'alchemy's new materials'

A review of Jamie Townsend's 'Shade'

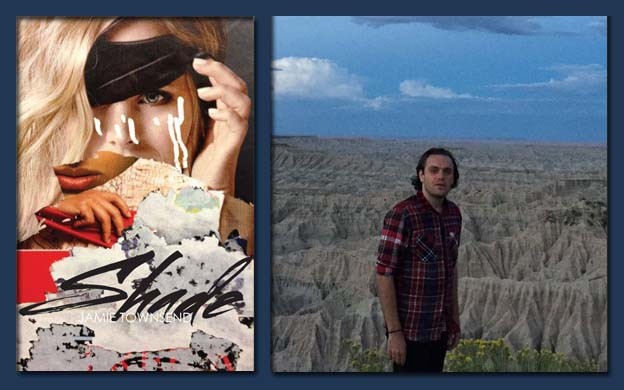

Shade

Shade

Jamie Townsend’s debut collection of poetry, Shade, continuously turns for us a promise of utopia that is as perpetually deferred as it is exhausted. Much like a mixtape or a news ticker’s scrolling forecast of weather and stocks, Shade traverses contiguous anxieties about what capitalism renders immaterial and how optimism becomes militarized, with Townsend trailing who (or what) follows us from the streets into our throats, from our dreams into the law. That is, Shade raises again for us “the problem of language & desire — its star maps bound around limbs / — histories we speak ourselves into.”[1] But these histories are, in turn, qualified and differed endlessly as “ecstatic positions where words eventually circle but never / fully penetrate” (14).

The poems of Shade, then, are concerned with — and especially by — transformation, intuiting in that capacity to change a power that is used both for and against, though the wielders and targets of this power remain hidden. Take, for example, the opening lines of the collection, from the poem “Paradise Now” — a list of magnificent things without a clear delineation of the direction of agency or reception:

the real shit of alchemy’s new materials

the historic precedent found in early music video special effects

the ghost mixtape as cipher , making urban Midwest from Yokohama , Sophia

Coppola making Emma Watson teenage SoCal , making heaven together in the dark

outside the luxury condo (7)

Within the alchemical matrix of Townsend’s poetry, a soundtrack has become a secret code; a Japanese port city has become the United States’ heartland; Emma Watson, UN Women Goodwill Ambassador and former star of the Harry Potter franchise, has become an upscale small criminal; and bourgeois life has become (or has been revealed to be?) a hell ensconced in a developer’s wet dream. This all leads up to one of my favorite images, what must be an homage to the lush romance of John Wieners: “the tonal range of names cried out in bed, their duration & emphasis / the precision of the vague & its central act becoming nonlocatable / the pink roses by the cash register” (9).

In witnessing the twisting of these places, people, and even fantasies, Shade suggests that paradise can be intuited, if only fleetingly. Our “paradise now” grants us glimpses of the protean shimmering within processes of transformation, often attaining the lyric pitch of liturgy. Consider this breathless moment held in a long stretch of unpunctuated prose from a long sequence of poems titled “Thrown Shade”:

the daily movements of my fellow residents have become theoretical opaque & elusive as if writing about them & myself instead of providing greater clarity & dimension has instead enacting a sort of parasitic drain rendering their forms amorphous shriveled bled out to grey scale & the more i fill up these pages with cyclical attempts at dismantling then reenvisioning modes of lust loss friendship the modes of any life together the more concerned i become with the process itself what my body is doing next to the coffee machine for hours (65)

In passages such as this one, Townsend displays his apprenticeship to the ecstatic prose of New Narrative writers such as Robert Glück and Bruce Boone, in addition to the sexy, body-troubling science fictions of Samuel R. Delany. Still, Townsend makes significant breaks from his mentors in Shade. Glück’s and Boone’s first major works were conceived contemporaneously with the swan song of gay liberation, a singular record set between the door closing on the gay 1970s and opening upon the AIDS crisis and turn to neoliberalism of the long 1980s. Townsend’s poetry sits more awkwardly in relation to any liberationism, optimism, or utopianism. The attitude of Shade — wary as it is of embracing completely the promise of the pop song, wherein we’re “feeling it & offering continuity like / a tongue inside the routine” (50) — is one where good (political) feelings cannot be trusted. Whereas Glück and Boone could rest their imaginations on the notion that the future was tenable, Townsend holds the imagination itself in suspension, turning over again and again the promise of a better tomorrow to check it for malware and Trojan horses.

