Ecologies of the margin

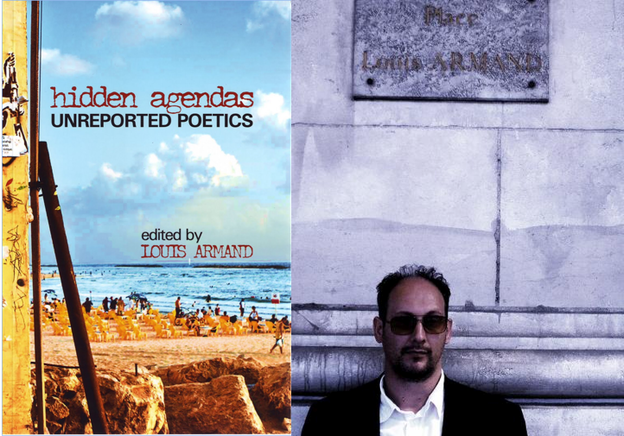

A review of 'Hidden Agendas: Unreported Poetics'

Hidden Agendas: Unreported Poetics

Hidden Agendas: Unreported Poetics

Hidden Agendas: Unreported Poetics, edited by Louis Armand, collects essays by poets about marginal poetries and poets; recalling John Ashbery’s series of lectures on unknown poets, Other Traditions. Hidden Agendas does not purport to be some kind of conclusive collection of marginal poetics; its premise, rather, is refreshingly contingent on personal proclivity: “a number of writers / editors were invited to reflect on a poet, a group of poets, or a poetics from the last half-century, that they deemed of personal significance and which they felt to have been underestimated, neglected, or overlooked. Consequently, each contribution is subjective and critical” (4).

Indeed most of the book’s eighteen contributors are probably better known than their subjects. Roughly half of these contributions are about poets and their work; the other half about (the concept of a) poetics. The essays about poets include: Kyle Schlesinger about Asa Benveniste, Robert Sheppard about Bob Cobbing, John Wilkinson about Mark Hyatt, Vincent Katz about Edwin Denby’s sonnet series “Mediterranean Cities,” Stephan Delbos about William Bronk, Jeremy Davies about Gilbert Sorrentino, Louis Armand about Lukasz Tomin, and Michael Rothenberg about Phillip Walen. The essays about poetics include: Stephanie Strickland about digital poetry, D. J. Huppatz with a history of Flarf, and Allen Fisher with an essay about complexity and incoherence.

Before looking at these and other essays, let us first return briefly to the book’s title, Hidden Agendas: Unreported Poetics, which immediately lays bare the apparent paradox of this anthology: are we offered a report of the unreported, an exposition of the hidden, a centralizing of the marginal? Not necessarily. Perhaps these poets and poetries will be allowed to remain hidden, unreported and marginal even as they are examined in this book. This is true in the obvious sense that this one anthology is unlikely to lead to a widespread retroactive appropriation of these various poets into the various canons from which they have hitherto indeed remained hidden in the unreported shadows of their margins. However, as Louis Armand writes in “Notes in lieu of an Introduction”: “an unreported poetics could not be allowed to simply be thought of as the disenfranchised other of a presumed mainstream” (3).

Another possibility, then, is to consider the marginal not in resentful opposition to the canonical, but as an expression of its own kind of affective difference. “[T]here is the question of how ‘marginality’ itself may be seen to underwrite a poetics — not simply a style or poetic stance, but a technics of composition” (2). Looking, for example, at one etymological root of the word “margin,” we find that apart from meaning something of little consequence, something that resides on the edge of the center, it also shares a root with “mark,” namely, “mereg-” (edge, boundary). For the word “mark” this has a recorded meaning of “sign of a boundary” → “any visible trace or impression.”[1] So a remnant of this slight trace or impression can also be thought of as lingering as an effect of the margin, allowing us to think of it affirmatively instead of appositionally. Instead of dismissing the margin as the boundary between text and the edge of the page, perhaps we can think of it in terms of what traces it leaves at this boundary of text and space. Much like Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of minor literature, Pierre Joris’s (Deleuze-inspired) Nomad Poetics, or Joan Retallack’s poethics of the swerve, a literature that is marginalized in this sense is not one that is forced into a position of powerlessness but one that merely makes a slight difference, leaves a nearly imperceptible, but not insignificant, trace. As a way into this book, Hidden Agendas, we can thus ask: What singular impressions do these poets and poetics leave? What is it that makes them marginal?

Of course the marginal subsists in what is major, mainstream, of “central importance”; in the same way that mainstream literature/art will carry traces of the inassimilable, the outside, the margin. “The marginal is a complex — a whole web of parallel universes surrounding and overlapping whatever purports to constitute a ‘centre’, yet about which it remains in the dark” (5). What does this notion of the margin as a complex mean? Alternatively to thinking about the margin as something that has veered away from a “the centre,” [2] the margin as a complex might be thought of as being part of the interconnectedness of things — what Timothy Morton has theorized as the Mesh — in which of course there is “a centre” depending on where you stand.[3] But thinking in terms of a complex, or mesh, allows one to think from below about how a poem emerges from its particular circumstances, instead of imposing from above a normative standard in which it must somehow be straightjacketed.

