'Dancing in a straitjacket'

An interview with Ron Padgett

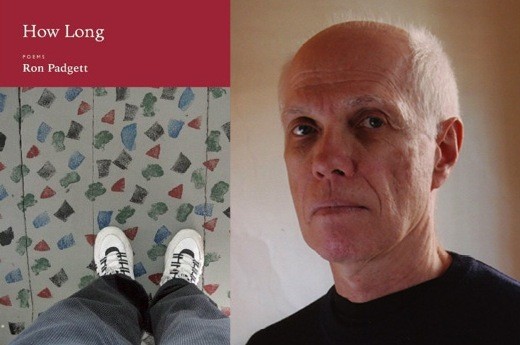

Editorial note: Ron Padgett is an American poet, editor, translator, and educator. He edited The White Dove Review with Dick Gallup and Joe Brainard from 1958 to 1960, directed the St. Mark’s Poetry Project from 1978 to 1980, and then took a position as publications director at Teachers and Writers Collaborative, where he edited and wrote books about teaching imaginative writing to children. He is the author of several books of poetry, including Great Balls of Fire (1969), The Big Something (1990), and How Long (2011). He has also translated Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp by Pierre Cabanne, The Poet Assassinated and Other Stories by Guillaume Apollinaire, and Flash Cards by Yu Jian. His Collected Poems is forthcoming from Coffee House Press in the fall of 2013. Yasmine Shamma is currently a lecturer in English at Oxford University, where she teaches courses on twentieth- and twenty-first-century poetry. Her work has appeared in PN Review, Essays in Criticism, and Jacket. She is currently writing a book on second-generation New York School poetry. This interview was conducted and recorded on April 11, 2011, in Di Robertis pastry shop in New York City. Yasmine Shamma subsequently transcribed the interview. — Katie L. Price

Yasmine Shamma: Diving into An Anthology of New York Poets, I was rereading the introduction, and noting that it was written in 1970 —

Ron Padgett: I was a child when I wrote that with David Shapiro, who was even more of a child.

Shamma: But you did say something that people have been saying ever since then: that the term “The New York School” isn’t helpful, and that it doesn’t do as a generalization or an abstraction. I was wondering if you still feel that way.

Padgett: Yes, but I’m tired of telling people that. They keep using the term, and by now there have been a lot of disclaimers. When John Ashbery gets asked, he says pretty much the same thing. Other people do too. I don’t have much use for the term. I’m not a critic or an essayist, so I don’t need to use it.

Shamma: Do you think that there are definitive characteristics of the people who wrote in New York in the 1970s and ’80s?

Padgett: You’ll have to tell me which poets. Otherwise I won’t know what I’m generalizing about.

Shamma: Ted Berrigan, Edwin Denby —

Padgett: You couldn’t find two people more …

Shamma: I know! Okay, James Schuyler, etc. Basically I’m thinking of the post-Frank O’Hara and Kenneth Koch wave.

Padgett: Except Edwin [Denby] was a pre-O’Hara wave, really. Are you trying to point to people who came after Frank?

Shamma: I guess I’m trying to point to the group of people published in C, the magazine edited by Berrigan.

Padgett: Even there you’ll find quite a variety of people, from F. T. Prince to Harry Fainlight. Ted’s editorial policy was stated on the copyright page, something like: “C will print anything the editor likes,” which is a pretty good editorial statement. And Ted liked a lot of different things.

Shamma: I guess I’m talking about people who were illustrated by Joe Brainard?

Padgett: When you look at this anthology, you find people as diverse as Clark Coolidge and Edwin Denby, Tom Veitch, Ed Sanders. That’s why we didn’t call it a school — just An Anthology of New York Poets. It included people whose work we liked, sort of like Ted’s policy. We knew or had met everyone in the book, except Clark Coolidge. Most of the poets in that book … well, let’s just talk about John, Jimmy, Frank, and Kenneth. All four of them were (and John is still alive, of course) very smart people, very well read, sophisticated in their thinking, witty, and they had pretty high standards. They were interested in different kinds of art — dance, visual art, music — and three of the four were gay. They were all white males, and three of those four were Harvard graduates.

