PhillyTalks #9: Heather Fuller and Melanie Neilson

Editorial note: Heather Fuller is the author of three books of poetry, Startle Response (2005); Dovecote (2002); and perhaps this is a rescue fantasy (1997), and two chapbooks, Eyeshot (1999) and beggar (Situation Magazine, 1998). Melanie Neilson is the author of Natural Facts (1997), Civil Noir (1991), and Tripled Sixes/Prop and Guide (1991), in collaboration with Michael Anderson. Double Indemnity Only Twice is forthcoming in 2013 from theenk Books. The following is a transcript of Episode Nine of PhillyTalks, which took place on February 10, 1999. The complete recording, as well as a PDF of the poems discussed, is available on PennSound. The following was originally transcribed by Michael Nardone and has been edited for readability. — Katie L. Price

Kristen Gallagher: So, welcome back to Melanie and Heather. Please, just start in asking questions, or saying anything. If there is anything you guys want to say to each other to start off—about the pairing, or what your discussion has been like, or each other’s work, or any responses — it’s kind of a free-for-all, so, go!

[Laughter.]

Speaker 1: I have a question for Heather.

Fuller: Yes.

Speaker 1: Two of the poems from PhillyTalks, the first ones, either “Hear Say” or “Her Say”[1] from beggar—

Fuller: Yes.

Speaker 1: We were talking in our discussion group yesterday about how you use a lot of found, heard, overheard language. We were noticing the first poem seemed like it contained a lot more overhead stuff, and the second poem grappled with similar issues, but had less found language. You had expressed in your written email to Melanie that you had some anxiety over what you called “faux” appropriation, and I just wondered if overheard stuff is still really formative in your work. And if it isn’t, or is less, can you talk at all about how you feel about that? About how that’s changed or why it’s changed? Where it came from? What’s changed about your surroundings, anything?

Fuller: I think I find overheard language even more important. I was telling Melanie during our email conversations that often language to me seems like this common cistern—you know, where we all sort of gather around this cistern, chewing the tobacco and spitting it out into the cistern, and we’re all grabbing it and putting it back in our mouths.

[Laughter.]

That’s what we do in North Carolina, anyway. But now that I’m in the civilized world, I have to talk about the common cistern as a literary function.

Where I live is particularly busy. It’s particularly lively and polyglot. I’m always picking up language and chewing it in my mouth and spitting it out. And I think that “h r say” [pronounced “hearsay”] is a lot of, you know, chewing, spitting, right there. But in another sense it’s also something that I’m more and more interested in, and that’s the concept of sampling. I’m sure you all have heard some sampling in clubs or in jazz and such.

Speaker 2: Turntable wannabe, or something?

Fuller: There you go. So, I’m at the turntable as well as at the cistern.

Kristen Gallagher: But you had expressed some anxiety about other things. What is that?

Fuller: I wish I had an implied anxiety. I think it’s more about my feeling of wanting to be responsible. I’m not really anxious, but I am often thinking about an ethical relationship, with what you do with that language you’re chewing up. Especially since so much of that language comes from pockets of my community where people just don’t talk. They don’t talk in public. They talk in their pockets.

Speaker 3: I was curious about this sampling metaphor, because with sampling in rap music, you get historical layers — different eras of music that get sampled, sometimes purposely, as a kind of commentary. So, is there a kind of historical project in your notion of sampling, in terms of sampling as a kind of recovery? Or is that not something you’re thinking about?

Fuller: Well, now I’m thinking about it, for sure.

Neilson: Can I say something? When I think about how that would apply to how I think about it, I think of it as defiance, and power. You know, breaking rules.

Speaker 3: It’s taking things out of context, I gather.

Neilson: It’s just all fair game. It’s all in selection. A poetic documentary tradition.

Gallagher: Does it matter where you’re getting it from, though? You know, because I think Heather is talking about the feeling of responsibility for small, isolated pockets of people, and you might be talking about historical —

Neilson: Yes, I think it’s probably different.

Sky’s the limit is what comes to my mind.

Fuller: Yeah, I mean, they all cross over.

