Dorothea Lasky, it’s unbelievable

A review of 'Black Life' and 'Awe'

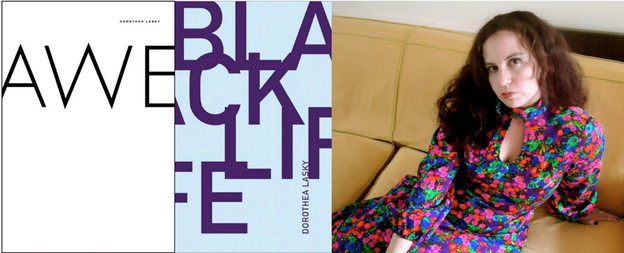

AWE

AWE

Black Life

Black Life

I couldn’t sleep tonight so I started a new diary. On the first page I wrote the following quotation about Iceland, by Eileen Myles:

Most likely we travel to exist in an analogue to our life’s dilemmas. It’s like a spaceship. The work for the traveler is making the effort to understand that the place you are moving through is real and the solution to your increasingly absent problems is forgetting. To see them in a burst as you are vanishing into the world. Travel is not transcendence. It’s immanence. It’s trying to be here.

I love how Eileen always compares poets to astronauts. In August I moved to Buffalo, New York, where for five months of the year the sky turns an opaque, sour-milky gray. Dear diary, I’ve been trying hard to be here.

In one poem Dorothea Lasky imagines herself “soaring in the black night as just a thing,” and somewhere else calls herself “star-filled.” Both lines appear in her recent manuscript Black Life (in which “star” and various forms of “sad” are probably the two most used words), but her writing has cast the radiance of real human presence against the immense loneliness of deep space for a long time. Like a Jeff Mangum song, her second chapbook Art for instance imagined “the tiny babies of the universe” who would “explode” from out of her womb. My friend Myung Mi Kim has written that “the practice of the poem is the practice of a radical materiality.” I completely identify with that. But because Lasky’s work carries forward an underrecognized, immanentist literary materialism of extreme presence, negative affect, and wild lyric impersonation (rather than a more myopic “materiality of the signifier”), I’m always disappointed with the way people talk about it.

One week this bitter winter I spent almost thirty hours transcribing an interview between Chris Kraus and Penny Arcade, recorded last June. It’s weird how transcription can blur into you, focus your attention on someone else’s voice so closely you absorb and internalize it. I wandered lost around an empty antique mall in Western New York sometime after New Year’s, thinking like Penny. In one place on the tape, she says this:

But I want to say, for younger artists … you know, because one of the things is that … you know, this has gone on for 20 years … people see me perform, they work with me, and I talk directly to the audience. Which was one of the things that I created, which now has like, you know, an actual academic name, which is “direct address,” right? And I started speaking directly to the audience because I was so ignored by the press and the art scene. And so I would talk directly to the audience. I understood that my relationship was with the audience. And so I developed that, and just got braver and braver and braver … because I’m a very frightened person emotionally … And so at any rate … a lot of younger people who’d work with me, they’d see me talk directly to the audience, and they’d go, “oh, I can do that,” you know? And they didn’t understand the level of integrity that you have to bring to talking directly to the audience. Because … it doesn’t work unless you’re really at risk.

I copied Penny’s quote into my diary too. As a literary form, the diary is a kind of modality of direct address, except it’s not very risky because we usually hide them. Lyric poems can approach direct address, too, but the apostrophe itself usually proceeds from a secure and formal absence of audience.

Because her poems so dramatically reinhabit emotion, one of the most perfect lines Lasky’s ever written (from AWE) is “Conceptual art, you are dead / Language poetry, you know how I feel.” In a slow-learning poetry culture where the cool vacancy of writing based on these aesthetic currents of the 70s and 80s is still considered avant-garde, I think it’s taken an unbelievable amount of integrity for Lasky to make unironic and very public announcements like this one, or to say “I hate irony // I am only being real.” Although I’m friends with people who’ve misread her affective and unembarrassed realism as a kind of nostalgia, or “naive” (if put-on) reaction to things like Language writing and its attendant “critique of authenticity,” Lasky’s lines like these read so flatly because she’s not being defensive: her poems aren’t troubled by such poetics, but simply identify with an entirely different, more minor poetry/performance-art tradition (and one that’s never cared to promote itself with its own technical vocabulary). While she is thus endlessly confused by reviewers surprised at her “earnest sincerity” with the allegedly self-absorbed “confessional” poets of midcentury, for me Lasky has most in common with a stylistically diverse line of usually forgotten and mostly soulsick writers who’ve inhabited language literally, and risked using the poem as a kind of depersonalizing, radically signifying material. Reading Tourmaline and Black Life this morning, I think immediately of Arcade, Kraus, and Myles, Catullus, John Wieners, Ariana Reines, Tao Lin, Tracey Emin.

