'Really, music was the cause of it'

Interview with Russell Atkins, June 2, 2016, at The Grand Pavilion, Cleveland, Ohio

Note: The poet Russell Atkins falls through all of the cracks of postwar art history.[1] Living in Cleveland, outside the geographic centers of the art and publishing worlds; caught between modernism and the postwar avant-garde; publishing in small press journals; writing generically indeterminate concrete poems, essays, and operas. In terms of medium, his work belongs to music history as much as to literary history. Politically, he is located simultaneously in the avant-garde, behind the times, and outside the Black Arts Movement. Most of his papers were destroyed by a court-appointed guardian, so his archive is slim. The story of that destruction connects his life to the larger story of the gentrification of Cleveland, the undermining of the Black middle class, and the challenges of structural racism he faces as a Black artist with no living family.

Russell Atkins was born in 1926 in Cleveland and still lives there. But through small press circulation, he participated in a larger poetry scene. For a time, Atkins enjoyed a national and even international reputation. He corresponded with Langston Hughes, Marianne Moore, and Clarence Major, who all championed his work. His poem “Christophe” was published by Langston Hughes in The Poetry of the Negro 1946–1970. The early concrete poem “Trainyard at Night” was read by Marianne Moore on the radio. He is mentioned in Stuckenschmidt’s Twentieth Century Music (he was also a composer and music theorist). He is perhaps best known as the editor of Free Lance, for many years the only journal dedicated to publishing African American poetry. The first issue appeared in 1952 with an introduction by Langston Hughes; it ran until its twentieth volume was published in 1980, a nearly unheard-of longevity among small press magazines.

He began publishing his own work in the 1940s and was influenced by modernists, so by the 1970s an antiquarian flair made his writing anachronistic and uncool. He was writing what was clearly concrete poetry, although he didn’t call it that, as early as the 1940s, thereby predating all other anthologized poets thus far credited with that modernist innovation. His experiments with abstraction put him at odds with the Black Arts Movement and have marred his reception. Exemplary in this regard is a review by Johari Amini of Heretofore in the September 1969 issue of Black World/Negro Digest that describes two poems about historical Black figures — Henri Christope and John Brown — by saying that the poems “are written as if by a Victorian era observer, and not a blkman dealing with his history as he should be about doing.”[2]

His reception has arguably suffered from the experimental nature of his work that extends across genre and media. He wrote music theory and psychological theory, publishing these difficult essays in Free Lance. His 1955 manifesto “A Psychovisual Perspective for ‘Musical’ Composition” argues that music composition fundamentally follows a visual logic, and accordingly should be written for the eye rather than for the ear.

His work allows us to draw some new lines between key terms of twentieth century art: concrete poetry and musique concrète. Both were self-reflexive gestures that emphasize the physical material of a text. The former was a widespread and diffuse movement unified by a concern with the appearance of language on the page or other substrate. The latter consisted of experiments with recorded sound and “tape music” by Pierre Schaeffer that would be formative for later iconoclasts like John Cage.

But Atkins’s “Psychovisual” argument defamiliarizes music and withholds the sonic dimension of his poetry in a way that can’t be accounted for by framing it in terms of concrete poetry. The scope of his claim is potentially far-reaching, its purview exceeding the bounds of music composition. Is this distinction specifically about aurality and visuality or is it about the sensoria in general? Does it entail a change in the object of perception or in the perceiving subject as well? Is it about notation (the document) or about listening? The manifesto attests to the possibility of a defamiliarization of aesthetic practices via the mutation of the senses. In this reframing, rhetorical force exceeds the topic of musical composition per se and becomes about the necessity of reframing itself. It is a radical voluntarism about perception, one that raises questions about the material conditions of the imagination and the limits of such voluntarism.[3] The interest in materiality attributed to concrete poetry may in the case of Atkins be properly registered in this dynamic of questionable, contested, and unequally distributed transcendence (in other words, in a sociopolitical rather than merely typographical materiality). A commonplace of aesthetics, following Walter Pater, is that all art aspires to the condition of music (that condition being the unity of form and content); Atkins disrupts this unity at the level of the musical composition by staging the conflict between writing and sound, to disrupt the association between form and sense as a consequence.

We have paradigms for understanding a “visual” music. Musicology constructs a long history of experiments with the visual dimension of music notation, and in particular has documented and theorized the postwar avant-garde that constitutes Atkins’s immediate context. But what happens to the sonic dimension of the music, if we follow Atkins’s insistence? It is fugitive. The result of defamiliarizing the sonic dimension is that it is no longer immediate, and no longer available as a naturalized ground of cultural politics. The manifesto is a paradoxical performance of obscurity: the insistence that music is in plain sight, showing with one hand and obscuring with the other. In the distinction between audibility and visibility inheres a racial politics; each of those terms carries immense discursive force in the context of Atkins’s writing during the early Civil Rights movement and through the Black Arts movement. Atkins destabilizes visibility and audibility as the two central tropes of cultural and racial politics: the manifesto is a “discrepant engagement” with musical composition and sense experience, and thereby with racial politics itself. By obscuring the sonic dimension of music (and by extension, I argue, of his poetry as visual compositions) Atkins contests the paradigms of avant-garde music composition, concrete poetry, and Black aesthetics.

Russell Atkins’s poetry and theoretical essays show that genre indeterminacy has particular stakes in the history of African American literature, namely that it runs counter to an imperative of representational stability and legibility that served as a form of social control. Atkins’s main mode of resistance was the pursuit of abstraction, a mode that has a contested history in African American culture. Indeterminacy at the level of genre is linked to theories of the indeterminacy of the senses in Atkins’s work, which is further linked to resistance to political overdetermination.

The poet Russell Atkins, formerly editor of Free Lance, is now ninety years old and lives in a room at the end of a long corridor in an assisted living facility. His memory, contrary to his self-deprecating remarks, is extraordinary. I found him to be charming and quietly hilarious, with a subtle but cutting sense of humor. His roommate was gone on the afternoon I came to visit, and so we were able to speak undisturbed for two hours (except for a moment when a nurse came to give him his pills). The staff seem to have recognized, based on the comings and goings of his visitors, that he is a person of some distinction. The majority of his papers were destroyed a few years ago, and I hope that this record might go some way toward reconstituting an archive. My thanks to Diane Kendig for her indispensable help in arranging the meeting. — Cameron Williams

[I begin by steering the conversation toward his early innovations in concrete poetry and asking after the connection between those poems and his musical activities. What becomes clear is that he belonged to a moment where his early formation was influenced by turn-of-the-century poets like Edwin Arlington Robinson and Amy Lowell, but he could then go on to look to Ezra Pound and the modernists for ideas. In other words, he belongs to eras both before and after modernism, since his career has spanned so much time.]

