The buried encounter

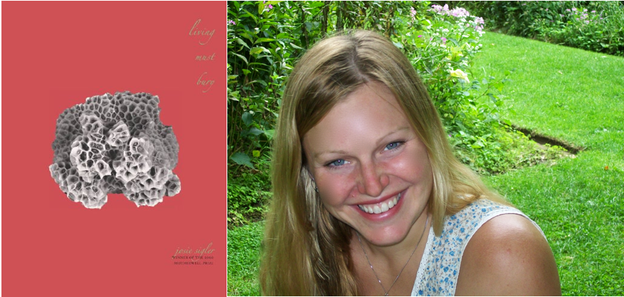

Josie Sigler's living

Living Must Bury

Living Must Bury

In her debut book of poems, Josie Sigler links life with violence, love with loss, and mourning with the natural progression of time. Published by Fence Books as the 2010 winner of the Motherwell Prize, Living Must Bury is a mixture of repeated phrases, historical flashes, and tragic endings linked by the universal experience of living. In these poems, it is the living who must exist in both the present and the past simultaneously, and Sigler’s poems provide ample space for both while challenging us to find beauty in the process of grieving.

Sigler reminds us that we, the living, must bury a host of people, objects, and memories, even (if not especially) the ones that cause us the most pain. The world she creates carries a heavy message for the living. We are repeatedly informed that we must bear the burden of interring all that the dead leave behind. This reality comes through a safe system of poems linked by traditional poetic devices and references to everyday encounters. Designed to guide the reader as we come to terms with the weight we share as members of those still here, Sigler’s book provides a number of lists of what it is the living must bury:

those who are infidels, who in summer once / turned wide circles in grass.

those who would be skewered like hogs if they failed.

those who covet coral

those who will discover trace amounts of urine in their Mountain Dew.

those fighting causes they disbelieve,

those lost, those anonymous, those dream-singers

Through the repeated phrase “those who,” an extensive inventory creates a sort of respite for the reader. Rachel Zucker calls this book a “strange, archaic, 3-D prayer; a lucid palimpsest,” and I agree: Sigler has crafted a work rich with layers. She has moments in which she places religion on top of nature on top of domestic violence:

those who sit through the piercing test for life in Christ’s side.

As in stigmata, the part of the pistil that receives the pollen,

9) the portion of a body that can withstand the hard pew

& after church, my grandfather prying the knife

from our drunken neighbor’s hands & the man weeping

on his knees to the howl of sirens. […]

Sigler frequently employs the couplet to create a meditative space for mourning and remembrance, a place where chanting these memories makes them more powerful. Throughout the book she catalogs violent acts and carnal pleasures, sits them squarely in the memory of the speaker, and recalls relationships and painful places — both her own and those of a distinguished sampling of figures. Dickinson, Plath, Sappho, and Woolf (to name a few) share spaces with Holocaust victims and those affected by war:

those with yellow fever. those whose bones surface like fans,

including those fornicating in places where there is such mud, […]

those shivering on the deck, those who were once stars.

those for whom crumbling is not an instant’s act,

a fundamental pause in which enlightenment:

a mother might sell herself.

It is the union of beauty and brute that brings Sigler’s work to life. She contrasts that which we cannot clearly define with that which we can only define with negative meaning, like the “rusted plow left in winter’s field” or the idea that “hoping love will save you” is a problem. It’s clear that one focus of Sigler’s work is death and its aftermath, but the book also pulls us into a space in which responsibility and desire are at odds.

those wives in church clutching their hankies, their purses, their children.

You know the women who hold onto the world like this.

They’ve married the wrong man, taken the wrong job,

walked down the street during the hour of wolves.

No white-knuckled embrace can save them, no good deeds,

no casseroles left steaming on porch steps.

This contrast provides a familiar dichotomy placing Sigler’s work in a position to redefine the conventions of palimpest-inspired poetry. Moving between figurative language and literal descriptions, the poems seem to have no true beginning or end. This recursive discourse forces the reader to move between the common and the uncomfortable for sixty-three pages. But Sigler does not attempt to trick or deceive her readers; she begins the collection with an epigraph from two poets, Jorge Luis Borges and Sylvia Plath. Together, the two provide an entry point into the idea that Sigler is creating a universe for her readers, one that is quick-moving like Plath’s poem “Getting There,” and one made up of a language Sigler intends to teach us by the end of the book. From Jorge Luis Borges: “If there is [a universe], we must conjecture its purpose; we must conjecture the words, the definitions, the etymologies, the synonyms, from the secret dictionary of God.” And from Sylvia Plath: “I shall bury the wounded like pupas, / I shall count and bury the dead.”

These kinds of moments ground the reader in sometimes earthy and other times transcendent moments blended so seamlessly that one is not sure if the encounter is with triumph or tragedy. And so the living are celebratory in that we continue to enumerate what must be buried while attempting to exist in the moments that Sigler so aptly defines as “the dank smell at the bottom.”