A marginal poetics — alternatively to being opposed to the mainstream — can thus be a poetics of the mesh, an ecology of poetry. British artist, poet, and critic Allen Fisher takes a similar approach in his closing contribution to Hidden Agendas, proposing a diagrammatic poetics, which tries to include a diagram of the poet’s whole environment in the poetic process. Instead of the poem emerging from the supposed deep recesses of a poet’s sensitive mind observing the world from a distance, Fisher prefers to talk about the poetic process in terms of a poet’s proprioception (the body’s sense of itself and its spatial surroundings) in relation to its environment. The focus is not on an ostensibly coherent collection of words that appear as if out of nowhere on a blank page, but precisely on the surroundings that give rise to a poem, what Fisher calls, somewhat awkwardly perhaps, archaeological spacetime. When the poem starts from the poet’s proprioception, “it comprehends the planet as home and proposes both a dig down and a dig upwards, by which can be meant an understanding made cogent from both historical perspective and geological information … the archeological spacetime implicitly fields an ecological understanding in all directions …” (249). An explicit reference here is Charles Olson (d. 1970) who similarly emphasized the specificity of place as a constantly reiterative creation of a Polis, a coexisting.

Similarly to Olson, too, Fisher extends his discussion of the ecology of poetics to include superficially unrelated disciplines such as archaeology, mythology, modernism, theoretical biology, quantum mechanics, and contemporary literary theory. Ecology, the diagrammatic, spacetime; all concepts that emphasize spatiality and dimensionality (as opposed to viewing a poem as no more than the flat words on the page). Letting in spatiality and ecology means recognizing not only a coherence in any situation, but also the inhering incoherence. So in addition to the poem as a straightforward linear narrative, Fisher examines the possible ramifications for poetry of different facets of incoherence and chaos.

Fisher’s multifocal style zaps through historical eras, scientific disciplines, and schools of thought, sometimes within the same paragraph. Witness his discussion of incoherence in which Fisher begins with a rejection of Plato’s view of poetry (as intuited “mental poison” and “enemy of truth”), then jumps forward twenty-five hundred years to cite Alan Turing’s insolvability solution (which proved that there are mathematical problems which cannot be solved by pure logic, thus demonstrating, “within mathematics itself, […] the inadequacy of ‘reason’”), only to borrow from theoretical biology the concept of chreod — which refers to the necessary paths for brain activity and cognition — as an example of the inherence of chaos in equilibrium and vice versa; subsequently showing how this can be “ventriloquized” in poetry in as much as poets’ “consistent patterns or chreods in the cellular connections of their speech productions are characterized and can be discerned in the patterns of their language presentations”[2] (253, 257, 259).

In part two of the essay Fisher discusses Joan Retallack’s Poethics as an example of a poetics of incoherence. Retallack’s poethics of the swerve too stresses nonlinearity and complexity and chaos theory as inspirations for her poethics. “How can one frame a poetics of the swerve, a constructive preoccupation with what are unpredictable forms of change?’ (271). Her swerve brings to mind many other such references to a minor or marginal movement that nevertheless is an impetus for/of change: Lucretius’s famous clinamen (the unpredictable swerve of atoms), or Deleuze/Guattari’s nomadic becoming minor (a movement always away from the major). Retallack writes: “Imagining a cultural coastline (complex, dynamic) rather than time’s horizon … thrusts the thought experiment into the distinctly contemporary moment of a fractal poetics” (274).

So where along this complex and fractured coastline do some of these forgotten poets surface? What swerves did they make in their environments and in their poetry’s environments that make them memorably marginal? And how do we find them if not in the neat chronological presentation of the school textbook, the bookstore’s alphabetically ordered poetry section, the ostensibly all-inclusive, decisive anthology? Hidden Agendas offers a variety of answers to these questions. Amongst these, one very intriguing sounding poet is Lukasz Tomin, whose short life and virtuosic writing is introduced by Louis Armand.

Lukasz Tomin’s life and work started from various positions of marginality. It is poignantly ironic that, born in 1966, he grew up during normalizace, the period from about 1969–1987 that saw the reestablishing of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, in reaction to the reforms of the Prague Spring. As the son of dissident intellectuals, Tomin moved around during his childhood, first to London, then France. Later he moved back to Prague, but by now he had made the choice to write in English, a third degree of marginalization, and one that, at first, alienated him from both the Czech and UK literary circles.

So does Tomin’s personal entanglement within the political turmoil of his time find direct expression in his writing? Is his writing positioned in opposition to the “normalizing” tendencies of the Czech state to which he returned? The answer appears to be both yes and no: Armand argues that Tomin’s writing is not overtly political, but that it is precisely in this rejection to engage with the political agenda as set by the state that Tomin creates works that think directly about “the secret life of what we call ethics” (118): “In the context of the post-Revolution literary nationalism, Tomin’s writing carries no instructive message — it remains alien, unassimilated and ostensibly inassimilable. Against the poetics of tribal evocation, Tomin’s is a poetics of dispossession” (123).