Louis Cabri: I wonder if it ever causes some mania, unexpected or difficult tension. I’m thinking particularly of the moment where Ben Jonson comes up [indiscernible]. It caught my eyes, you know, as a really enigmatic thing. The reason it strikes me is because Jonson, you know, he really built his entire career by posing himself completely against what PhillyTalks, I guess, is a version of. He killed fellow actors, utterly [inaudible] violence, refusal to cooperate. And the poem that comes up here is the one in which he announces that he’s leaving the public stage. He’s no longer going to write for the theater and he is going to write solely for the court. So, I guess why that might be awkward is because he was so incredibly successful at it. He’s someone whose works are utterably invaluable and I can’t really imagine that period without them. And yet they come from this poetic model that is not very easily assimilated.

Bob Perelman: So, does that make T. S. Eliot look like Walt Whitman?

[Laughter.]

Neilson: That’s fascinating. Fascinating ricochet.

Cabri: Do you have any comment on that?

Neilson: I might. I’m thinking about it. That’s very interesting.

Perelman: Well, what about that sense of the court and the public under them? I’m sort of ruminating — it’s not going to end up being a crisp question. Heather, I was thinking about what you were saying about the pockets of language where you get the words from, and your own feeling that perhaps bringing them into a poem is bringing them into a more public space than that language normally exists in. On the other hand, I kept feeling, this conception that kept half-forming as I was listening to your work: what is the relation of the art world that you are writing in to the life world that you are writing of? The art world just strikes me now as a little analogous to the court — Ben Jonson’s court — that you are writing for. I’m just trying to sketch out some configurations and wondered what you or Melanie would say about it. I mean, it’s the big issue for all of us —

Fuller: Right.

Perelman: Anybody who wants to bring in the world, well does the world want us to use it in that way, or does it care, et cetera et cetera? These questions.

Neilson: When you say “world” though, my question is, okay, we’re talking university, society. And for me, of course, it’s society/university. Who am I writing to and for?

You know, “world” — I’m curious what that means to you.

But I think you were going in an interesting direction with this: the people who are in those pockets speaking. And then Heather does make a lot of really —more than a lot of writers that I know of writing right now —references to, gutsy artists like Claes Oldenberg. You know, a lot of people don’t do that right now, and Heather does that to visual arts. What’s going on there? How do those two worlds connect and collide or overlap? I don’t know if that’s an issue for me. I’m not sure it is.

Fuller: The really intriguing thing to me about Oldenberg is he was such a public figure. Everything for him was so hyperbolic. His sculpture was sort of upon you before you were even close to it. In a sense, he was really holding court in a very public way with whoever was in eyeshot. It’s often funny to me to think of Oldenberg in relation to, say, the person who is going to be uttering the line in “h r say” about the splatter guards from the civil disobedience unit of the police. To what extent is the splatter guard holding court? To what extent is Claes Oldenberg forcing court upon us? These are all very public and visual elements that sort of force themselves into our space. And so often there’s a disconnect between these very forceful and — you used the word “power” — powerful elements and people who will perhaps not be reading this text.

Gallagher: Following up on this idea, I was reading “h r say,” or I wasn’t reading…I was having a lot of trouble reading “h r say,” and so I am wondering what it means to take this spoken language, this overheard language, and then to actually write it down. Because that’s different than the cistern where you pick something up and spit it back out in the same form. In some ways, if you’re taking language you are overhearing — for me at least — in this poem you’re representing it in ways that I couldn’t re-speak. I could read it; I could look at it and make sense of what the words were and sense these absences, but I wasn’t sure how to re-speak it. I don’t know what that is: if it’s trapping it on the page, or if it’s reclaiming in a way that doesn’t put it back in the cistern in the same way. I don’t know.

Fuller: Well, that’s the whole sampling idea I was getting at: spinning it back out in a sample pattern.

Perelman: So, just in a common sense way, that’s the missing vowels.

Fuller: Right, as well as the reconfigurations of the spoken word, when things are repeated throughout in different configurations.

Speaker 4: I’d like to hear you talk some about placards, because to me it seems like those bring up some of these issues. I mean, the whole idea of appropriating something visual, something that does hold court in the sense that you are talking about. Then what does that mean to imagine that visual idea, but then have it not hold court in the same way, have it be in a book.

Fuller: And that’s sort of my plea at the beginning, you know: “Please take one up. Photo enlarge at will.” Yeah, they are just very simple text boxes that have sort of been placed in the context of being something larger than they are.

Speaker 5: Don’t you have that line: “how do we recover from the book”?

Fuller: Yeah, which is an anthology.

