'Besieged by grief'

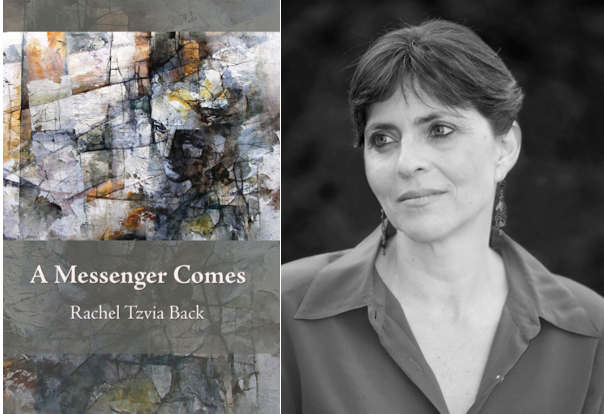

A review of Rachel Tzvia Back's 'A Messenger Comes'

A Messenger Comes

A Messenger Comes

In Rachel Tzvia Back’s collection of poems A Messenger Comes (Singing Horse Press, 2012), the poet, like a biblical Deborah bearing a torch, arrives to illuminate the dark, devastated, and devastating space of grief. Following the deaths of both her father and sister, the poet is spiritually “called” to apply language to mourning. This calling is revealed in the epigraph to Messenger, a passage from Leon Wieseltier’s Kaddish, the profound elegiac work for his own father, which also gives the collection its title: “A messenger comes to the mourner’s house. ‘Come,’ says the messenger, ‘you are needed.’ ‘I cannot come,’ says the mourner: ‘My spirit is broken.’ ‘That is why you are needed,’ says the messenger.” In the first section of poems, “The Broken Beginning,” the poet imagines grief and grief’s counterpoint, love, being formed with the creation of the world itself:

(In the beginning)

In the beginning

it was sudden —

the world

that wasn’t

yet

all at once

emerging

out of formless void —

space

of the infinite

broken

into pieces — God

retreating

to make way

for perfect human

imperfection:

Adam and Eve

dreaming

in the beginning

of a world that wasn’t

and wasn’t yet

broken either (13)

The poet must pave a way through the world after it, and she, are “broken” — after grief has befallen humanity inescapably: “Thus the sudden rift / opens // to define us — After and / then // Before” (66).

Many themes of Messenger — among them Judaism, the Bible, Israel, and Hebrew — are prominent in Back’s past collections, On Ruins and Return (Shearsman Books, 2007), The Buffalo Poems (Duration Press, 2003), Azimuth (Sheep Meadow Press, 2000), and Litany (Meow Press, 1995). Back was raised in Buffalo, New York, and studied at Yale and Temple universities, but has been living in Israel for three decades. Her work is thereby dually informed by American traditions (Emily Dickinson, Walt Whitman, and Adrienne Rich make appearances in Messenger), and Israeli ones. In an interview, Back has discussed the complexities of her choice to reside in Israel: “I have a great passion for Israel, even now — a passion for the Israeli landscapes and sensibility, for the rhythms of the Hebrew language, for the ancientness of the culture, and its raw newness too. My heart feels most connected to itself in Israel — I feel most myself there.” Indeed, Israel, Jewishness, and Hebrew permeate Messenger; for instance, in an image of olive trees (55); in a poem that enumerates the names of sacred Jewish texts, some invented by the poet herself (51); and in a poem which meditates on her father’s passing using the English letters a-b-a, which join in the last line to spell the word Aba: “father” in Hebrew (39).