Shamma: Very different, I guess, from the subsequent sort of group — I mean, I know you went to Columbia.

Padgett: Yes, how awful!

Shamma: Well, in the introduction to Kenneth Koch’s Selected, you mention being taught by Kenneth, and that he taught you how to be witty?

Padgett: He didn’t teach me how to be witty; he gave me permission to be witty.

Shamma: I guess that feeling of permission gets passed on through the generations as a marker?

Padgett: As many things do.

Shamma: It seems that most of the subsequent poets were somewhat more self-taught —

Padgett: I don’t know about that. Ted Berrigan had a Masters degree in English; Tom Veitch did a year or so at Columbia; Tom Clark had an MA in Poetry from Michigan, won the Hopwood award, and also did graduate work at Cambridge and the University of Essex in England; David Shapiro got a PhD … I could go on and on. There aren’t many self-educated people in the anthology. Whether you’re educated by yourself or by somebody else, or a combination — I don’t really make a distinction. But going to Harvard confers a kind of distinction on you. It was the first and is the oldest university in the United States; it has a great reputation, the largest endowment. So being a “Harvard man” has a kind of ring to it, like being a “Princeton man.” Whereas if you graduated from Podunk University, you go out into professional life with one strike against you. Of course, all the people in the anthology were in poetry, so higher education credentials didn’t make all that much difference. To me, none.

Shamma: Right. Well, I guess the reason that I’m trying to make a distinction about education is because immediately, it’s clear — in your case, reading this kind of poetry — how everyday, or conversational the poetry is.

Padgett: The so-called second-generation New York School had more of the conversational element in it. Back in those days, John’s poetry didn’t have a lot of it. Frank’s did though, and there was a kind of conversational poetry that came from Williams through Frank, and people like Ted and me and others picked up on that. Another distinction between the earlier guys and us was that they were of a generation that liked alcohol. My generation wasn’t that much into drinking. We were more into smoking pot or whatever else people did.

Shamma: Why do you think that was?

Padgett: For me, smoking pot was a lot more fun than drinking. Heavy drinking made me feel awful. I’ve been drunk twice in my life, and I hated it both times.

Shamma: That might be a record for poets!

Padgett: I had a lot of fun smoking pot. Pot had become much more available. When I was growing up in Oklahoma, it was virtually impossible to find.

Shamma: And then you come to New York City in the sixties —

Padgett: It was easier in New York. Especially after I came back from living in France, after 1966. Everybody was smoking dope like crazy.

Shamma: So was Great Balls of Fire written in France?

Padgett: The earliest poem in that book was written in 1963 in New York, when I was a junior at Columbia. The book came out in 1969. I guess the latest poem in the book was written around 1967. So some of them were written in France, yes.

Shamma: And did you see a change in your work after going to Paris?

Padgett: I guess it did change, but I’ve never thought about it much. In Paris I was reading a lot of poetry in French, and I was speaking French, and immersed in French, so I had the resonance of that language in my head. It kind of got confused with English. In fact, by the end of my stay in France I was so used to speaking French that sometimes I would try to say something in English and all of a sudden I couldn’t quite remember how to do it. It was a strange experience.

Shamma: Yes, I can imagine how that happens.

Padgett: Anyway, I’m not good at analyzing my own work.

Shamma: Have you read any analyses of your work?

Padgett: Yes.

Shamma: Have you found them to be true?

Padgett: Every once in awhile somebody writes something that strikes me as smart and true and perceptive.

Shamma: Are there any critics of the New York School that you think are particularly on to it?

Padgett: There are a number of people who have written things about the so-called New York School that have been intelligent and apt, but I don’t think anyone’s ever told me anything that I didn’t already know.

Shamma: It’s all been pretty obvious?

Padgett: To me, yes. But some poets are much harder to write about than others. Some are elusive. It’s hard to get in prose descriptions exactly of what’s going on. Others are easy. My work is hard to write about.

Shamma: Yes, it is.