Neilson: It’s interesting to me. When I saw, experienced and read those, what I thought was so powerful, beyond just how they were laid out, was your direction — the graphic, the visual, the text in the book. You transformed everything by the direction that goes with them. In the way that, you know, when you’re reading … I was reading The Mother by Brecht a few months ago. It’s like that one line of direction. What you want us to do with them is so powerful. And it’s funny, those words just hang in the air. Then when I see them in the boxes it’s powerful, but my mind really runs with the direction you’ve given: what you want us to do, the agitprop, sort of, adds complex ideas to the dramatic event of reading.

Fuller: The whole idea of imperatives in poetry is increasingly interesting. Being told what to do by poets. The second person. Poems being written just in second person.

Gallagher: Well, back to the art and life idea, I was just thinking of Debord and that “beggar” in the first stanza. You talk about pockets “full of mutter,” and then “the museum is a cadaver of curious facts.” Do you guys have a Mütter Museum in DC?

Fuller: A mutter museum?

Perelman: Mütter. Mütter Museum.

Gallagher: I thought there was one down there. It’s like a museum of medical mishaps.

Perelman: That’s here.

Gallagher: I know. I know.

Fuller: We have one at Walter Reed Naval Hospital. It’s an army hospital.

Gallagher: Was that sort of what you were playing off?

Fuller: I would like to say that, but no. It’s quite literally mutter. But that museum is quite fascinating.

Gallagher: You should say that’s what you meant.

[Laughter.]

Neilson: She should be your agent!

Gallagher: It works so well with those lines. I don’t know, maybe it doesn’t matter. Just this idea of the way that you might look at something in a museum and the way you would look at someone on the street who is homeless and propped on a crutch. And how it’s okay, in the Mütter Museum, to just look at those things, and be sort of horrified and fascinated. It’s a sort of art because it is in a museum. It’s like a framing. And then things that we are afraid to look at or deal with are standing right outside the museum.

Neilson: I’m still thinking about Ben.

Cabri: Let me throw another one at you.

Neilson: Bring it on, bring it on, baby.

Cabri: This is from the very beginning of “Moxy where its mouth is” and you have this line “any anarchy is surprise and language is a surprising tool,” and then immediately after that, “where readers come into and how is a seesaw or seizure dialectics of self and other.”

I would like to ask you about what I see as a very strong opposition between anarchy and a notion of … and maybe this is implied by the language in a cistern, in which language is this kind of royally infinite, infinitely proliferating —

Cabri: Mess.

Ben: Mess.

Neilson: Mess.

Cabri: Whereas dialect —

Neilson: Mess. For me, that’s true. Yes, life-affirming language activity.

Cabri: Whereas dialect immediately restricts that, it says there is a certain logical relationship that precedes language, which determines its content, and, in that sense, language has all of these formal restraints on it that you actually can’t mush together easily at all. It really resists being boiled together because of syntax and grammar and things like that. So, how do you traverse that tension, if at all?

Neilson: How do I traverse those wild waves of conflict and contradiction?

Cabri: Yeah, well is it conflict or maybe [inaudible]?

Neilson: I think maybe both. It seems like that yin and yang sort of thing. They can coexist. Maybe there’s a way they don’t really cancel out each other really? Do they?

Cabri: To me they do.

Neilson: I understand. I think it is provocative. You’re talking about, you know … We have over here our graphs, our plaids, the dialectics, our system, and we have over here montage for a working method, whatever.

I don’t know. For me the cistern and the chewing tobacco is not really something … taking it out and putting it back in again, it never occurred to me. And the sampling also is something I have to kind of think about. I’m not really sure how I can say that so neatly for myself. My ways are my ways.

Speaker 6: Maybe one way to think about it is just in your terms of reading Heather’s work, that although the cistern is Heather’s metaphor and we’re talking about it as a kind of chaotic —

Neilson: Communal.

Speaker 6: Communal thing.

Neilson: Juicy. Communal as the sound of traffic, as the words drive themselves free to roam. Who owns the words?

Speaker 6: It seems like in a way, I’m just thinking of this line from “Fuller’s Law,” where you say, “skeptical of rejecting sentiment / narrative.”

Neilson: Right.

Speaker 6: That struck me as one of the clearer moments of straight commentary in terms of Heather’s work vis-à-vis the work of her contemporaries, or whatever.

Neilson: Right.

Speaker 6: So, in that sense, I’m wondering whether that can be squared with this metaphor of the cistern, or whether it needs to. So, how are you reading Heather’s work, I guess I’m asking, as sceptical of rejecting narrative in particular?