Russell Atkins: Little magazines or literary magazines are hard to follow. There’s a magazine in France called Message, and then Italy called Botteghe Oscure — Dark Street, I think that’s what they translate [to]. And then a publisher in Germany named Janheinz Jahn. Did you, have you ever heard of him? He came over here to meet me, but … that was in several of these anthologies, I don’t know which one. And that was kind of an around-Europe publication. Then I find that you publish one book in England by Greenmount publishers. Do you have that record?

Cameron Williams: I have … I don’t have the physical book but I’ve read the reviews of it.

Atkins: Somebody reviewed it?

Williams: Yeah, back in the day, when it first came out.

Atkins: That was some time ago. And due to the unfortunate treatment of my works … when Kevin took over the idea of the Unsung Masters,[4] [it] left me with certain, well, lack of any way to trace all of that stuff. What particularly would you want to know?

Williams: Well to go back to your earlier comment about concrete poetry being this pretty widespread movement; it’s a strange movement in the sense that several people who …

Atkins: Well the word “concrete” was never too clear because some poet in Brazil was assumed to have invented the term. In Europe — I forget to whom it was attributed — it might have been any of the avant-garde in poetry: Francis Picabia … who else… Well back here in America I guess you would have to include certain American poets I think that contributed to it. William Carlos Williams, everybody’s heard of that. And Pound. You could go on because — in the magazines that I saw around — the name was attributed to poetry that was thrown around the page, you might say. That was thought to be concrete. But I was never sure of what they meant by the term concrete. […] I don’t know what the Brazilian poets …

Williams: There was a group of them, the de Campos brothers and Pignatari … they were also, if not composers, they were interested in Webern, and were reading Anton Webern’s work.

Atkins: Oh, the composer? Well actually, my beginning with concrete poetry was just as Kevin said, in the early copies, anybody can check them, I guess, I don’t know, that’s the difficulty of it. In the Beloit Poetry Journal, I don’t know if you’ve ever heard of that, a magazine called View, which

was —

Williams: So which was the earliest one that you remember working on, or how did you …?

Atkins: How did I decide to become a poet? That’s what they used to say.

Williams: That, but also, “concrete poetry,” since as you say is this slightly amorphous term, why were you specifically interested in …?

Atkins: That was attributed to me by the Beloit Poetry Journal. We’re tracing something that — there were several books written on poetry, I can’t name the author but he wrote a book on Egyptian poetry as an early example of poetry with pictures. Then you didn’t hear much more. But I can’t think of his name. Then later on, another book appeared on poetry in the nineteenth century on vases, you know, flowers and so on, and the poems were arranged, influenced by those arrangements. You’ll have to look them up in the library.[5]

Williams: You were reading those in the 1950s?

Atkins: No. In America, we were not generally considered to be, Americans were looked [on as being] kind of secondary. I don’t mean race problems, I mean American culture in general was thought of, as some Frenchmen found, barbarous. And that was, you might say, the feeling that American poetry was a kind of an imitation of English poetry. Until Pound and Eliot came along and changed that. But I would say that these poems by me were written in the late ’40s. But they weren’t … putting the term concrete to them, you can’t give me any real …

Williams: That was an aftereffect.

Atkins: Yeah. Now the fellow who wrote out some biography of me …

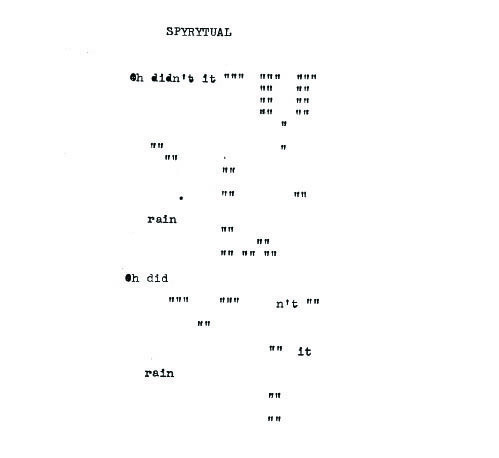

[Here, I show him a reproduction of a very unique concrete poem: in 1966 Atkins published a chapbook containing a single poem, Spyrytual. It harkens back to Apollinaire’s calligram about rain, “Il Pleut,” but looks quite different. It is a song with two lines, repeated — “Oh didn’t it rain, Oh didn’t it rain” — among a scattering of quotation marks. “Oh didn’t it rain” is an African American spiritual performed often and in various arrangements. It demonstrates the prominent role abstraction plays in Atkins’s reconstruction of past material.]

Williams: These are some printouts of your poetry books. I have some chapbooks. There’s Spyrytual. I have a question about that one in particular. This chapbook, which was published, which was just this one poem, as far as I can tell.

Atkins: Do you know where it came from?

Williams: It says it was published in ’66.

Atkins: Oh Spyrytual. Actually that came as a result of music. As you know I was going along with music at the same time. And you might say that music had some impact on … and I am more or less a composer. We can look at that later.

Williams: But this one I was curious about for a couple reasons. One is that I was reading that you composed many of these works that you called spyrytuals but that this is the only printed one.

Atkins: No, they have that wrong. What I composed as spyrytuals was music. I had planned, I forget who first told me. I have memory lapses, what was the question?

Williams: You say that there were other works you were calling spyrytuals.

Atkins: That was music. And this wasn’t entirely accurate. Because I gave the spelling … I used Chaucer’s Middle English. Because the intention was to … “spiritual” was an American African style, but when I took it over, to add to my spyrytuals, I chose to spell the thing as in Chaucer: the “i” is a “y.” I think that’s because I, as in music, when some composers added different things to their compositions, they put titles on them that belonged to different verbal effects. Now I can’t at this moment think of any but … this wasn’t the way I originally had the poem. And I’ll tell you what happened here, someone — who edited the magazine this was in?

