Devisable matter and sheer overjoy

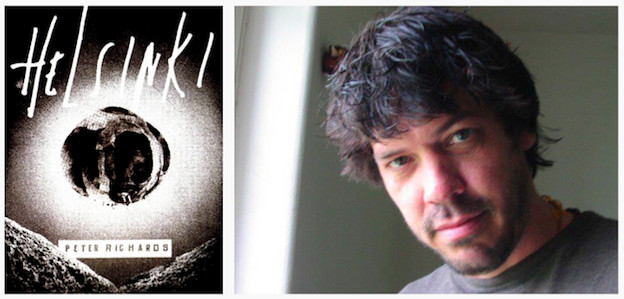

A review of Peter Richards's 'Helsinki'

Helsinki

Helsinki

Even though I might try to define Helsinki in Peter Richards’s latest collection of the same name, I don’t think it would be all that constructive an endeavor. It is, however, important to note that location is integral in that it is a reoccurring motif as well as the gesture of the book’s title. But when I say location, I hesitate to affirm the specificity that the wordimplies; rather, the locative forces that energize Helsinki do more to strip the idea of location of its specificity, transforming the lyric into a mode that sustains placelessness, a medium through which lush imagery and skewed perspective enact a state of being instead of a particular setting.

The poetry that populates Helsinki’s five sections does not have titles, only three addition symbols at the top of each page occupying the spaces where titles might go. Instead of the narrative suggested on the book’s back cover, we encounter the vestiges of narrative — phrases, words, and lines that haunt the space of the poems with their narrative signification, preying on the expectations of readers who want language to follow the same narrative patterns found elsewhere. This is no ordinary narrative; it is one that holds a funhouse mirror up to its own absence, distorting and distending where it would continue its usual causal relationships:

My own bad recollection landed me too much alive

to the first signs of disintegration in a prairie in a baby

metabolizing bees was the first sign my illness had presented

the feminine smell of devisable matter and sheer overjoy

The opening lines to the ninth poem of section one exemplify the narrative haunting of which I speak. The lines have no punctuation and allow for a kind of reading that shapeshifts and morphs. We encounter verbs that denote a feeling of narration (“landed,” “presented”), but this feeling is subverted by the way the lines hinge upon a precariousness that gives the poems a sense of wonder. “Was” sets up this precariousness; we seesaw between readings: “in a prairie in a baby / metabolizing bees” is a way of reading that forces the “was” to dangle indefinitely, whereas “metabolizing bees was the first sign” is another reading, but one that jars the line’s causal relationship to “the feminine smell of devisable matter.” And yet these readings coexist, rendering much of our desire for sense-making irrelevant.

Further on in the same poem, we read, “all the flash clubs / in Helsinki had the foresight to be in Helsinki everywhere,” which, on the surface, has all the familiarities that encourage us to read briskly (the lack of punctuation adds to this tempting briskness). But when this second line is read on its own — “in Helsinki had the foresight to be in Helsinki everywhere” — we are presented with issues of language’s visual trickery. The ‘i’ of Helsinki slips away from its word and forces us to reckon with a shadow line that occupies the same space: “in Helskini [I] had the foresight to be in Helsinki everywhere.” This moment captures placelessness in real kind of way — the “I” is everywhere and, thus, nowhere in the sense that it is also hidden in words that contain it.

Similarly, these poems contain beautiful lyric moments that seem to lift off the page just like the “I” separates from “Helsinki.” Take, for example this moment:

I think it must be cold so cold the cold outnumbers ice

From when the ice was young no tear has taken its place

So it must live beyond the great doors of winter and sing

As many flesh and blood songs as a frozen tear can sing

These beautiful lines arrive at the end of its poem, out of the memory-dreamscape of a “villa / my parents shared between them each room holding / a portrait of one of my parts.” While I would be inclined to suggest that these moments break the sustained tonality of Helsinki’s lyric mode, they operate with the same formal techniques as their surrounding lines creating a kind of netherworld where the lyric sustains its continuity as well as its breaks, giving everything equal resonance. Lines that precede or follow these lyric eruptions have the same feel to them, giving readers the odd sensation of being lifted out of the lyric space even when they are fully entrenched in it.

Considering this feeling of entrenchment, it comes as a surprise to encounter lines that provide a key to Helsinki’s many folds: “I am afraid my body will not convey so / let us melt as two rocks of pink flake.” The anxiety that one’s body and thus, one’s language, cannot adequately convey experience is not in-and-of-itself surprising, but when it is contained within a text so concerned with sensation and image-making, one cannot help but look to all the shape-shifting and morphing in Helsinki as a kind of struggle to make the lyric an immediate, transformative experience just as our experiences in the world have the capacity to bypass mediating forces (e.g. language) to transform us in a very real way. Regardless of the way the lyric struggles for immediacy in Helsinki, what we read cannot escape what muddles our world — our words and our desire to make sense of things — and so we have the rocks of pink flake, which still retain the same collection of molecules even when rearranged into melted form.

The impression that one cannot escape what creates us — for humans, sensory experience, for the poem, language, etc. — is manifested in various ways in Helsinki. The series of three plus signs that exist in place of titles as I previously mentioned are an example of this impression, linking the pages in anonymity, fusing them together into one poem, the poem, that which stands in for the lyric as well as the vague state-of-being evoked by allusions to specificity vis-à-vis Helsinki. Additionally, the occasional appearance of “yes” as a tick of affirmation — as in, “some light study yes but also on occasion they’d go out / dressed up as brash Catalan characters” — is another manifestation of this impression, revealing a related anxiety, an anxiety about the nature of truth and whether it might be possible to convey. Truth may not be able to be conveyed, so what we have in its place are the images and sensations that give our lives some semblance of shape, which is to say, “it feels really good / just letting the waves make their own history.”

It also feels really good letting the waves of Helsinki wash over you. That Peter Richards is able to sustain the book’s rampant curiosity for ninety-plus pages is a gargantuan feat. And though I might not be able to identify where Helsinki is in Helsinki or what it means with any exactitude, I revel in its placelessness and am no less awed.