The care and the courage

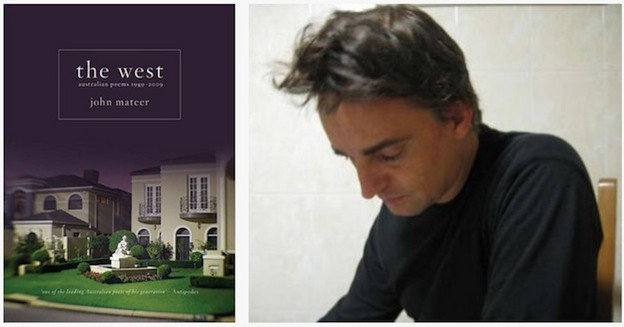

A review of John Mateer's 'The West: Australian Poems 1989–2009'

The West: Australian Poems 1989–2009

The West: Australian Poems 1989–2009

With The West: Australian Poems 1989–2009, his second review selection of his work — following Elsewhere (2007) — John Mateer has decidedly happened to Australian poetry. The impact of his work is one of example rather than stylistic influence: that of an individual writer concerned with their relationship to the world, rather than a quarrel with it or himself, and rather than a self-portrait of sensibility — though quarrels and self do occur in these poems.

Mateer’s use of English makes his estrangement of Australian culture seem like a reflex, making a phrase like “Supreme Court Gardens” sound foreign (“Strolling in the Supreme Court Gardens”). Are poems products of tensions? Or do they rather stream (or step) from a poet in inconsistent variations of bicultural glory? Two qualities that colour Mateer’s poems are the formal and the melodramatic. In this sense the poems are like serious photography: Mateer has a very steady hand. Any extant discomfort is in the viewer-reader.

And yet the poems have a definite 3-D quality also, like a photo being shaken perhaps, or a slowed down accident: where nothing bad has happened necessarily, we’re just checking. I shouldn’t generalise: an early poem like “Outside the Nightclub” has a particular curling around itself that reads a bit like Mateer is asking what enjambment’s all about, doing it and then moving on. (“The sandstone architecture sailed / upward. She asked: “Where?” My / fingers clambered between hers.”)

What makes a Mateer poem? It seems standard enough in some ways: a narrator is somewhere, describing something; something is happening, someone says something banal or striking. The poems are distinct through their attention and their democracy. What happens at the beginning of the poem is as important as what happens at the end — and the end is a happening, not an anticlimax. Mateer’s is an ethical narrator: there to think and question, not to go around having sentimental experiences at Mateer’s expense. If there is awkwardness at times, it is the awkwardness of honesty. The (unawkward) poem of defeated compassion, “Exile,” ends, “And I thought of comparable tortures, / those I’d read of and my friends in / other countries that I can’t imagine. / And I said nothing. I thought: ___.” Another, thematically — albeit subtly — related, is of a dream of being a black cockatoo; its conclusion is: “I / was uneasily considering if I had the right perch” (“Last Night”).

Mateer is fearless in his use of metaphor and simile — like these from a series of poems dealing with bushfire: “I approach a tree, / trying to tell its type from reptilian / evenly scaled charcoal skin: / apartheid?” (“Aftermath”); “Then bushfire // reduced the plantation to ash. After thirty years, like a nation after decades of martial law, bodies unclenching, eyes opening, native seeds are sprouting” (“At Gnangara”); “When the living fire comes, the flames advancing in a straggly line, / like Emergency Services people searching for a lost child.”

The West contains some ambitiously short poems. “On History” is just nine short lines. Even shorter poems make up sequences, or are stanzas or fragments dispersed over a number of pages. While at times Mateer achieves simplicity, the poems are mostly complex — in their composition, their implication (such as the apparently throwaway conclusion of “To Jack Davis”: “You have your own culture. Go back to the Greeks”) — even, occasionally, in syntax: “on the freeway void / and infertile as the European idea / of desert” (“In Real Time”). Mateer’s is at times a bitter sympathy.

Mateer grew up in South Africa under apartheid, a place more difficult than Australia to ignore the privileges of being white. He is unusual in acknowledging whiteness (“between the demolished white man’s school / and the whispering grove of London plane trees,” “The Brewery Site”), and also unusual in his direct address of relations between Indigenous and non-Indigenous, and in his use of (West Australian in particular) Indigenous material. Three great long poems all justify purchasing The West: “The Brewery Site” (a poem of mourning), and two sequences on Yagan, the Aboriginal General: “Talking with Yagan’s Head” and “In the Presence.” As Martin Harrison, in The West’s introduction says, “Much Australian poetry flees from this sort of history.”

Creatures (including humans), things, realities tend to have equal weight in these poems — an equal call on existence; mountains breathe, digging-sticks are “hungry.” This might be the influence of Indigenous philosophy, or maybe it’s just what happens when Mateer writes the world-as-poem, the poem-as-world. There is much more in The West: poems of Melbourne, of sex, of a statesman (white) cockatoo; an ironic “Nocturne.” It’s a book that requires far more consideration than a review can give, and while those considerations may not be in the newspapers where should be, they will happen.

Mateer isn’t pretentious enough to have a “collected” at thirty-nine. Or perhaps he knows it would do his work a disservice to be read in bulk. The West is an attractive volume, pocket-sized for anyone tough or sensitive enough to carry it around. Take The West with Elsewhere and you’ll see, that for range, care and courage, Mateer is as good a poet as we have. Whether we have the care and courage enough to hold onto him is another matter.