Williams: I’m not sure, as far as I could tell it just was issued as a one-off thing.

Atkins: Oh, Sunflowers, that was d. a. levy. But levy was just a kid in comparison to me. I’m ninety years old. In fact, a lot that goes on, you’ll have to remember that even I can’t remember. He joined Free Lance magazine, the workshop. And at that time I was closely involved with the Cleveland orchestra, friendships you know. I think, I don’t want to sound disparaging in any way, but I think levy saw that I was getting kind of recommended as a typographical poet, yeah, Free Lance took over the idea that, and at that time […] there was a magazine in Mexico, I forget what it’s called, but you’ve probably heard of it, in which some of the typographical ideas were circulating, so couldn’t be really said to have invented the form, some people had never seen poetry under the American aegis published like this you know. So in a way, Pound somewhat you know, and Eliot in a secondary sense, gave a new meaning to American poetry that Europeans had claimed was imitating Europe. The early American poetry like [Edwin Arlington] Robinson and Amy Lowell that we no longer — I think Pound influenced us more to adopt that with his Pisan Cantos. I don’t think that it was anything that I particularly claimed credit for. But somebody may have claimed it for me.

Williams: On your behalf.

Atkins: I simply joined the idea. But why the term concrete, I never understood either, but there was at that time a musique concrète. And somebody may have decided that poetry in some way looked like or resembled in the way it’s formed. In other words, we’re dealing with a whole era of music, music and poetry, there were American poets who were first … when this magazine came out published by a fellow who was a member of the group that’s called Muntu poets that’s going now, he wrote an article on me in which he sort of made the statement that I’m making to you now, that American poetry had a kind of influence by the … I don’t know where we can put the influence of it. Where did you first hear that I had? Well what is the point that you want to make in what you’re writing?

Williams: I was starting with your music theory as a kind of jumping-off point, and this idea of the psychovisual and trying to use that to understand —

Atkins: Well, I am very disappointed in that, because when I moved, that disrupted my whole thing, my house …

Williams: All your boxes of papers.

Atkins: Kevin saw them, because I was still living in, what was that the name of the place?

Williams: But before we move too far afield. You were saying that originally this didn’t look the way it was arranged here by levy.

Atkins: No, I used, what are they called? [Motions.]

Williams: Slashes? Oh, and he’s replaced them with quotation marks.

Atkins: The printer replaced them. And I never did really approve of it, but there wasn’t anything I could do about it.

Williams: Well what I thought was interesting about this piece — and tell me if I’m going at it the wrong way — on the one hand you’ve taken this spiritual, “Oh Didn’t It Rain,” which had many other verses, that’s just one line, and combined it with something like, to me it looked like the Apollinaire poem “Il Pleut,” where he has the words coming down like rain.

Atkins: Who does that?

Williams: Apollinaire.

Atkins: Oh, Apollinaire, the poet you mean. Well, actually Apollinaire was not much of an influence on my — but he was already an influence, so … what do I know about Apollinaire… did you say Apollinaire had written one with rain like that?

Williams: Mm-hmm. I mean, the similarity is only in the theme of rain and the idea of visually arranging the poem.

Atkins: I’m trying to think … but Apollinaire did have an influence after all. People have to realize that I did all this when I was rather young. I’m ninety now. That means that a lot of it happened, to really put it … you know the magazine called View? I knew Henri Ford and Parker Tyler, they were the editors, there’s a booklet, it was written some years ago, an homage to — what was his name?

Williams: Ford?

Atkins: Haha, shows what’s happening to me. What do they call it? Homage to Ford. In which I contributed a poem. But it was a poem written in ’47 for View. Which was actually, it was really the beginning of my actually becoming what you might call a professional poet, sending around to magazines and appearing here and there. So it’s all kind of scattered in a way and naturally that was one of the places where I first started reading Apollinaire, I have something here from Apollinaire, I don’t know where I could have put it … [Shows photograph.] The fellow next to me is a very well-known composer, or he was before he died. Hale Smith.

Williams: And you collaborated on a few things.

Atkins: Hale wrote a commemoration on the death of — what was the head of the Cleveland Institute, I forget his name, it is in there somewhere. Rubinstein. When he died, Hale wrote some of the music for the — I guess you know Karamu. In the early days of the ’40s, I did some poems in the, in that typographical, which then later became concrete, and it went on to become what else, wasn’t there a third one?

Williams: I’m not sure. Because concrete as an international moment boomed in the ’50s and then quickly passed.

Atkins: But there was an earlier version of it, I suppose that would include Pound, and cummings and William Carlos Williams, there were an awful lot of names popping up at that time, of which Apollinaire was, some of his work was appearing in View magazine at that time. In fact, Zachary Scott, the movie actor, what’s-his-name’s sister married, you haven’t got it in that magazine, the one what’s-his-name wrote. Well in some of those things that were coming in and out in the middle ’40s and so on, she married Zachary Scott, but I didn’t know that until I contributed this poem to what’s-his-name who was commemorating, who wasn’t dead, he was still alive, he wanted to do this magazine. I am sorry I lost track of that, it must be in the things.[6]

Williams: I can look up these things later.

Atkins: Well I guess you can, but some things you can’t. The Beloit Poetry Journal for example, which I contributed to the development of, because some of my developments were … its hard to even show it, I don’t have it, anything to show. But anyway, that’s when I thought of myself as being a professional poet or writer, and then when Parker Tyler took over he became the editor.

Williams: Well this one I know was published in Beloit. “Prelude and Nocturne,” or “Nocturne and Prelude.”

Atkins: Well let’s see, it might be the one. Who had these, where did you get this from?

Williams: I tracked down issues of Free Lance in the New York Public Library. Some of them are missing, so I had to go to different places and photograph them.

