'To drown well is art'

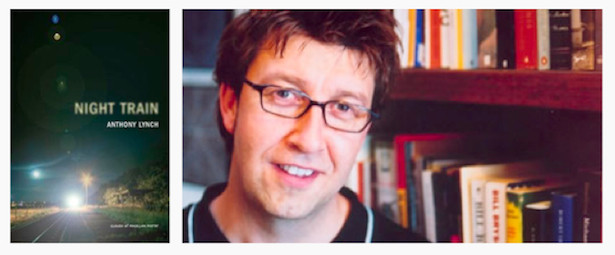

A review of Anthony Lynch's 'Night Train'

Night Train

Night Train

Night Train is Anthony Lynch’s first book of poetry, and it comes with a small list of weighty names in its acknowledgements. This promises to be poetry that has been carefully hefted, sifted, culled, and considered. In addition, Anthony Lynch is not only a fine short story writer, but is himself a professional editor and a publisher of poetry. To know what you are doing can be a dangerous starting point for a poet and for poetry, so it is with relief that I found the last line of the first poem suggesting “To drown well is art.”

This first poem has the openness of free verse, the kind of short-lined free verse where missteps are quickly exposed. It has the formality of three-line stanzas and a faintly self-mocking tone as it takes us through references to a Mandelbrot set, a climatologist’s beard, the after-rain songs of birds, and a brief theory of puddles via a dog (summed up in the phrase above). The lines are beautifully paced down the page, sometimes in a phrase so expertly handled you have to stop (“on a nub of hill”) and the whole carries a voice that’s interesting already. The first section, “Topography,” introduces the reader to landscape, weather, animals, and a faux-scientific vision that either accepts drowning “well” or aspires to that condition. This poetry can walk us vigorously across a farming landscape, alert us to the slaughter that is part of farming as well as those compromised versions of nature that go to constitute farming country (foxes, rats, genetically modified canola, hares, invading bees). The poet is there with us, simply, and we trust him, while the poetry continues in its steady short lines that pace themselves with steps that don’t stretch the breath but feel alive mostly because of the liveliness of the mind that subjects itself to the compact diction of the poetry: a sheep unplugged by a fox; a mop squeezed out in the sky; an octopus of hose; dumbstruck shirts on the clothesline; a pelican that “jumbos over the bay”; and in a train, “upon reflection, the dark windows clone you.” These images I have almost randomly chosen, for the arresting moments are so frequent that it takes more than one reading to catch them all.

In the second section of the book, more concretely titled “Interiors,” there is a closer world of sex, love, domesticity, personal rivalries, and depression, with shifting moods in the phrases that are so condensed, again, you have to stop to savor them:

The past exits the back door

where pot plants do their time.

(“The Vexing”)

Lynch does what the best poets do: he inhabits whatever he describes. You feel he has learned something important for himself from Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath without ignoring William Carlos Williams. Brendan Ryan’s and Laurie Duggan’s regional poetry forms a sympathetic spirit close to this poetry too.

The final section, “Splitting Space,” develops notes of urgency alongside a more open humor. The violence of the duck season, addressed jokingly to the ducks (“come be my quilt / or quill”) is expressed with what seems carelessness of tone after the early poems. It is as if almost any image will do as long as it breaks away from expectations, even from poetry, for the questions about violence must take precedence even over the poetry. A caustic vision takes over: Christmas is summed up with “the bonbons a reliable bad joke.” His black humor becomes reliable as he observes mercilessly the demented and the crippled. Nine people die on the final night train in the book. The subliminal expression of violence in this poet’s surname comes to my mind at the end. It is as if he is giving himself up to himself, though Saint Anthony, the orator who knew with devilish skill how language works, is there too. If this third section is more recent poetry, then the reckless urgency coursing through it is a good sign for the next book from this poet.

Mostly this is a poetry of observation rather than sentiment. The “inhabiting” always carries with it ideas and attitudes that won’t let you, or the things observed, alone:

All too strange

or too familiar, we can’t decide

(“Blooming”)

Sean O’Brien, the British poet and novelist, speaks of the unreasonable reason that must be present in the best poetry. It is there in Anthony Lynch’s. It is this stance of the thinker-observer that makes the themes of forgiveness, violence, of “want and consent” shine through when they’re glimpsed. You realize they have been all over the poetry from the beginning while the brilliant visuals have kept you entertained. The violence is not, of course, simply there because it happens to be part of the panorama, a daily thing. That would be one attitude to take. Lynch notes the violence of the mundane has been called the stark reality of day, in order for his poetry to show that phrase up for the stale cliché it is. It is the “bigness of things” he shows us, and mostly through his small, brilliant details. His poetry drowns well in its final image of a library of all possible faces.