rackin’s swiftness in shifting from one to the other seems to indicate there’s not really much — if any — distance between them.

Todd: That shift does seem swift in terms of the poetic line being a measure of time, sound, rhythm, inflection. Yet if “a poem is palpable and mute,”[2] as MacLeish proposes, these shifts feel beyond time, as if the poems themselves are occurring in a thin place, a location where the wall between matter and spirit is porous enough to pass through, as with a permeable membrane or a meditation. In addition to time collapsing, in some poems the distancing of meaning collapses, falls apart. Instead of identification, word becomes association, casting its seine net through etymology, allusion, implication, and homophonic association, reminding (the reader) that it’s too mean to mean. In “Streaming,” a poem that signals a shift toward the quiet close of Go On, the language of the spare opening lines slips into possibility and mystery, rather than denotation: from “Too much time / on the line / and too much pining” (50) an image arises of hours spent (or wasted?) online or on the phone line, the factory line, the long gray/blue/olive drab line of military regiments, the clothes line. The language holds itself open to overstimulation, accountability, and clothes drying in fresh air.

The music of the first six lines of “Streaming” seems to cue reading them aloud:

Too much time

on the line

and too much pining—

screens shine bright

the same bare longing

lingering— (50)

The opening pair of lines is not an underarticulated image-phrase but rather an aural assemblage whose sound leads to a range of associations. It’s the poem’s tonal trigger, both as sound and as sensibility. The line that follows, however, immediately plays with and delimits these initial associations with the appearance of the word “pining,” a visual and homophonic pun that simultaneously puts forward the image of laundry pinned to the line and overlays it, in the fifth line, with a sense of mourning or desire. That high cry of the long “i” in “line” is a corrective that turns “pinning” (the laundry to the line) into “pining,” and turns the experience of duration or of the measured time of “too long” into the emotional experience of “bare longing,” the suffering that suffuses human life. The cry that sounds is the lament of the “I” too long on the line of insisting on itself. Its pitch marks the assonantal path the poem takes through longing to a glimpse of the damage it inflicts, the blight of seeing that, if clouded by want, seeks a silver lining. The ultimate line is a reminder that clouds may be “no brighter than their linings” (50). Because the poem courses forward on sound, its sensibility is submerged in syntactic link-ups and phonemic blurs that are mysterious or befuddling, veering from what they seem to signify. Is the “pine” of line 10 a tree or is it a repetition of longing? As St. John of the Cross writes in “Ascent of Mt. Carmel 1.13.11,” “To come to the knowledge you have not, you must go in a way in which you know not.” There is no map for this journey, but the poem creates a song line for it.

Jueds: J. C., it’s such a rich and layered reading of that poem. I love your invocation and definition of the “thin place.” And I agree the poems live there, in a space both beyond time and beyond distinction between spirit and matter. They really live beyond all sorts of distinctions we habitually make: between dream and reality, self and other, outer and inner.

What you wrote about the work being “mysterious” and “befuddling,” and the gorgeous quotation from John of the Cross, both remind me of how often the question of “understanding” arose for me as I read Go On. The poems certainly progress in a way I “know not,” have no familiarity with nor map for — and yet I feel a profound trust for the poems themselves and for their speaker. Perhaps that’s due in part to the tender address of the title poem, a poem that does feel addressed to me, the reader, to the part of me that yearns and longs. I think you’re right that the poems understand the damage longing inflicts — and yet they also accept longing as part of the human condition. Again, I feel Rackin’s Buddhist sensibility keenly here: her awareness of desire and suffering, and her compassion for those profoundly human states.

I think my trust in the poems also springs from their rootedness in the physical and quotidian — so essential in poetry it seems like a cliché to mention it. But the physical world feels extra essential in Go On, with its startling shifts, its associative leaps, its — as you point out — words that may, or may not, signify what they seem to signify. Here is the whole of a poem I love, “In an Ancient Forest”:

Betwixt a grove of trees—

flowers, fir, and ferns—

in the drunken forest I

have seen it—

with mine own eyes—

true for a girl on this side. (11)

Where to begin? There’s so much in these six lines. The long “o” and “e” of “grove” and “trees” shifting to a litany of long “i”s: I, mine, eyes, side. The forest is both profoundly real to me (flowers, fir, and ferns: I know these things) and profoundly other, a place of magic or divinity. The strange archaic turn of “betwixt” and “mine” coupled with the plain-spokenness of “I / have seen it.” The undefined “it,” which reminds me of the way in certain languages (Hebrew is an example) the word for God can’t be written, because God is a concept beyond writing, beyond speech. There are no rules here: the poem goes in a way I know not. But the poem itself knows the way it is going. There is no doubt (I don’t feel any) that the speaker has seen “it,” that the “girl on this side” has access to what feels like an entirely other side.