Padgett: And that’s neither here nor there. But a couple of people have, in recent years, written some things that have struck me as pretty sharp. For a long time, all anybody could say about my work was, “Oh, he writes a lot of different kinds of poems, and he’s funny.” The first thing is true, and the second is only occasionally true.

Shamma: Yes, I was actually going to say that I don’t think that second thing is true.

Padgett: I remember some critic taking me to task by saying, “Padgett’s very funny and jokey, but why doesn’t he write about something serious, like death?” It was such a wrong-headed way of seeing things, and also inaccurate. So I sent the guy a list of the poems I had written about death and published in my books, but I never heard from him.

Shamma: I can’t believe you didn’t hear from him!

Padgett: Well, anybody who’s stupid enough to say the first thing is stupid enough not to answer. I wasn’t arguing with him; I was giving him empirical evidence: here are the books you claim I’m being funny in, look at all the poems that are about death.

Shamma: This is me going out on a limb, but I find that you and some of your peers write with such — maybe this is me being naive — but you write with such honesty that it becomes really difficult to talk about anything, because it’s just there. It’s this sort of half-showing that you don’t expect. I mean, I don’t see how you could come to this kind of page and be closed as a reader. And so, turning to criticism and academic stuff, it becomes really difficult to say anything seemingly worth saying.

Padgett: I see what you’re saying, I think. Two things come to mind. One is that, in the work of a number of poets of my age and before, openness was a characteristic that I admired, and I still do. It doesn’t mean you’re going to write a good poem just because you’re open. You could be spilling your guts or confessing to something horrible that I might rather not know about. But on the other hand, without openness toward oneself, I think it can be difficult for poets to figure out what to do next in a poem, and to figure out who they are even. The other thing I wanted to say was that, in fact, I have a poem called “The Coat Hanger,” in which I talk about this very subject. It’s in a new book of mine.

Shamma: Is that the one that’s being published right now, in April?

Padgett: Yes, and I think I might read that poem tomorrow night at The Poetry Project. Anyway, if you check the poem you’ll see some of the things I say there, and the people I quote. What’s the other thing I wanted to say?

Shamma: About openness?

Padgett: Oh dear, at a certain age, the brain cells crust over. The other thing I was going to say was more interesting than that, to me anyway. What did you say before that?

Shamma: Well, I was going to say, in terms of Frank O’Hara mainly, as a poet who says he wants his poems to be “open” and his face to be “shaven” —

Padgett: Yes, “You can’t plan on the heart, but the better part of it, my poetry, is open,” that’s what I quote in “The Coat Hanger.” And you said something about the difficulty of writing about that kind of poetry.

Shamma: Yes, the incredible difficulty.

Padgett: It’s particularly difficult to write about the obvious. Let’s just say somebody writes a poem that says, “I’m in love!” What are you going to say, as a critic?

Shamma: You say, “look at how you spread those words out in one of your poems and talk about” —

Padgett: I do?

Shamma: Yes, I have [it] here with me, actually …

Padgett: Oh, you’re talking about the poem in Crazy Compositions.

Shamma: Yes: “I Love // each word increases squared”

Padgett: Isn’t there a “you” anywhere in there? I think there’s supposed to be a “you,” unless your edition has a misprint. In poems that have that kind of directness, a critic can talk about or write about them not from a thematic point of view, but from a stylistic or structural or kinetic point of view: How does a poem work? And why does it work, if it does? What’s the machinery involved here? (I use the word “machinery” metaphorically). To me, that’s the nuts and bolts point of view. There are two kinds of criticism I like: one is nuts and bolts, the other is gossip. I think they’re both illuminating: one from an empirical, workmanlike view, and the other one from a superficial point of view, which can be illuminating — like Joe LeSueuer’s book on O’Hara. Do you know it?

Shamma: Yes, it’s beautiful.

Padget: There’s a lot of gossip in there, and it’s actually quite illuminating.

Shamma: Well, even your book on Ted Berrigan is just so fun and beautiful to read, especially sitting in the middle of an academic library. You get to that kind of book and think, “This is wonderful, this is exactly what I want to read.”