Neilson: Well, that’s a good question. I think as self-aware and site-specific work and not purist.

Speaker 6: And what are the motives for not rejecting narrative?

Neilson: You’d have to ask someone else. I don’t think I can answer that. But I find it fascinating in Heather’s work that she gets away with some things, or she is pointing to some things that other people that I read with pleasure and excitement don’t do. What I mean is that she is pointing to — when she was talking about the pockets — I thought that was an interesting way to talk about it, lifting or sampling from overheard wordage. I’m struck by the, if it’s only two words, and then I find two more later, and they point back to each other, and I am experiencing a cumulative effect, dramatic or emotional, that’s when I come to sentiment. Something is taking place, and I think we can say the word “content” in this room without people starting to crawl out the windows. It’s tricky because she’s doing a lot of complicated things. I had never really read closely Heather’s work until the past year, ’98.

Speaker 6: So, when you’re reading, those things get narrativized? You can see words that come up or echo each other and all those things —

Neilson: I think narrativized is a bit of a clumsy term, but I appreciate that you’re trying to put some kind of label on it. I love the activity of the sound of her work. I don’t need it to talk narratively to me.

Speaker 6: So, they recall a sense of place or a theme or —

Neilson: I guess what I would say, I really meant it when I said the word rejecting. I think that there is something not pure about what she is doing.

Cabri: That’s evident from the first two poems in the newsletter that are very narrative. [Inaudible] “beggars can’t be choosers.” There’s a circle that closes or draws, goes back to the point where it begins from, once one has come to the end of the poem “beggar.”

But I’m just thinking about this, the idea of a common cistern, and then your worries about in some way stealing from it, I guess.

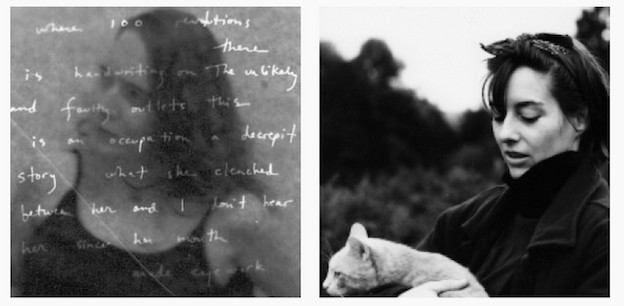

Melanie Neilson, with Spock, Kirk, and McCoy. Washington, DC, 1999.

Fuller: I’m not worried.

Cabri: But yet, it’s a common cistern.

Fuller: I’m not worried.

Cabri: [Inaudibe] scare quotes around some stuff you’re taking as if it has in some sense a form, it’s formed before you take it.

Fuller: Right.

Cabri: You are in some sense re-forming it, or just forming it, which kind of suggests to me, Melanie, what you have done in some of your work, both in Civil Noir and in your last book, I forget the exact title — Disfigured Texts?

Fuller: Yes.

Cabri: If the subject that we are talking about is “where does one’s language come from,” then for you it seems like the idea of language is as a common pool of static voices, et cetera. The metaphor there, for you, seems to be a sense of layerings of text, right? So, in your Disfigured Texts, you have typed texts and then writing scrawled in between the lines of type, and then there’s that sort of visualized — much like a placard or like a scrap of paper — and then that’s put aside, put next to an actual version, in some sense, of that rewriting.

Neilson: A transcription. Mapping word events. Manipulated, misquoted and remixed is the process and a study.

Cabri: A transcription as a poem. But it’s called Disfigured Texts, so that the process is not from preformed to reformed text, but it’s from disfigured text to disfigured text.

Neilson: I’m with you, yeah.

Cabri: I don’t know if I am with myself.

[Laughter.]

Neilson: You can do whatever you want and say, but can you really?

I’m completely disloyal, and I steal. It is an activity to alter a new work, crossing pieces of text with pieces of text. And often, it’s scrambled signals. It’s actually very mundane.

Speaker 6: The one place where it makes me nervous, and I am talking about my own writing practice here — not nervous upon reading your work — is when that kind of stealing marks itself aggressively as appropriation, or if I feel like it does. So that then you’re not just taking the common language, you’re taking a particular person’s kind of language, and using it. Then the question of motives comes up, and rights, I suppose. Those sorts of questions. That’s the place where I get anxious myself, and I have to start wondering about why I am doing things, and what happens when I do them, and all of that.