Atkins: Well this was a poem written, oh boy … a poem about changing from night into day, that sort of thing. It was pretty obvious. I was doing it specifically because I wanted to write a poetic version of night into day. That’s what this was. And Beloit Poetry published the night into day version, which, I don’t know whether they really appreciated it or whether they weren’t happy with it, they sounded … well I think that was the most, I think that it was a startling version of the technique. And somebody may have, one of the poets who was still alive, who had his magazine at that time, might have referred to it as typographical. These things in the world of art are very difficult to pin down because they’re all done by different people in different places in magazines that appeared only once or twice, and we all thought Free Lance would be one of those. But it wasn’t; turned out by having a good friend in the middle of it, turned out it ran for almost thirty years. For a little magazine, that was almost impossible at that time. But he did it by, he was a librarian, and by getting different jobs in different libraries, he was usually given the editorial department somehow, and he used it to help keep Free Lance going. And it ended up with only myself, he and myself, because everyone died out after thirty years, you can’t expect anything to last for that long.

Williams: So when you were working on Free Lance what did you think about its relationship to other small journals?

Atkins: Well we were very much involved with them. Because in those days, little magazines were supported by what they called the magazine exchange. They send you your magazine saying, “we realize that you publish a magazine, how about sending us one back?”

Williams: So quid pro quo kind of thing.

Atkins: It became a source of … a bag of poetic … like Beloit, much of it was, much of it represented what poetry was doing then. Anyway that’s how we stayed alive for thirty years. I can’t believe it myself when I say it, you know. Some of the magazines we appeared in, that we appeared as, sometimes there were only about one or two issues. In fact, View magazine was produced and had people like Edith Sitwell supporting it, and Charles Henri Ford, even that passed out. I got in in ’47, under the, it was suggested to me by Langston Hughes, you’ve heard of him I suppose. I wrote, and they wrote back, and they were interested, and I was working on this at the time, and that’s how that got started. It was situated in such a way that, I hadn’t appeared in that kind of thing done at that level, hadn’t really appeared in the American magazines.

[Here the conversation shifts toward a discussion of music: his own career as a composer, his music theory, and the influence of musical ideas in his poetry. The importance of Wagner to him suggests, I think, approaching his myriad interests as facets of, in Wagnerian terms, a Gesamtkunstwerk, or total work of art.]

Williams: So what was your thought process in coming up with these types of poems, regardless of how they later got labeled, and compared to other work? What were you working through?

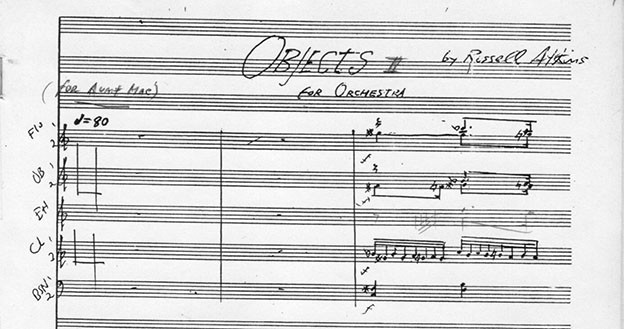

Atkins: Really, music was the cause of it. I guess I might as well show you some of the pieces that … in music I started the term. Some things I did do earlier. Well let’s fix it at the time. When Hale and I became very good friends, he was very much under the influence of Schoenberg’s twelve-tone writing you know, and that I suppose, that some of the things that Hale suggested when we talked over the poetry, you know and so on. Hale did not write poetry, he wrote music, but he did suggest certain things to me. That was a very early period, to me, that was back in the ’40s you know, that he and I were good friends, he was busy becoming a jazz performer.

Williams: So doing both serialism and jazz. You say that he was influenced by Schoenberg and doing jazz, not that they’re incompatible, but that to do both is interesting.

Atkins: Yeah, he was at the [Cleveland] Institute [of Music] studying with Marcel Dick who was the leading, one of the leading composers there. But there was very little chance to get published with music, he wrote real music. Well, I’ll show you my attempt. So all you had more or less was the exchange of your friends. Hale was very well informed, since he was at the Institute. But for a living, he did jazz piano, which is what I should have done, I don’t know why I took such a rigid course, but I became a so-called classical music extension composer, which in the way I did things brought music into it. Music is part of psychovisual theory, and part of developments, I can’t really tell exactly when I began all the ideas, or using some of the ideas that were then current. But that’s it.

Williams: So what were the ideas that you were exposed to? Were you also exposed to Schoenberg, or was that just coming from Hale?

Atkins: I composed myself, I did also compose. Hale was really interested in classical music, but then so was I. I started music with my mother, but orchestral music I was in the beginning of it, not in the beginning anything that was good that I had done, just in the atmosphere, while Hale was pretty well informed.

Williams: Who were the big influences, then, in the classical world?

Atkins: Oh, well, of course that became … Webern was one, but that was a little later actually.

Williams: Because he was Schoenberg’s student I guess.

Atkins: But that is, getting to that point later, but there [were] quite a few of them. Schoenberg and Webern, and there were still the effects of Bartók, and of course, without influencing in a direct moment I could mention … the biggest influence on me, and most of the people at the time, was the inimitable Wagner.

Williams: So how were you exposed to these composers? Through concerts, or could you get the sheet music, or …?

Atkins: Oh well that was easy, I became friends with the Cleveland Orchestra. My music teacher at that time was Becky Schandler. [Hyman Schandler] was the founder of the women’s orchestra. His wife was very much in the musical scene, naturally she was. I’m not designating some of the specific things I guess I should, anyway she was in the Hebrew faith. She kind of took me under her aegis. I had a very good musical background following her advice here, she taught music but I didn’t continue it. Well that’s another different thing altogether.

Atkins: [Of his operas] Well the chance of ever having them performed was out of the question, because opera, even the Met struggled with money to put on the things, and mine nowhere. And even Hale, well Hale didn’t bother to write an opera, he just thought mainly of the music, like Debussy and so on, well there were so many names.

Williams: When he was talking about Schoenberg enthusiastically to you, and you say that you are working though those ideas in the poems, how did that translation work?

Atkins: Well, many, for example Wagner, Wagner’s music was highly developed, it has the whole German technique around it, a lot of things were names like “leitmotif” and so on, and these became devices, which had an impact on poetry even though, people spoke, or critics spoke, very disrespectfully of Wagner’s scores. When I looked at them I said to myself, they may have looked bad to the critic, but it looked like Wagner wasn’t that bad of a poet. I wrote something for a friend of mine recently. She had a magazine going recently called Crayon, did you see that? And I wrote something, [to the effect that] there wasn’t anything why you couldn’t have leitmotifs in poetry.