Todd: I also trusted “In an Ancient Forest” to be truly said, Kasey, and now you have me wondering why. Despite the archaic words, the poem sounds spoken into this moment. Although I’m reading it, my experience is that I’m hearing it. “Betwixt” slows me down so I pay attention to the voice in my head, which is “my” voice assembling the scene as what is. It seems that I’m speaking, true to this moment of seeing across and into another world. What’s more, that which is spoken is unable to be erased. Unlike writing, in which revision is both deletion and addition, in speech, addition — saying more — is the only way to revise. This short poem says what it needs to say and no more. It’s one of many that has settled into its moment. The frank economy of poem after poem coheres into a path and a tone, a kind of walking meditation that opens into questions. Here’s one: are some of the poems rescripts of others? For instance, is the final poem, “There Are Flowers” an end-of-the-journey rescripting of the first poem, “Go On”? One of the palpable wonders of Rackin’s poems is that they send me wandering off to others. They do not bind me to the path the poet has laid down, but stepping off trail, I follow connections sparked by language, music, image, and faintly surfacing memories, searching out associations that perhaps the poems do not intend, staying “in the park a little longer reading, / go[ing] down to the water if [I] like” (5). It’s a rare pleasure to stay in a book because its discoveries continue to unfold — “every step an arrival,”[3] as Denise Levertov writes in the title poem to Overland to the Islands. With this association, I’m rescripting all I’ve written here into its most economical form.

Jueds: Your naming of the poems and the book as a whole as a sort of walking meditation feels perfect to me, and reminds me of Roethke: “I learn by going where I have to go.” The poems do make a path — though one, as you said, that doesn’t always lead in a straight line, but curves, meanders, encourages the reader to loop back or step off the trail and ponder. I’m thinking of another favorite poem from the book now, “Night Boats,” which comes from the beginning of the collection and praises the “night-drifting” boats which are “definitely approaching something.” The poem continues: “how then can I be distressed / for they have taken on the work / my life has demanded” (6). There’s a path here, too, a journey, though the boats “drift,” not following a set course. And in not doing so, somehow, they exude compassion for the speaker and her life.

In response to your question about whether some of the later poems in the book are revisitings of others, I want to say: yes! “The Route” seems to speak to “Night Boats,” countering the drifting, mysterious, and magical boats moving toward “something” with seemingly simple declarative statements: “the trees there were trees,” the speaker in “The Route” says, “the question as to whether they were real trees / whether they were standing in for something else / whether you could mill their sap or what / honestly honestly never came up” (48). This time it’s the speaker, not a “stand in” like the boats, who’s on a journey, a route “down by the river.” The poem feels forthright and self-contained. And at the same time (again, I’m amazed by how enormous Rackin’s poems are within their smallness), the river here takes me back to the water in “Go On” and the ocean of “Night Boats,” both of which are real and otherworldly, literal and beyond literal. Along with rescripting, I want to say the poems are in continuous dialogue with each other, speaking back and forth, sharing their different and overlapping bodies of knowledge.

And I agree with you that the book’s final poem feels like a response to “Go On,” the yearning in that first poem answered so beautifully with the definite, yet still mysterious, two-line “There Are Flowers”:

And there is a well

beyond these mills. (56)

It’s as if the questions and longing in “Go On” — a relatively long poem — have found a place to rest here, in one of the briefest poems in the book and its single, declarative sentence. And at the same time that “There Are Flowers” offers a sort of blessing and promise, a place to stop, it also offers a way to continue. The path goes on, with the well that is “beyond” the mills and beyond the poem’s, and the book’s, end.

1. Ethel Rackin, Go On (Anderson, SC: Parlor Press, 2016), 5.

2. Archibald MacLeish, Collected Poems, 1917–1982 (New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin, 1985), 106.

3. Denise Levertov, The Collected Poems of Denise Levertov, ed. Paul A. Lacey (New York, NY: New Directions, 2013), 65.