Defiant lightness

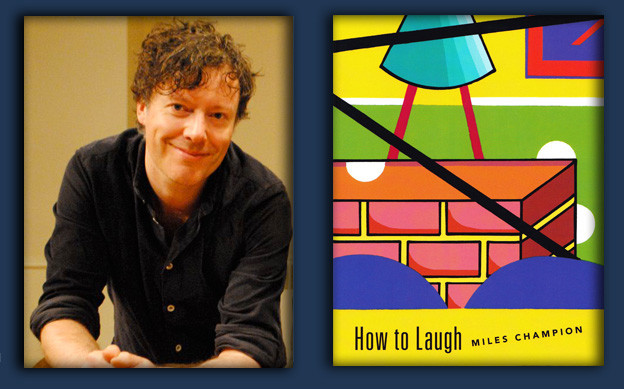

A review of Miles Champion's 'How to Laugh'

How to Laugh

How to Laugh

A wonderful moment occurs toward the close of How I Became a Painter, Miles Champion’s recently published book of conversations with the painter Trevor Winkfield, in which Winkfield switches roles on his erstwhile interviewer to ask candidly, “Why do you like my paintings?” For anyone reviewing Champion’s third poetry collection, How to Laugh, this excerpt from his response is hard to resist implementing as preface:

When I visited your studio I realized that we both work in similar ways: starting with one element and then casting around for another that might be interestingly added to it, not really knowing where things are going but trusting in — and enjoying — the process. And then, of course, once the painting is done, you have the sense to simply leave it midway between yourself and the viewer; there’s no conceptual armature or peripheral baggage to get in the way of or limit my enjoyment of it.[1]

What’s especially resonant in this lucid reply is Champion’s concern to “leave” the work “midway between yourself and the viewer.” The work — this decidedly classical ideal insists — is always facing the viewer, always accompanies the reader, just as Adrian Stokes envisioned ballet as a “turning out”: “Nothing is withdrawn, drawn inwards or hidden: everything is, artificially if you like, put outwards.”[2] The poems of How to Laugh are nothing if not “turned out”:

I walk by bouncing

up its pages

where clouds are

faint from farsight’s

tandem red brick

in spoke room

each clock face

to its interval[3]

“Turning out” demands not only that the architecture of a poem should eschew any enigmatic recesses in which feigned depth or posturing might lurk (so the theory goes), or a conceptual scaffolding that might disguise a lack of material integrity — but also, for Champion, that some convivial buoyancy should counter all that architectural weight. And so the title of this volume, with its mock pragmatism and disarming directness, comes into play: laughter as compositional tactic and stoic strategy. There are even out-loud laughs to be had:

In Sweden once this guy jiggled shrimps in yoghurt, contracted leprosy, and became a nun. His father had a silly name for welding struts to a can. (9)

he dictates correspondence in a housecoat

and special shoes with one-inch “verandas” (52)

The pact between lightness and architecture is sustained by a repertoire of keywords — “air,” “smoke,” “space,” “holes,” “fruit,” “dust” — that permeates this poetry, serving to delineate its physics and unifying How to Laugh as a collection possessed of both vitality (erotic, humorous, mobile) and a remove that’s best defined by what it shuns: the solemn, the morose, the overly cerebral, the pious, the didactic. Very occasionally, flashes of resolve emerge from this quietly defiant lightness, in lines such as “stop acting wet” (40) or “in that way a good result denies / The helping hand” (29).

It’s useful to pause and recall the predominant poetry culture in which some of these poems (and Champion’s two previous collections) were written — the ostensible leftfield of British poetry in the 1990s and early 2000s, where the repurposing of wounded libido as political disgust was (as it remains) a widely endorsed method for building poems. Such a mode, whereby the poem’s propulsion is essentially a given from the start — “replacing flexible attention with inflexible intention,”[4] as Aaron Shurin puts it — surely left little breathing space for a poetry envisioned, however lightheartedly, as “a profitable exercise / resting on nothing” (3); a poetry whose distinctive address is not a hectoring voice (continuous or otherwise) so much as a generalized consciousness operating in clear concert with the reader, its free-floating surfaces turned toward her or him, collaboratively and generously.

Little wonder, then, that righteous disgust might be defied in favor of a mode that insists on fun, care, and life-giving confusion. If in Champion’s “profitable exercise,” with its dandyish overtones and echo of Francis Bacon’s “optimism for nothing,” we detect the aesthete’s fantasy of play as purity, there is, nonetheless, an implicit ethos. As any reader will quickly sense, these are poems made with such close attention as to suggest the ethical dimensions of a meticulous construction, of a solicitous and vigilant “turning out.”

At times, this “turning out” can feel almost eerie in its absence of authorial or voice-propelled drive. “In the Air” is the supreme instance of this quality:

The exact species picks up background

Using the floor to step out

a bright read surface

Numbers grip, value’s murk

a clear pencil blackens bafflement

“bursts lead to bursts”

Preference is an asterisk

A star dreaming of light

and torn through touch (13)

Words bubble up on the surface of the page as if with self-determined autonomy, uncompelled by the predictable shapes of more vocal energies. Instead, this poem possesses the impersonal, seemingly “factual” detachment of an architectural inscription (which may have much to do with its abundance of declarative sentences):

Angular lassitude

with the “whirr” of a person

nailed to its closed tip a sentiment

yielding states

human jets strip out of the bandshell

pink rubber dovetailed with night haze

unbutton, press release

the ripe cycles got collected

names in their celibacy

questioning space (14)

“In the Air” is so superbly crafted as to raise the almost anachronistic specter of perfected form — whose concomitant risk is, not coincidentally, airlessness. If one or two of the poems in How to Laugh occasionally skirt close to compositional overdetermination (“Fruit Shadows,” “Walls”), then airlessness, cumulatively, can be compelling: it can freight lightness with relentlessness, with an alien intractability that in fact exactly leaves the work “midway between yourself and the viewer.”

One reviewer (Scott Thurston) of a previous collection (Three Bell Zero) has objected to a “unit-unit-unit” effect in Champion’s poems, a reservation that is worth addressing. Firstly, against any monotony such a characterization might imply, we should note a marvelous knack for enjambment and line breaks: see, for example, the delicious placements of the words “desk” and “plant” in these two excerpts — from “Wet Flatware”:

Eye like a silent film cleaning

out the reference

desk, a focus is expecting dust (21)

And from “Colour in Huysmans”:

In method’s bed? Bilious, lurid

in the tap water

Plant. The question of a mask

equally guarded (17)

Secondly, Champion’s brick-by-brick approach never makes for one kind of edifice, but instead for an approach in which every poem presents a test of a previously untried structure — from the swift gesturalism of “Curve” to the spacious yet chatty “Sweating Cubism Out,” to the steady unfolding of a poem like “Colour in Huysmans” or poems that seem almost emptied of motion, such as “Bartenders in Leaf”:

They found the summers lightly boxed

and extracted the goods

A cinnamon species in cold guard

misled by the scent

So they fix themselves a soda

order the rocks with ice

That the eyes did hook

or did the eyes tick (31)

Words — and lines — are handled as bricks or “units” here, but just as instrumental is the carefully calibrated erotic friction that binds them, with such unanswerably evident feeling as to make most poetry of the present seem effortful or formulaic by comparison. This is the generosity of How to Laugh: the poems really are for the reader, “turned out” while never vanishing into meaning or message.