Williams: You write elsewhere about repetition being important, that you shouldn’t necessarily avoid it, and that it’s actually useful for an effect.

Atkins: Well Schoenberg made such a point of avoiding repetition in his technique because, well there was a whole argument about that. Hale was one of those who constantly argued about repetition. Schoenberg’s principles … ended up kind of blurring the vision you might have had of a thing, a definite permanent thing, which I was developing as the object form. Hale didn’t like that, he thought there wasn’t any basis for that. He was more, he was too influenced by Wagner’s ideas of the melodic. Sue was saying that the melodic line was the most important thing in music but many composers of the avant-garde, composers were giving up things like that, of course Strauss wasn’t one of them, he was kind of, what his way of, I thought he was highly influenced by Wagner, this is Richard. Who else, there were so many …

Williams: I heard you sometimes went to the library and tried to translate or get things translated that weren’t available to you.

Atkins: Cleveland Library had a very good collection of things already translated so all you had to do was take the books out.

Williams: Schoenberg has writing on harmony theory, was that stuff you were reading?

Atkins: I would spend hours in the library. When I started the theory, I don’t know why I started a theory — but anyway the whole scene I was functioning wholly in the development of things. But anyway I started a theory, I put together a kind of collection of ideas I thought could be transferred into poetry. But actually it was my attempts to do that that later on became interfered with by my just growing older and somebody, people wanted the land my house was on, my aunt’s house was on, and I had that sort of thing, can pretty much disrupt your —

Williams: The anxiety.

Atkins: People sneaking around your yard, saying “oh, your gutters are not clean.” That’s how they do it, you know. If you don’t get the gutters fixed you’ll be charged twenty-five dollars. I had no money, really none, that I could afford that kind of money, so it simply put me under. Well it was whether I was going to sell or not, and my aunt had died, that all pretty much interferes with your thought but …

Williams: Well what were some of those ideas that you were trying to translate?

Atkins: Actually, people don’t know how difficult it is sometimes. Ideas are very difficult to prove that they’re yours or that they’re not yours. It is worthwhile to prove sometimes, that some ideas are not yours. I’m trying to think of all the composers I’ve worked off of, ideas … name a few extra composers.

Williams: Process of elimination! Schaeffer we already mentioned, and musique concrète. Webern, Schoenberg. I’m trying to think of more theoretically minded composers …

Atkins: Bartók. Well I haven’t mentioned Bartók. My music teacher who was still my friend at that time, I got piles of scores from her. The public library had a wonderful essay, beautiful magazine, the technical term — you’ve heard of it I’m sure, anyone who’s used the library has heard it. Journal of Psychology. They had a whole collection on the wall of the library. Started at, before the early twentieth century, they had every copy of that all the way through to around ’80, ’90. It was very convenient for anyone who was writing about how music is. So I sat in the library for days at a time, doing this. My aunt, the house belonged to her. She never bothered me about something more fundamental like getting a job, so I thought why not use that time to work on ideas.

Williams: So of those psychologists, I imagine with that resource of all those periodicals covering that breadth of time, there were many different kinds of psychologists …

Atkins: Something that referred to music, actually. Any composer who was well known could be counted on, somewhere [their] works would appear in that.

Williams: French composers we’re missing, I guess. Stravinsky.

Atkins: Stravinsky, and Satie, who I liked, but he was more the humorous aspect of music to some extent, he was certainly free enough to do the kind of things that poets were doing like using musical devices. Stravinsky was one I — in fact Stravinsky was really more important than Schoenberg, although the feeling for Schoenberg that I had which wasn’t that established was because of Hale, because he was a close friend. What was I going to say, that’s what ninety does to you.

Williams: So Stravinsky was important to you in what way?

Atkins: Stravinsky revised music in a way to cover … he did it with rhythms. Backed with strings. Absolutely irresistible. I had two and three copies of it.

Williams: Of the records?

Atkins: Records. It was easy to get this information if the subject was musical and it came up in the psychological journals and so on. They had everything. That’s more or less how that developed. The idea was that I wanted to — Schoenberg’s general idea somewhat reduced the impact of musical melody as a single line. And I didn’t like that. My music wasn’t going to be that way. So the general idea behind my theory was that I wanted to make sure that an idea, which I really began with Beethoven, actually, in which he was … well there was always a debate between why the Eroica sounded so different from a symphony by Mozart, which it does. You’re astonished. And finally it dawned on me that it was Beethoven’s handling of masses of sound, so they became like object-forms. That’s why the term developed in my mind. And something that was quite remarkable at the time. He wasn’t modern in the sense of dissonance and so on.

Williams: He had larger orchestras too, so he could muster groups of instruments to play.

Atkins: Hale could do that but I couldn’t, until some of the later ones. The books that I read on composing came to the conclusion that even composers who were well established would have to rethink passages because no matter even if you knew instrumental sounding, that doesn’t mean that you would get that exactly.

Williams: So when you hear it performed you have to go back and change it.

Atkins: I went back a lot of times. Although, well, of the pieces I wrote, I only wrote a few orchestral pieces. […] That’s an argument I had about movie music. Composers of music for the movies simply became the more modern development of some of the sounds that astonishingly Wagner had anticipated, and he referred to himself constantly that he was going to compose the music of the future. Some people didn’t agree with that. But the more I listened to his musical scores, the more I realized that that’s where he was, he actually became the music of the future. And my idea of object coming from Beethoven and then Wagner seemed to be a perfectly logical definition, but musicians are not very — they’re pretty rigid minded.

Williams: Well that skill and the discipline it takes to be a musician gives you a certain disposition.

Atkins: Amazing how all this went through my mind trying to develop some ideas about how I wanted music to sound under the theoretical, under a new … in other words everyone else at the time was searching for a new music.

Williams: Or making predictions about what that would be. One idea I had in connection to your work is actually one of Schoenberg’s. He predicts that in the future people will compose using timbres, the klangfarbenmelodie idea, color as a different organization.

Atkins: His idea of composing canceled a lot of the ideas that were already there.

Williams: Right, so he was saying other people would do this.