The Doll, for example (the first of three books that Tomin wrote), is on one level a story of the escape and travels of two children who plan to build a large doll as a symbol of hope, but with a Bataillean flavor and “steeped in the ‘perversity of innocence’” the children’s plan “gives way to self-flagellation, confusion, and dissipation” (118). Armand suggests that not only can this be seen as an allegory of itself, it can furthermore be thought of precisely as a critique of allegory, as a tired and ineffectual, and overly didactic form (popular we mustn’t forget, amongst exiled writers, artists, composers) that no longer sufficed as a vehicle for social change. It is not surprising therefore that Tomin, too, rejected a linear coherent style, but rather wrote layered texts which were “a surface kinetics of interpenetrating ‘figures,’” in which “one thing does not lead to another; everything is rather détourned.” (120, 122)

Despite the meaningful and lasting effort Armand argues that Tomin contributed through literature to that “secret life of what we call ethics,” Tomin did not live to see recognition for his writing: he committed suicide at the age of thirty-two (118). And although he is discussed as someone who was not interested in confessional poetry of sentiment, the fragment with which Armand closes his essay hints of the personal darkness with which this young writer must have been struggling:

With an ending.

Try to be homeward try to be sane.

In the river.

Of your choosing.

Secure the wranglings of madmen.

To a nowhere.

Another singular example in Hidden Agendas of a poet writing from the margins is the English poet Mark Hyatt (1940–1973). A drug abuser, gay, and semiliterate, the margins Hyatt was writing from were those of adaptation to the norms of society and “proper” standard English. An important point that Wilkinson makes in his essay is that if subjected to formalist, normative (or, if you will, normalizing) close-reading, Hyatt might not be said to have written many good poems; and yet, Wilkinson argues that Hyatt’s poetry holds up to extended and repeated readings. In a way, Wilkinson writes, Hyatt’s work can be qualified as, “stoner poetry; amidst a general vagueness more or less interestingly warped from poem to poem, something amazing occurs and amazingly often.” (52). Here are some of those lines:

and I am having one

of those sexless nights

where birds fly out

of the mouth

with their tails

on fire. (62)

And from another poem: “He steals a small poem / And scars it madly” (53). Lines that are — remembering Hyatt’s semi-literacy — pertinent, and even more so when we learn that he even often did not want his grammatical mistakes to be corrected.

Hidden Agendas as a whole is certainly a motley collection, both in the variety of obscure and unknown poets and in the different approaches taken to introduce them to the reader. Although this variegated approach mostly works, some contributions unavoidably seem to be less synchronized with the rest of the anthology. Huppatz’s essay on Flarf, for one, in its very structured and chronological presentation of the movement, feels strangely canonizing for a book about marginalism. Johanna Drucker’s playful essay offers a more titillating counterpoint to Huppatz’s effort. Drucker presents an episode in the history of Language Poetry in the form of a kind of fantasy novel:

The leaders of the LangPo were scattered, one of whom had chief influence in New York, exceedingly beloved by many people, and others among the Canadians, and the Californians, but their forces were still gathering out of sight to put down the Workshop poets and convert the Traditionalists. (189)

Michael Rothenberg’s contribution about Philip Whalen might for some also be somewhat awkward. Rothenberg’s piece consists of fragments of highly personal conversation and poems from what appears to be Whalen’s last few weeks in hospital, sometimes giving the reader an uncomfortable sensation of voyeurism and nostalgic sentimentalism. A different issue is whether Whalen can really be said to be unfairly forgotten — as recent as 2007 there appeared the nearly one thousand-page tome The Collected Poems of Philip Whalen with forewords and introductions by the likes of Gary Snyder and Leslie Scalapino.

Nevertheless, Hidden Agendas is a welcome stringing together of diverse and forgotten poetic fringes into one diverse collection. It is devoid of the snide competitive remarks sometimes found in academic writing, perhaps since the emphasis in these essays is on personal tribute to a particular poet or poetics. Also, the fact that there is no real organising principle to the book apart from its eclecticism really complements its starting point of poetry as emerging from a complex of factors. It is definitely exciting to have the feeling of sifting through fragments of the past and learning about nearly forgotten poets. The thorough documentation, research (including some nice chapbook cover artwork), and close-readings in many of the essays certainly add to this experience. Hidden Agendas is another of many innovative volumes brought out by the prolific Prague based publisher Litteraria Pragensia.

1. From The Online Etymology Dictionary.

2. This eclectic style can be absorbing and is even sometimes deployed more explicitly as a rhetorical tool to underscore his defence of incoherence. For example, there is a passage of disjunctively written sentences; as well as one grammatically incorrect sentence that is purposively left as it was first typed. Ironically, however, at other times Fisher’s style can be unnecessarily dense, and in these cases unintentionally borders on the incoherent.

3. Timothy Morton, Ecology Without Nature (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2007).