Divine and now

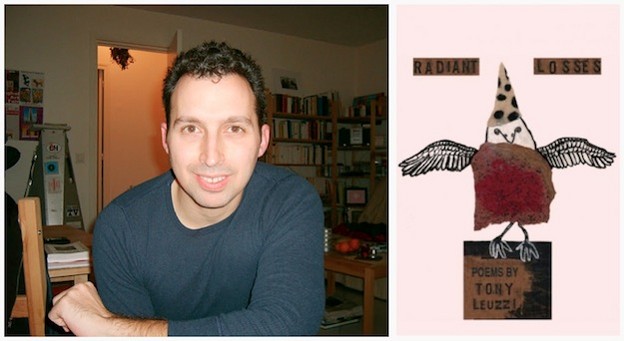

A review of Tony Leuzzi's 'Radiant Losses'

Radiant Losses

Radiant Losses

In his new collection Radiant Losses, Tony Leuzzi writes poems that are not only universal in topic and emotive power, but also very personal. Poems such as “Now” explore the physical and emotional connections between men: “The / less / he was / and the less / I was the more we / disappeared behind bodies not / our own …” In the last stanza of this poem, Leuzzi’s speaker reaches a metaphysical realization: “But / now / with you / I can’t think / of anyone else / hell! I can’t think at all! Your skin / against mine / my flesh, your flesh, the immediate this” (53). In these last lines, a unity has been achieved: sexuality is more than simply raw substance; it is divine and now.

Radiant Losses explores other erotic possibilities. In the poem “Today,” Leuzzi addresses the games played in seduction by telling the reader about the Cavalier poets and describing the rituals of attraction and seduction: “But they were men who pined for girls, / who teased the locks of chambers free.” Leuzzi sets up desire with a sense of urgency: “let’s do this now before we die” (16), suggesting the carpe diem theme of the Cavalier poets’ work. However, there is also irony in that statement: oftentimes what we so desperately want is spoken of and written about in tones that are lighthearted in order to hide our passion and desperation.

Two recurring themes in Leuzzi’s collection, longing and regret, are intertwined with each other and with the book’s title. It is not difficult to see how the title refers to loss that takes on the power of radiance through so much longing for an unrealized or lost love, event, or emotion. In “Joe Brainard,” Leuzzi’s speaker regrets that what is so obvious to him in retrospect was not so obvious to him at the time. He ends the poem with a luminous description of what he found through his regret: “I / re / member / this I re- / member that, and each / time the phrase appeared there was this / magic, pure and simple, a cold raindrop on my skin” (45). The poem reminds us of the way this longing for spiritual fulfillment helps us endure personal losses and regrets.

Leuzzi describes the interplay of emotion and intellect in “At Albright-Knox, 2003.” Through the purity of language and the unfolding of a vignette, the poem reveals how emotions and intellect are so closely aligned. The setting for this poem is a room that contains “nine abstract expressionist paintings.” To the uneducated eye, abstract expressionism is merely chaotic design. To critics and lovers of this style of painting, these works create both emotional and intellectual discovery. The speaker sees someone he desires, and the interplay is electric as the two figures look at each other, although briefly: “as if one’s undivided gaze / was a hand caressing the taut skins of canvases” (43).

Leuzzi leads us word by word and syllable by syllable into each poem; the poem’s vignette style further teases us with the simplicity of the idea, laying it all out very logically. However, by the last line of the poem, Leuzzi gives us the full emotional impact of the poem’s meaning. For example, in “Log Cabins,” Leuzzi moves the reader through a consideration of the gay Log Cabin members of the Republican Party. His last line contains the central image of the poem: “save a few huts collapsing in the wilderness” (41). Everything that Leuzzi had written up until that point points the reader to this conclusion; in some ways, it almost reads like a syllogism.

A poem with particularly powerful use of imagery is “On Ribera’s La Mujer Barbuda,” in which we see a series of images: “but a stout man with sturdy hands / and one enormous breast suspended from the center // of / his /chest like / a swollen / gourd soon to be plucked / and hollowed, then carefully strung / with gut for the lyre, on which a bard might weave weird tales” (49). The interpretation of visual art through language art tantalizes and gratifies that sensory need which many poets have to sustain themselves and to “weave weird tales.” It is an interesting and rewarding exercise to look at a piece of art or listen to music and rewrite the sensory images and feelings as a poem, and Leuzzi does this also using music as his muse in “Tchaikovsky’s ‘Impromptu.’” He uses the same tightly controlled style of other poems in which he slowly leads the reader into the situation of the poem, beginning, “In / F- / minor / begins with …” The first stanza ends, “swift as the pitter of kittens / across linoleum, patters like a little boy …” The poem builds in energy with more syllables that then move quickly to a conclusion. The music takes on the persona of a little boy, who changes his intent as it moves through the various movements, and surprises the reader with this ending: “surrenders arms to air and asks for cake” (47).

The language in this collection contains tightly controlled emotion hidden beneath more obvious meaning. Leuzzi uses compression to create emotional power that expresses itself as “radiant losses.” As a poet, I am also searching for the banal parts of life to be translated into those radiant moments and losses.