Atkins: In my mind melody was singular, it was horizontal. Beethoven asserted the vertical a good deal, especially in some pieces. For the time he was way ahead. Once you got the idea of music being vertical and horizontal at the same time, as a composer that’s what you were dealing with really. It turned out to be kind of like architecture, you know, and that’s before I began to build the idea of going back to the object, which Schoenberg and Hale, both of their ideas were contradicting me in a sense.

Williams: To tear down the building, to use your metaphor.

Atkins: Well I went on and then of course I got caught up … which part of the theory did you read?

Williams: You had a shorter version that was published earlier, and then you had a much longer version with some diagrams and things like that in it. So I looked at both.

Atkins: Well the whole theory is somewhere, I don’t know what in the world …

Williams: Free Lance published an extended version of it at some point.

Atkins: I would have to have had that in order to go on with the rest of it, because each part, I was analyzing the higher notes in music with the question of “were low notes really low notes, or were high notes really high notes?” Well in music actually it’s not that, it’s absolutely dominant, but at the same time, high notes can be low notes, it’s kind of an imaginative use of high and low. Like my friend who was with the Cleveland Orchestra, he played the cello, and I wrote him a cello piece, which he’d always tell me before he played it that he didn’t like it.

Williams: What didn’t he like about it? Or was he just joking?

Atkins: No, he was highly critical of music, and I don’t think he was joking. I don’t know exactly what it was but he would say that. Maybe it was the fact that he didn’t like the idea that I — a person who, and I have to admit, I had a feeling for cello performance, and so on — maybe he felt, but I think a lot of professional musicians, that’s an argument, they don’t like amateurs playing their music as well as you might think. Because it’s kind of … a pianist may play — I had several friends who played piano at the concert level — and the person who was studying music for years achieved a mental picture of themselves. They’re not that happy with people who are, even though professional — that’s why you get so much a debate in music. The Cleveland Orchestra, you’ll hear a performance of something by Richard Strauss and when there’d be an orchestra gathering you’ll hear “I can’t stand it, I can’t stand that piece.” They were actually, it was hard to get a composer, had a hard time getting professional approval by, so that I didn’t count on.

Williams: You’d composed that cello piece and he was a bit critical of it.

Atkins: I don’t think he was probably as critical of it as he wanted to make me think. Because I did a few things just from the standpoint of, I didn’t know that much about the cello, and he might have thought, “here’s someone who’s an amateur writing a cello piece and here I am a professional.” And I agreed with him on that but that didn’t stop me. Because the history of many things in music in Western, Western European music, a lot of pieces were criticized which have become the immortal pieces of the era. I remember reading: one of the critics of Chopin criticized the way he used words to —what’s the word — modulation. His modulatory ideas offended some critic, you know it wasn’t, Chopin wouldn’t fall on the right notes for that critic’s idea, which was of course the usual tonic etcetera etcetera etcetera back to the fifth and so on. But even that can be reorganized in a sense. But nevertheless that didn’t have anything to do with Chopin’s music being some of the most beautiful.

Williams: So following the expectations or the rules isn’t always the same thing as being beautiful or successful.

Atkins: They wanted you to do what they had done, follow all the rules. And a lot of music was uncomfortable when it was first written, the composer was an experimentalist.

It happened in this country where I made the mistake of not seeing more in the development of jazz. I was so impressed with Wagner and especially Tristan. Six hours of opera. Most people don’t want to listen to it. But its the first thing they tell you about Wagner, my God, they throw up their hands, “Wagner!” But Wagner’s technique was so marvelous for sustaining something for six hours. There were even arguments with European — when I would listen to the stations, European performance of operas and things, there were differences. I remember I sat once and Wagner was on for six hours, but I wasn’t bothered, I didn’t care. But some people figured that into the criticism.

Williams: When you listened to it on the radio, did you have a sense that you were missing part of the Gesamtkunstwerk, by not seeing the stage; did you visualize? Is that in a sense where part of your idea of visualizing the music was invested, because you were listening to these operas?

Atkins: Well in the case of Wagner it didn’t matter because he was visualizing for you. The rigidity of his, well the arguments about his music revolved around the fact that you are under his control. I remember one critic was saying, “how could you listen to The Ring and have to go to the bathroom?” or something like that. And some people probably wouldn’t.

Williams: There was something violent or cruel about his relationship to the audience?

Atkins: In what sense?

Williams: That you were trapped there.

Atkins: No, I’m saying the opposite. With Wagner, I don’t care how long it went, I didn’t care.

Williams: Oh, so even though you were entrapped, it was an entrapment of love.

Atkins: Even though I loved, let’s say, La Traviata, I could turn it off if I wanted to do something else, although I would say to myself: “you shouldn’t do this.” Not that I didn’t love it, but I wouldn’t have listened to Richard Strauss for that long. What’s that piece by him that goes on for an hour and a half? And Mahler, I didn’t care a whole lot for him either.

Williams: Sibelius?

Atkins: I liked Sibelius, but I thought of him as following the more or less clichéd ideas in comparison with some of the things that Schoenberg and Stravinsky were doing. Some of the later composers, like some of the music composers for [films], movie composers, they would produce some really astonishing effects for the movies. I don’t know whether they realized that they were extending. One of my favorite ones was Korngold. His scores for the movies of Errol Flynn. You could take the music out of the movie and listen to it on its own. But they stopped doing that, they didn’t think to do that ’til lately. Lately I have been wondering why they didn’t isolate some of those scores. Present them as an evening of concert music.

Williams: Copland wasn’t writing for films, but he was writing for dance.

Atkins: Yeah, Copland was a very interesting case. I must admit I didn’t care for his music. But he did do one thing, he did like Gershwin did, performed music that you did identify with America. I was listening to a movie the other night and I thought, that sounds so familiar, and it turned out when I thought of it finally it was familiar, it was that “Walking the Dog” from one of those movies with Ginger Rogers and Fred Estaire. But all of this is in the past now. Anybody who’s my age … well I don’t know if I’ll get back to the theory again, but Hale, we used to argue violently in the evenings. He wanted to know what an object form was, and I couldn’t understand why he didn’t understand what an object form was.

Williams: For you it was intuitive.