Townsend’s fixation with deferral and suspension can also be read at the level of form, where clauses refuse to close off and commas and dashes create nesting effects, delaying the satisfying arrival of a final grammatical unit. There’s no (syntactical) completion or individuation, as phrases, lines, and sentences fall off into one another. Bodies become indistinct, only rarely popping up with proper names and subject pronouns. Consider the beginning of “Heartbreaker”:

Antony sings crazy in love and the world changes completely

each inflection draws out sex as portraiture in invisible ink

your flannel won’t save you but the gold lamé bikini bottom

rises from the pool , lights the apex of your arc , & draws together

a swarm of celestial parasites glowing in the greater demimonde

a vintage American Apparel model backlit by subterranean grotto

inverted Mimi diva of the tri-sex self-reflected blinking ,

closing the camera , looking away

the song obliterates signature (103)

Perhaps in this moment without particularity, without individual signature, awash in fantasy and sensation, we are offered a new mode of feeling. To me, this is the shade of Shade: the space apart from all the boring hours in the aforementioned developer’s luxury condo, in which pleasures and ghosts of pleasures congregate. Townsend’s poems speak to a relation to power and pleasure that is shaded — hidden, obfuscated, cloaked, smudged. This is a queer relation to power and pleasure, absolutely, but one that has been assimilated in a very recent past, the youth of millennial poets, so that now the police and the state also have a vested interest in subjects consolidating themselves even in their shaded desires. At many levels, Shade captures this turn in identity politics, especially queer ones.

Here I’d like to interject that, ostensibly, the title of this collection could also refer to a now-popular slang term that finds its roots in the documentary Paris is Burning. In this film, drag queen Dorian Corey quite memorably defines “shade”: “Shade is I don’t tell you that you’re ugly. But I don’t have to tell you because you know you’re ugly. And that’s shade.”[2] Yet I’d argue that Shade says less about any past aesthetics of sexuality, race, or performance than the title suggests. Instead, it records a contemporary meditation on relations of power and the swift, effective occlusion of these relations via popular culture — a prime engine in the regulation of optimistic production and consumption. Townsend urgently reminds us that Antony Hagerty’s cover of Mariah Carey “obliterates signature” — and thus, surpasses the necessary individualism of neoliberal capitalism. If Shade is a song, it’s a cover, knowingly dissonant with the monolingualism and atomization of the smash-hit single.

In this relation to the mainstream, Townsend’s work is reminiscent of many of the so-called post-conceptual poets (e.g. Felix Bernstein or Andrew Durbin), all of whom queerly appraise and reference pop culture to produce a patina of anticapitalist critique. Still, it shouldn’t be overlooked that Townsend takes for his model of queerness the gossipy, ribald sensibilities of Glück, Boone, and Delany rather than, say, the superficial dandyism of Andy Warhol. The difference is that Townsend’s poems register the enchantment of the commodity — the way it gets under the skin and shoots around the brain with a promise of satisfaction. Shade knows something of the utopianism in allure that leaves the speaker of these poems not aloof or rarified in post-conceptual smugness but vulnerable and stupid before desire, even when he knows better. For example, consider this moment in “20/20,” Townsend’s meditation on Whitman’s America:

i read about fields of light & music like crystals , desperately wanting new things

i buy a shirt in a pattern called KASBAH & listen to Lou Reed sing about Coney Island

for money to buy junk — …

i buy a shirt in a pattern called LOW END cream with yellow roses to petition the sky —

i buy black denim & cannot remember my dreams —

from above huge herds of beasts are the first things we can see , grazing in the light , their

variegated coats shining — (96)

In other mouths, this out-of-control feeling of superabundance might simply be an argument for a triumphant euphoria, but in Shade, we read how pleasure — and even pleasure’s supreme manifestations in satisfaction and ecstasy — is taxed, capitalized upon, even routed back against itself. Townsend writes, “like we’re spoken into existence for now — spoken into each other but ourselves remain (are forced to remain) locked inside aphasia—” (13–14). The pleasure of Shade is attuned to this play of the visceral among the slipstream of the denotative — that we have little to no mastery over that which pleases our tongues. In the face of such a panoply of delights we find ourselves immediately overwhelmed by everything on display.