Fuller: So, when you say a particular person’s kind of language —

Speaker 6: Well, vernacular, in the vernacular. Taking vernacular speech from working-class Portuguese people in Providence, Rhode Island: that makes me nervous.

Neilson: What about if you wanted to borrow some language from the Disney Company’s service-worker’s manual, that kind of language? How would you feel about that?

Speaker 6: Better.

[Laughter.]

I don’t know why, I feel like I would be —

Neilson: They’re very different, I think.

Speaker 6: Well, one is institutional.

Neilson: Your feelings are different about it.

Perelman: Yeah, well, it’s critique or it’s empathy, and those are —

Speaker 6: Exploitation.

Perelman: Yeah, exploitative.

Speaker 6: I feel like I have to be very careful about tone and all those sorts of things.

Speaker 7: There’s actually some words here that seem a little nervous, more nervous, Heather, than you’re letting on, and I wonder if I’m misreading them: “I think the specific poet moves beyond your act of witnessing,” [Actual text reads, “I think the civic poet moves beyond the mere act of witnessing.”] begins to ask questions of your responsibility. So, there is here this play, it’s actually a simple tactic: witnessing and interrogating. And testimony is what shows up, you have testimony. There is sort of this language, the law of guilt and responsibility, which at least is latent.

Neilson: Well, I think if I recall, that was from one email that was actually titled Civics 101. Heather actually sent me something called Civics 101.

Speaker 7: It’s about the citizen poet, the comrade poet.

Neilson: And you mentioned you worked for lawyers, so you had a legal orientation.

Speaker 7: I was thinking of it just because of the “Three Urban Legends” poem. It seems to me that you very deftly navigate all of those pitfalls in that poem. So, that’s what interests me just in terms of craft: how do you navigate all of these pitfalls if you decide that you’re going to engage with various kinds of American vernacular?

Fuller: Well, know them well. I guess I’m incredibly fortunate to be pretty immersed. I don’t know how I would do it if I was not.

Speaker 8: Well, we were talking about this yesterday and I was bringing up questions like responsibility, because we were looking at the same passage, and we were looking at juxtaposing “bird man,” which seemed more overheard, with “beggar,” which seemed to have more of the character of the poet in it. But now at this point, I would argue, that the opposite of taking this language is simply not using it, ignoring it. So, then what?

Fuller: Right. Exactly.

Gallagher: Yeah, I think that is what I find fascinating. I mean, what I hear people saying sounds maybe more critical, but I think one of the latent questions is actually: how do you enact responsibility? That’s something that you seem to pull off in a really decent way that’s curious. I don’t know, I think I’ve lost my thread.

Fuller: No, I hear you. I think about that all the time, and I wonder if it’s just my general disdain for stories, you know. For hearing, writing, reading stories and not wanting to write stories. And not wanting to make fairy tales or myths.

Perelman: Do you read Reznikoff?

Fuller: Yes. Yes, indeed.

Perelman: I’ve been thinking about him lately. He tells stories all the time —

Fuller: Yeah.

Perelman: And it’s really crucial, you know, where the parents came from, where the kids are going, and the world doesn’t make sense and they’re not fully responsible without those stories. They’re not hokily Disneyed into a conclusion, but they’re crucial to making any of that manifest.

I just wonder about your very strong distaste for stories. And Melanie, you were saying oh gosh, can I even say the word in this room. Well, not quite, but to me all of those, it seems to me I’d like to propose a distinction, and I would like it to be, you know, the whole world to take it up —

[Laughter.]

But I think a lot of writers since Olson and the fifties have been hobbled by a kind of chimera of breakthrough, where story is one of the things we have to shoot down to get in one of the fast jet planes, or whatever. And it seems to me that Reznikoff is useful to think about narrative as a constituent part of the expertise that you have, with hearing language that you sort of know the trajectories of, the references and their sentences. You know where the day starts and where it goes in the middle, et cetera. Without that kind of knowledge, we don’t know much. The sad thing is it becomes incredibly irresponsible without that knowledge.

[Inaudible.]

Fuller: Reznikoff, like Oppen and like Scalapino, have managed to tell stories without mythology. And when I think of story in the sense of what I’m talking about, I’m thinking of the mythologized story, the fairy story —

Perelman: And yet you don’t mean myth as in Aeolian myth?

Fuller: No.