Atkins: Yeah, kind of. There’s no way not to understand it, it’s the form of an object. Why can’t you make that. A lot of music in a sense, all the way to the past, that’s the European extraction, was that, object formations in sound. And then as I said when Beethoven hit on the idea of masses of sound and the power of his orchestra at the time simply crystallized the object form for me.

Williams: Some of the ways you talk about music and this idea of the object and phenomenalism, and even the way you had of drawing diagrams in the essays you also applied in some cases to these more scientific essays. And I was wondering if you remembered composing some of those for Free Lance. I brought some of the images, just because visual similarity between these scientific essays and the music essays and I was wondering what was going on.

Atkins: Now where did you get this?

Williams: These are out of Free Lance.

Atkins: Yeah well that might be. [Reading] “Abstract of the Hypothetical Arbitrary Constant of Inhibition: Continuumization Becoming Consciousness.” Oh yeah, I remember this. I’m trying to think of what piece I had been working on at the time. But the last part is very important. “Continuumization Becoming Consciousness.” Well I took that further along. I turned that into an actual train of thought, processes that didn’t have that much to do with music. It became a philosophical idea in itself. Because in the Journal of Experimental Psychology some of the articles were on energy and mass and things like that. And I was really quite fascinated by, especially recently — where did you get this Free Lance?

Williams: The copies are held at the New York Public Library.

Atkins: Yeah, that was one of the basic principles of my, the idea of energy becoming mass. Of course an Einsteinian idea. Well that was in a sense the way that music and science combined in those days, everybody was quoting E = mc2.

[Some current events break into the conversation: the presidential election and the death of Harambe the gorilla. This is attributable to the fact that his roommate in the facility watches television all day, but also shows that Russell is very aware of the world, despite his isolation here, and continues to reflect thoughtfully on it. That said, his situation makes it difficult to write, as he acknowledges.]

Atkins: The puzzle I have now, I’m puzzled by my own, how memory works, you know, it forces itself on you. Now some of it comes back to me wholly. But I couldn’t think of it the other day when I was talking to someone, what was his name. I used to give talks, and I got caught once or twice, my ideas build up to a point, and I got to that point, and I couldn’t think of what I had put there. And there I was in front of an audience, you know. It’s very embarrassing. So that’s one reason I stopped giving talks. I wouldn’t have given up talking. I used to go out and read, give readings of poems, sometimes they were from legitimate, what’s the word I want there, classical poems, Intimations of Immortality, something like that, but I got to the point, I got to some of the lines and I couldn’t think of them for the life of me, they were just gone. And that’s still happening, and I dread the day when something worse comes along. Course I should have understood it, ’cause even when I wrote poems I couldn’t remember them from one time to another.

Williams: Well sure. You don’t have control over what sinks in and what doesn’t.

Atkins: And that’s troubling too, not having control over mine quite clearly taught me that. In fact, it’s influencing me now. People who call Hillary Clinton, “she’s untrustworthy,” and I thought to myself, who is trustworthy? I know my mind isn’t trustworthy, and the people I know, they’re not any more trustworthy than I am. It just gets more and more things … I’m wondering what I meant by them [the diagrams]. I did mean something because I have prose versions of them, or had, which, if I ever find those. Well I’m glad to see somebody, you found those in what library?

Williams: The New York Public Library. The Schwarzman building with the lions out front and everything.

Atkins: What did they say? I wonder what they think of all this. I’m awful sorry I didn’t keep a copy of all this.

Williams: Well you’re welcome to keep those. And I can send along — I haven’t copied cover to cover all the issues of Free Lance, because I was doing it by hand, but I have a lot of the stuff, so I can mail it to you.

Atkins: Well anything you think might interest me. Well maybe you shouldn’t, because I’m here. And these drawers are full, and they don’t respect your stuff here, if you put it like this, on the edge of the bed.

Williams: People admire the “Trainyard at Night” and “Trainyard by Night” poems, but this one is particularly, I like this one a lot. It is more visually striking. [Referring to “Nocturne and Prelude.”]

Atkins: I appeared in a number of, oh some twenty or something anthologies, and the one that people chose was called “Night and a Distant Church.” You have that? [Laughs.] Oh! That’s an earlier version.

Williams: People have commented on the two different versions of that poem, and I’m sure you changed, as you said, lots of the poems.

Atkins: I was probably too stupid not to hide revisions [laughs]. That’s probably what it is.

Williams: Do you remember what you were working through when you revised that one? What was unsatisfactory about it?

Atkins: It might have been … I don’t know why I lose track of everything [going through papers].

Williams: Oh, here’s the later version.

Atkins: I’ve got that one … I’m trying to find … do you know Lou Turcot, who put out that anthology?

Williams: [Reads cover] Louis Turcot. An Introduction Through Writing.

Atkins: That’s every device that poets have ever thought of.

Williams: Oh, so they included one of your poems in here as an example?

Atkins: Yeah, the one you just showed me. That anthology I believe, the one that I changed, they put the “b”s in a certain place.

Williams: Page 140. “On Sonics.” That’s the section you’re in. OK yes, I see they published a revised version of it.

Atkins: Course I didn’t approve of Shakespeare being so close.

Williams: In what sense? Unfair comparison?

Atkins: Yeah, unfair comparison, no one can compete with Shakespeare. No point in that. But I suppose that …

[I circle around again to the question that most interests me: his theory that music is written for the eye rather than for the ear, and what the implications are for sound generally, and for his poetry specifically. His answer surprises me.]

Williams: Since they included that poem in that section on sonics, and since you had this theory about music and the way sound functions in music — in a visual way — was that also organizing how you thought about sonics in poetry? So is the sound of poetry — that’s presumably also visual.

Atkins: Sometimes, yes. But ideas are peculiar things. You think they’re gonna work one moment, and then they don’t.

Williams: What’s neat about that idea is, that when it shifts the focus from sound, which is our common-sense way of thinking about music, then it suddenly shifts it to the visual. It leaves sound behind a little bit, so to speak. So then sound, it becomes this question of, what is it? Since you’re experiencing sound in some way when you’re listening to music.

Atkins: That’s a problem I didn’t try to solve. That’s how I kind of got an edge in giving readings for a short while, back the in the ’40s and ’50s: the audience would be listening to me reading in terms of sound and then suddenly, I would do something like mmmmm and they liked that.