Padgett: It’s like looking at a family snapshot album.

Shamma: Right. I saw some actual albums in Emory’s collection of Berrigan and Brainard’s correspondence, which make you feel like you’re learning more from touching artifacts than from reading criticism.

Padgett: To me those are wonderful. There’s a terrific archive of Joe Brainard’s in San Diego. And my archive is up at the Beinecke at Yale — fifty years of papers.

Shamma: Well, in all of the so-called archives, there are a lot of papers. It’s overwhelming. On top of the sort of honesty and “my heart your heart” [a line from Berrigan] mode of the poetry is the sheer number of pages of poetry written. Koch’s collected is what, 754 pages?

Padgett: That’s his collected shorter poems. There are the longer ones as well. Kenneth was prolific. He loved to write and he liked to write long works and he worked almost every day. He loved the act of writing. And then there were all his plays and his fiction. He didn’t publish everything, either. If you look at his archive in the Berg collection in the New York Public Library, you’ll see some of the material he never published.

Ron Padgett reading in Paris, 2003.

Shamma: Looking through Berrigan’s collection, you can see this deliberation over form and the nuts and bolts of it all that isn’t immediately present on the printed page, which to me seems to validate a study of form.

Padgett: Yes. Kenneth himself wrote some formal poems. In his poem called “The Railway Stationery,” each stanza is actually a sonnet. But you don’t notice it at first. Kenneth also wrote sestinas and catalogue poems, and experimented with some other forms. Frank did a lot of that too. Ashbery too. Jimmy less, I think. But what’s really interesting is finding the form that’s particular to each free verse work. When I say “nuts and bolts” I don’t mean ABABCC, I’m talking about how a really shapely, well-made poem in free verse works. That’s truly interesting. The strict forms, the fixed forms, are interesting for a different reason, to me. How do you put yourself in a straitjacket and still dance as gracefully as if you’re not in a straitjacket? That’s a tough challenge, and it’s fun.

Shamma: I don’t know if he’s in a straitjacket, but it kind of happens in O’Hara’s “Aus einem April,” with how that first stanza begins.

Padgett: Yes, it’s the one that begins “We dust the walls.”

Shamma: Yes, and then you end up in what looks like a quatrain, but when you get close to that second formal-looking stanza it’s talking about moving outside and being “turbulent and green.”

Padgett: In that poem, he wasn’t exactly using a form, though in some sense he was, insofar as it’s actually based on a poem by Rilke. The first line of Rilke’s poem is, “Wieder duftet der Wald,” which literally translates to “Again the forest is fragrant,” or something like that. Frank just did a homophonic translation: “We dust the walls.” I haven’t studied it in years, but as I recall, he sort of followed Rilke’s arrangement. It’s something like following a sonnet or a villanelle arrangement.

Shamma: Are you also familiar with “Nocturne”?

Padgett: Frank’s? Yes.

Shamma: Well, I love how he constructs this really narrow poem, and talks about how the buildings are too narrow: in the summer “too hot,” and “at night I freeze.” These are the sorts of poems that I’m interested in — the kind that recreate buildings. The poem complains, “[i]t’s the architect’s fault” while architecting, in turn, an exact replica. And it’s in all of Berrigan’s references to rooms in his The Sonnets.

Padgett: “Is there room in the room that you room in?”

Shamma: Yes, and “Bring me red demented rooms.”

Padgett: That’s a line of mine that he stole.

Shamma: Was it? No! I love that line. I’ve been trying to figure it out for a while.

Padgett: Well, then I have just given you a little secret.

Shamma: Where did it come from?

Padgett: A poem I wrote in 1961. I never published it.

Shamma: Why not?

Padgett: It wasn’t good.

Shamma: So can I ask what the “dementedness” of the room was?

Padgett: I have no idea.

Shamma: Well, I love how the line sounds like what it’s asking for.

Padgett: I’m trying to remember the rest of that poem. I wrote it in the fall of 1961. I was here in New York. I was a student either finishing my first year at Columbia or starting my second. Starting my second year, Ted and I shared an apartment. Maybe it was then that I wrote that. It was right around then. Ted, as you know, appropriated a lot of lines, from Dick Gallup and others.