Here is an entire poem from Black Life:

JAKOB

I am sick of feeling

I never eat or sleep

I just sit here and let the words burn into me

I know you love her

And don’t love me

No, I don’t think you love her

I know there are clouds that are very pretty

I know there are clouds that trundle round the globe

I take anything I can to get to love

Live things are what the world is made of

Live things are black

Black in that they forgot where they came from

I have not forgotten, however I choose not to feel

Those places that have burned into me

There is too much burning here, I’m afraid

Readers, you read flat words

Inside here are many moments

In which I have screamed in pain

As the flames ate me

Opposite the confessional, one signal ethic of Lasky’s writing is a spectacular disabling of lyric personality. What I mean by “depersonalizing” above is written here in the emotionally flat, anaphorically insistent way that Dorothea has lined up so many deadpan I’s along the left side of her poem. She begins declaratively sick of feeling, and then lets her own abject and disaffected persona unravel and self-immolate in line after line of negative emotion, until her sick-day poem finally burns bodily into and through herself. In other words, Lasky disables the affective singularity of first-person lyric enunciation by overinhabiting the form to a kind of self-destructive, nearly ontologic limit-point. As the poet is visibly consumed in flames, her body becomes a wild object, and her emotions a kind of impersonal energy passing through her. It’s an incredible twist Lasky is constantly pulling off, surely learned from her idol Sylvia Plath (who in a poem titled “Fever 103°” once wrote, “Darling, all night / I have been flickering off, on, off, on”). “Like love,” Lasky writes, “I so did contain many voices that weren’t mine.”

My favorite two poems of Dorothea’s are titled “I Just Feel So Bad” and “I Hate You.” “I Hate You” begins:

I have thought and thought about it

And I hate you

And what I hate about you most is that

You have no real understanding of the sublime

I hope the white light crushes in on you

And crushes everything about you

Although I suspect some people might read Black Life as a depressed departure from the perceived levity of AWE (which one reviewer characterized as “kind of like … getting chapped lips at a slumber party, after an intense round of Cyndi Lauper lip-synching/dance performance moves”), even Lasky’s more plainly wonderstruck poems have always been directly involved with the problem of writing presentationally about blocked and unglamorous emotions. In an interview shortly after AWE’s publication, Lasky tried to explain this dark underside to the book’s more clearly life-affirmative poems like “Poem for My Best Friend”: “I totally meant for the idea of awe to invoke a complex and terrible emotion,” she said.

In her recent volume Ugly Feelings, literary critic Sianne Ngai notes that the Kantian sublime (with which memorable sections of AWE as well as Lasky’s later and uncollected hatred series seem fascinated) is “perhaps the first ‘ugly’ or explicitly nonbeautiful feeling appearing in theories of aesthetic judgment.” Ngai also recites one of the philosopher’s own more lyric definitions of the affect: an “Astonishment that borders upon terror,” and a “dread” and a “holy awe” which terrifically “seize” the feeling person. Although Lasky’s hilariously deadpan and radically literal verse has absolutely nothing to do with the modified “stuplimity” that Ngai later suggests using to consider the recalcitrant texts of poets like Gertrude Stein, Samuel Beckett, and Bruce Andrews, I think Ugly Feelings still shares a tight, revisionary affinity with Lasky’s work for the way both exclaim the literary legitimacy of feeling badly. “All poetry that matters today has feelings in it,” Lasky writes in one place in Black Life; and in another, “Whatever you do don’t feel anything at all.”

Have you ever heard Dorothea read? She shouts the poems. It’s stunning. To remind myself that I was still alive on cold morning drives to TA freshman comp courses on a campus with very ugly architecture this winter, I listened to Ready to Die by the Notorious B.I.G. almost every single day. Usually, I would play the sixteenth track over and over. It’s un-be-liev-able / Biggie Smalls is the illest! It’s great because this posturing sendup of Biggie’s own fantastic lyrical prowess is the next to last song on the record, and then the last one is all about self-loathing and suicide. In another interview, Lasky once said, “I’m very concerned with how power occurs in a poem.” Besides Biggie, I’m unaware of any writer who has inhabited Charles Olson’s performative kinetics of “projective verse” to such an embodied extreme as she has. In high school Lasky competed the 3,200-meter long-distance run for her outdoor track team, and when she read in Buffalo last February she had to pause between verses of shouting AWE, AWE AND LOVE to ask a girl in the audience for a Gatorade. Maggie Nelson has recently written that Eileen Myles’s naked incorporation of private and metabolically charged lyric disclosures into scenes of live performance has worked to “transform the boundaries of what kinds of claims on public space a female poet can make.” When Lasky deadpans loud lines like Identity politics are bullshit, or I have to be protected / because I am so afraid, she further extends this same stage into what Thom Donovan has called a form of “biopolitical theater.” Within it, the poet’s startling voice creates an affective, material immediacy between herself and the audience that riskily opens the room up to an unprecedented sort of anti-identitarian, emotional access to her writing.

One sad thing about being in graduate school is that all your friends are basically adults, and successfully settled in normal, monogamous couples. Do you know the way that being surrounded by couples can make you feel excluded from all love? On nights this year when my married friends weren’t going out, I would usually stay in and read Dorothea or write her emails and dote on my cat, Winston. I discovered Lasky’s work about two years ago, after reading one of CAConrad’s inspired, inimitable rants on the UB Poetics List. A graduate student somewhere had blogged about Dorothea’s “infantile” and supposedly unfeminist answers to the Proust Questionnaire in a YouTube video (really), and Conrad fumed back that “Dorothea Lasky needs no one’s permission to act one way or the other. Those who actually read her poems understand exactly how and where she stands in the world. In 100 years when the rest of us are forgotten there will be Lasky.” The moment I read AWE I felt he was right, and when I opened the manuscript for Black Life this spring I smiled to see that one of the personas she’s invented to flicker through these days wears the tough-poet posture as well as Conrad does. One of the best poems in the book ends like this: “I give up / But it is a sweet giving up / Knowing instead I will be the best poet that has ever lived / While all those people in love / Will simply die in one another’s arms / While I will die in the world’s arms.”

Her poems are so good they make me gasp.

July 2009

Moon in Cancer

An earlier version of this review appeared in ON:Contemporary Practice 2.