Perelman: So, ideological masking?

Fuller: Yes, exactly.

Speaker 8: There’s a kind of, I’m thinking about the stuff Carla Harryman does, which is sort of fairy tale-ish, but it’s crazy. She has this thing with these people without mouths who just keep asking — somehow, even though they don’t have mouths — “Is Darth Vader our mom?”

[Laughter.]

That seems to me very appealing —

Fuller: Yeah. That’s great.

Speaker 8: And it is a kind of storytelling.

Fuller: And she’s able to really slip around with syntax.

Speaker 8: She has this line that always sticks in my head, in this story called “In the Mode Of,” where she says, “this is not logic, but a language of logic used to other ends,” which seems very much wrapped up in her project and maybe a different way to think about mythmaking, storytelling.

Fuller: Right.

Speaker 9: I’m interested in asking Heather about the way in which the scene in the poems we were actually just looking through, the poems you read in this book, how is it that you bring issues of sexuality into this public space that you’ve been talking about? I am interested in how you do that. I’m interested to find out whether you study models for doing that, or whether it’s something that you —

Fuller: Well, sex is public space. “Try sex!,” “Fun!,” you know.

Neilson: Didn’t I read somewhere that you were the post-Language Eileen Myles?

Fuller: Yeah, that’s what Tom Devaney said.

[Laughter.]

Speaker 9: So, sex is public space, meaning that it’s being excelled?

Fuller: Well, you know, the boys on the street corner yelling “pussy” out of context. The car window issuing “freak” to the fabulous drag queen. It’s less a personal sense of sex than it is a sense of witnessing it. And asking a few questions about it.

Speaker 9: Witnessing the situation of the language?

Fuller: The language around perhaps what’s seen as deviant sex.

But I don’t think of any models really. I don’t know that there is really unified sex in my work. It’s more about what is present in the landscape of the language that is at work in a poem.

Neilson: I perceive that there were some gender identities in the landscape. These things, you know, you mentioned these shards of that spectacle.

Fuller: Right, right.

Then there’s “the American cock and the American hen back together again.”

Perelman: I detect a little mythology there.

[Laughter.]

Neilson: Grammars, then primers were sources for systems, like homilies, I was looking at those.

Speaker 9: I have a question about the footnotes, which maybe is a restatement of my question about anarchy —

Neilson: That’s fine.

Speaker 9: So we have in one sense a schema going here of a kind of communal, royally cisternal language in some sort of dialectic where the self confronts an other, and their primary relationship is one of negation and antagonism. It interested me that after this kind of collaborative wealth of material, that I got a very careful adumbration of whose was what’s, and how the final bid — “all else, my language” — tipped it more to the sort of dialectic side. So, I wonder if this gives you more of an in than maybe [inaudible].

Neilson: Well, it’s interesting that you bring this up because I added more to the notes. So, I actually have more here than ended up in the piece.

I think the element of fun and play and nonsense too, is important to me. And so, when I say “all else, mine, me, mine, mine mine mine” it’s very single minded.

It’s play. And, you know, if it’s coming across to you as particularly you, reader, then it’s having too much of my cake and eating it too.

[Laughter.]

I mean, in all seriousness, maybe that’s too easy and not fair for, at least for discussion.

Speaker: Well, it does seem that there are lots of motives, interesting motives for that kind of play in these poems, though, particularly around issues of readerly choice. This line, which —

[Indiscernible.]

Neilson: Completely ignore some of it, then add something that wasn’t there, then later on think, “well, you know what, I’m going to revise that,” or maybe you don’t. I don’t think we have too much time for autobiography here tonight, but as an undergraduate I was told about one of the professors, David Antin, who performed “talk poems” and I said, “oh, really?” He was an inspiration to me.

[Laughter.]

And he did, he just got up there and talked. And it’s always been something that I took with me. I loved that he just could change direction at will, mid-performance. When I don’t read frequently I often do that too. I see something I don’t like or don’t remember and I will change it, or I stumble. And I also stumble when I am actually putting in text, or change when writing. It’s interesting, just the performing of it, the making of it, and then round and round we go.

One thing I did want to mention is that Moxie, the soft drink from the 1930’s, was one of the things I added in my notes. It seemed important.

Perelman: Which came first, the soft drink or the —

Neilson: Some people say the soft drink came first. The effervescence that gives you the courage to be so, I don’t know. Or perhaps it takes moxie to drink Moxie.