Back’s work has long been engaged in and concerned with the atrocities of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. As Andrew Mossin writes in his 2008 review of On Ruins and Return, Back has sought to bring a new mode of “seeing” to this conflict. Her poems, in the tradition of women poets of witness, such as Rich, Muriel Rukeyser, Carolyn Forché, and Alicia Ostriker, frequently juxtapose the personal and political. In On Ruins and Return, this is achieved when the lyrical “I” is used in the service of describing a disputed, embattled land: “I live on the ruins of Palestine.” Sporadic references to conflicts of the region also appear in Messenger. In a passage from the long poem “Lamentation,” the poet writes about a dream in which her elderly father climbs “a grove of old olives” atop “the wounded land”:

(21) Dream inquiry (2)

pillagers have gathered

stones from the wounded land in

their angry hands and when

they raise weapons for harm

my father lifts both his arms

into the unblemished blue

a bird

spreading white woven wings

wide

over us all

in the ancient grove

steadfast

sun glistening

still through the wings even

after

he’s gone. (55)

As her father morphs into a white bird, presumably a dove, spreading his wings “over us all,” the poet thus envisions his spirit bestowing peace to country that is torn, but their home nonetheless.

In Messenger, however, the poet primarily writes of grieving in a way that is personal, rather than political:

Every moment of every day and

Every night I am

Besieged by grief

Closed to any loss but my own. (97)

The last lines of this poem (from the section “Elegy Fragments”), display a turning inwards, away from the Other, following the poet’s terrible loss. In Messenger, the poet’s sense of self is so utterly shaken, shattered, that she writes (in another section of “Lamentation”) of being embodied by loss — “at” and “in” loss:

(8)

Cut loose (not

yet) we are

at

a loss

we are

in

a loss

and

lost in

lost to

what

we are

bound to

bound by

now slowly

losing

in days

and numbered

hours. (42)

The series of enjambments affirm the harsh rupturing of the poet’s selfhood and the life that was known to her. With the use of the plural “we,” she reminds us that while this rupturing can be shared to some extent, we must cope with its impact alone; in the case of Messenger, through a dialogue with one’s own poems. Though the poet certainly never addresses a higher religious authority (such as God), the incantatory poems are forms of "secular" prayers in themselves.

The poet’s father and sister occupy their own sections in the collection, highlighting the individual significance of each. In the first sections of Messenger, the poet writes of her father, depicting him as larger than life: “Six feet tall broad and bearded / traveling a world / (in a hospital bed) // professor and scientist / (huddled under / the covers)” (40). In a later poem, Back writes of his “wide-armed gestures, voluminous / stories detailing each / memory in grand trajectories / of arced blossoms” (65). In the final section, “Elegy Fragments,” Messenger turns to the early passing of the poet’s sister: “My sister died / in mid-summer, in the middle // of the night, in the middle / of her life” (87). In a subsequent fragment, the poet revisits the notion of shattering, or coming apart, which is so prevalent in the collection: “Steadfast / sister, there is steady / unravelment / in the vastness of your / absence” (89). Back courageously writes of the longing, even guilt, that can accompany the death of someone beloved, “How I try, and fail / to return you to us // in every word and verse / ever faltering —” (90). Although the poet cannot write her sister (or father) back to life, solace is found in the vision of her sister (like her father) as a bird:

Sometimes in the birds’ flash

of white-winged flight

I think I see you

delicate delicate

your lovely name

in that winged instant written

across all the skies (100)

As is often the case in Back’s poetry, layers of meaning are revealed with a knowledge of Hebrew; here, the twice-repeated word “delicate” (perhaps echoing the birds’ wings flapping), is the English translation of her sister’s name, Adina, to whom the section, and the book in its entirety, is dedicated. Thus, Adina’s memory inheres in English and Hebrew, the two languages from which so much of Back’s writing springs. In the last elegy fragment, we thankfully encounter not a contrived notion of grief’s finality, but a recognition of its perpetuity:

As though I am not

in Secret and

with every breath

Waiting for your return. (101)

Readers are advised to explore the moving, well-executed poems of A Messenger Comes. If the book begins with the poet being called, Messenger is a remarkable answer to this call. By hearing Back’s words, we become braver in the face of our own grief, as well as love, two sentiments the collection wonderfully articulates: “Enduring / love: How // is it to be endured / in your absence” (93).