Williams: Do you mind reading it?

Atkins: Well, problems with this: I changed it in a number of places. I decided I liked the improved version. Lou printed these final versions. Then there’s another anthology I appeared … well, I told you, I used to have a stack of early publications. Well some of them, they actually they would pay a few dollars for, you know. There are some you can buy now, like the Beloit Poetry Journal, and I’ve got the first edition. Maybe by making sixty or seventy, they might be worth something … I think I’ve talked enough. I don’t have anything more to say. There’s a lot of things I should do, but I’m not going to do them.

Williams: Are you writing now?

Atkins: No, I’m not, and that’s my big problem. Yesterday I thought I’d try a poem on the little boy and the ape, the gorilla, but I didn’t do anything with it.[7]

Williams: It was a compelling, strange moment.

Atkins: It was an odd moment […] it looked more like he was protecting the child at some points, the world of nature made it so bizarre, you do so many things you don’t intend to do. Well I hope you haven’t spent your time for nothing.

Williams: No, not at all, it’s been a real pleasure. Are you, how does your voice feel? Would you mind reading another poem?

Atkins: Well I can’t read the rain poem.

Williams: Oh no, I mean, it would be interesting to hear you attempt it.

Atkins: That one is strictly visual. Oh yeah, this is one of the earliest poems I ever wrote.

Williams: It was published a bit later I guess.

Atkins: No it was published in the ’40s. Oh, this is “Abstractive.”

Williams: What is the one you were thinking of?

Atkins: Where did you get these?

Williams: That one is from Here in The.

Atkins: My friend Bob, he did a little thing, I thought you got it from there. The poem I was thinking this was was written around ’40-something, Langston Hughes really loved that, that was one of the first poems that I had read there. [Reads.] That’s called “Abstractive” because of the kind of thing I was working with in poetry in which you didn’t mention what the thing was, you mentioned how it was structured. If you look at that door over there — I see glass, a black box, the bars — and you convert it into a shape, and you use the shape in the poem. I did a number of those, but they were hard for other people to understand.

Williams: When were you writing those?

Atkins: Back in the ’40s.

Williams: So this was written much earlier and then wasn’t published until ’76 in Here in The.

Atkins: You mean that was published in ’76. Well he was getting it from the earlier time I had written it. […] I think what more people were shocked by was my use of the apostrophe-“d.”

Williams: It does create the sense of the word as an object.

Atkins: Sometimes that’s what it is.

Williams: One name that hasn’t come up is Edgar Allan Poe. Because we haven’t talked about the plays very much. And that American Gothic sense of producing an effect seems —

Atkins: Poe was way back in my, Poe is probably one of the earliest things you discover when you’re in seventh and eighth grade. Poe, I don’t remember, I thought he was good, and the mood he sets which was probably unique for the time. Until the French poet, Baudelaire, they exchanged ideas for a while. I’d like to have seen what they said. But actually Poe’s ideas of horror were, you might say that they had more appeal for me because he was never a realist, in the stories he’d tell you someone had died of a dreadful disease but didn’t tell you what it was! It was probably something he’d made up in his mind. Now, some of the things he said in his — there is no such thing as a long poem, or something like that.

Williams: The dramas you wrote are in some sense long poems, I guess. The Corpse …

Atkins: You might say even the idea of short ones came from that. I hadn’t thought about that particularly. I think the idea of short things came to me from a more modern source, in America. Americans you know got to a point where they didn’t like the length of European —

Williams: Of Wagner, for instance.

Atkins: Yeah, well, Wagner. Then the radio came with fifteen-minute performances and plays for a half hour, and that influenced me. I thought maybe you could do that with an opera.

Williams: So it was the radio plays that —

Atkins: The whole American thing starts to shorten. I don’t know where we got that. Oh because American, people are running around in their cars and all, they can’t take the time to do things. That’s one of the things that’s kept me from writing a novel, because who reads them? I guess a lot of people do read them.

Williams: But no, you’re right. I suppose the short story is cultivated as an American genre.

Atkins: But even that’s going now. You don’t need it with television. It worries me because in a way it suggests that if you keep pushing in one direction you’re going to end up in the opposite direction. Short stories, fine, like one of my friends in the workshop, he’s writing poems. I said what do you like about it, he said, he didn’t have to explain it to anybody. He said he doesn’t care whether anyone reads his work or not. I think, well, I have had that feeling myself, but I do care! I’m too old not to care, because I feel for the time people cared. There’s no telling, the day may come when people simply don’t care about me. But I have a feeling even he is going to change his mind.

1. Scholarship on Atkins is slim, but notable exceptions include the work of Aldon Nielsen in Integral Music: Languages of African American Innovation (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2004) and the Unsung Masters publication Russell Atkins: On the Life & Work of an American Master, ed. Kevin Prufer and Michael Dumanis (Warrensburg, Missouri: Pleiades Press, 2013), which includes several essays.

2. Johari Amini, “Heretofore,” Black World/Negro Digest 18, no. 11 (September 1969): 95.

3. More recently, this problem has been articulated by Claudia Rankine in her editor’s introduction to The Racial Imaginary, as exemplified by her assertion that “transcendence is unevenly distributed and experienced.” The Racial Imaginary: Writers on Race in the Life of the Mind, ed. Claudia Rankine, Beth Loffreda, and Max King Cap (Albany, NY: Fence Books 2015), 16.

4. Kevin Prufer, editor with Michael Dumanis of Russell Atkins: On the Life & Work of an American Master (2013). For other critical sources on the work of Atkins, consult Aldon Lynn Nielsen’s Black Chant (1997) and Integral Music (2004).

5. This connection between concrete poetry and the nineteenth-century mass-cultural phenomenon of floriography, the “language of flowers” is interesting in its own right as a unique insight into literary history that I have not found elsewhere in my research, and also as an insight into the influence of nineteenth-century culture on Atkins’s intellectual formation and aesthetic sensibility.

6. He is speaking of the actress Ruth Ford, sister of Charles Henri Ford, who married Zachary Scott in the 1950s.

7. Atkins is referring to the killing of Harambe the gorilla at the Cincinnati Zoo, May 28, 2016.