Perelman: The new taste of Dr. Pepper.

I just wanted to ask, this might be a [inaudible] question, but about the performance, do you ever, I mean, you must feel a kind of weird, like I feel when I look at the page and you see “O poet of fortune!” And you don’t, one couldn’t — statistically you just couldn’t generate the way you read it. It’s like the monkeys typing King Lear. Well, a million readers reading that line and looking couldn’t create the tone of voice that you use. So, it’s just a big problem —

Neilson: It is.

Perelman: It’s the page versus the CD, or something. I don’t know, do you want to go CD instead of page sometimes?

Neilson: You know, when I was listening to Jack Spicer reading The Imaginary Elegies for the first time, it was so shocking to me. I felt so incredibly sad, because I’ve read him over the years with different ideas about it, but that was not there. I go and look at my Black Sparrow, beat-up collected this and that, there’s a great distance there.

But then, what are we doing, this is poetry? This is not show biz, and the fact is the small room of people so lovingly gathered or maybe some very obligated, I don’t know. And tonight, god forbid, this is going to happen again, but I had a very particular reading tonight, and I guess it’s the nature of what we’re doing, what some of us are doing.

Hey, if anyone wants to record it and put it on a CD, I’d love to be part of it. Like you said, there’s a sadness. How do you deliver?

Speaker: There are poets who completely destroy their work for an audience sometimes. It can go the other way, but there are people I’ve heard once and I can’t read their stuff anymore because there’s this horrible, grating voice reading those lines. So there are some people who really need to stay on the page, I think.

Speaker: Well, isn’t that what you were saying about Spicer, that it was disappointing?

Neilson: No, it was magnificent to hear his voice! I was so sad because I had read and missed his presence, had never heard his voice, and the lightness, it was so lovely.

But then, you know, who am I fooling? It’s mortality. It’s like, come on, oh, he’s gone. So are a lot of people, and they’re gone. You hold on to something and it just brings up something that I think everyone has feelings about.

Speaker 10: But I think you bring out, I mean, reading, it works differently for everybody. You play with tone so much in your work, and as Bob said, it’s hard to read that on a page at first go. But, I would think after you’ve immersed yourself in that, and read enough to get an idea of what it is you’re trying to get at, you would be better capture, not captured, but —

Speaker: Now, you don’t do too much graphically to try to represent your voice. Given all of the different inflections, that’s interesting.

You know, I mean, I think that’s always a problem —

Neilson: I mean, it’s one way. One way to perform it, and someone else could perform the text another way, something of the sort that Charles Bernstein was saying in the introduction to the book, The Performed Word?, that there were different ways, different performance styles —

Perelman: Close Listening.

Neilson: Yeah, right, that there are different ways to read and have things read.

Fuller: And one would hope that a reader would spend time with a text. I mean, “Turntable Wannabe,” it demands that you get into the piece. “Sleeping Bag USA,” “Civil Noir,” you would hope that you can get into the piece and spend time with it, so that when you reach “O poet of fortune!” you will have gotten into the rhythm.

Neilson: Or not.

Speaker: So, in a way Melanie, you’re thinking of yourself, at least when you are performing things, as just another reader of your own work?

Neilson: Not just another.

[Laughter.]

Speaker: A special one, but nonetheless.

Neilson: It’s okay, it’s a good question to ask. I’m the one who put out the stuff, so to speak.

Perelman: You’ve spent the most time with the writer. You really know her well.

[Laughter.]

Fuller: Absolutely.

Jena Osman: I have a question about performance for Heather. With you placard poem, the last poem you did with Mike’s voice, it seems that your poems are moving somewhere off the page, and I’m wondering if you’ve done work like that, or if it’s a direction that you see your work going into.

Fuller: Yeah, I’ve done a lot more work like that. The placard form has, sort of, leapt into another form all together that’s sort of linked to the Internet. So, I am always intrigued by how text does leap off. And I do want to get audiences more involved in producing text.

Osman: So, you’re using the Internet for that, or are you using actual performance?

Fuller: I’m using actual performance. I’m actually rigging the audience.

Osman: In the way you did tonight with having voices coming from the audience?

Fuller: Different ways, different ways. You should come to DC on April 22nd, because I’m doing a new piece that is completely audience-driven.

Speaker: Where is that going to be?

Fuller: I’ll give you info.

Gallagher: Well, everybody got their questions asked? Thank you.