Shamma: Did you?

Padgett: Less than Ted, but I did some collaged poems and centos.

Shamma: Did you see yourself or your poems registering the city?

Padgett: Yes, the poems did, because I was here and aware of the fact that I was here, but with some exceptions. I didn’t set out to write poems about New York, or poems that reflected New York. I wasn’t Walt Whitman writing “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry” or Vladimir Mayakovsky writing “Brooklyn Bridge” or Hart Crane writing “The Bridge” or Edwin Denby writing poems about the streets of New York — alas. But the fact that I was here had a big influence, of course. It was more of a general, osmotic seeping of New York into my work — things just got in there because I was here, things such as actual places and people, but also energy. The energy of New York was huge. I had come from Tulsa, which actually wasn’t as bad as I say it was, but the energy level was lower there. Of course it was calmer, too, and slower, and in some ways quite pleasant. But it didn’t have the street energy of New York. It had car energy. You could go out and drive a car around fast, you could get in a car and drive straight to Texas, and then turn right around and come back.

Shamma: And enjoy the mobility of being American?

Padgett: You could drive around the whole night — drive around and stop in diners with your friends, have coffee, and talk like crazy. Sort of On the Road behavior.

Shamma: Do you think that when you’re in a place that has an explicit energy, like New York, that you don’t have to create as much energy from yourself? That you can just kind of bounce off of it? Like being in Tulsa, perhaps, might force someone with the propensity to be energized —

Padgett: There was a certain amount of general inertia in Tulsa — artistic too. And one had to sort of push against the inertia. Fortunately, I was young there. I left when I had just turned eighteen. So I was a young, testosterone-driven male, bursting with energy. And then when I came to New York, it was like jumping into a swiftly flowing river. You have to generate more energy just to stay afloat, and if you do, you’re really zooming along. Does that make sense to you?

Shamma: Yes, it makes complete sense to me. I lived here in New York before I moved to Oxford, which has a completely opposite energy level.

Padgett: Yes, I once visited Oxford. It was quiet. But as you know, it’s not just the place you’re living in — it’s the place that’s living in you. If you’re involved in studies, or any type of pursuit that’s intellectual or interior, you can be anywhere, because a lot of your life goes on inside your head, or your spirit. So I wouldn’t knock it so much.

Shamma: Yes, it makes you calm down.

Padgett: It’s great to be calm. Especially here in New York, where everything’s telling you not to be calm. But to get back to your comment about rooms: Jimmy Schuyler is wonderful for the purposes of your work. His poetry’s very sedentary. He’s almost always sitting in a room — giving you the impression he’s sitting in a room, if not giving you the actual information — often looking out a window. He spatially locates himself. Sometimes he’s outdoors, like in Maine, but a lot of his great work takes place with him sitting in a room and looking around. Of course Frank’s work is also quite good that way, although Frank often doesn’t give the impression of being in a room. His conversational poetry happens more on the street. But poems like “Radio” tell you that he’s in a room, listening to the radio.

Shamma: And there does seem to be a frustration whenever he mentions being inside, like in the lines, “Am I a door,” and “The crack in the ceiling spreads” in “Anxiety.” You get the sense that he never wants to be pin-down-able within domestic spaces.

Padgett: Well, he lived in New York in some really dumpy apartments, until his last place.

Shamma: And when he lived in that last apartment, he didn’t write much poetry, did he?

Padgett: No, he didn’t.

Shamma: Why do you think that is?

Padgett: That’s a question that a lot of people have asked.

Shamma: It’s interesting that the crummier apartments gave space for creating poetry.

Padgett: I’m not sure he wanted to spend a lot of time in those places. He liked being out. He liked going to artist’s studios and to bars and to parties, and to openings and art galleries, and friend’s places, and the Hamptons.

Shamma: He seemed to enjoy the mobility that the city offers.

Padgett: He didn’t want to be cooped up. But his last place, a loft, was nice. It wasn’t fancy, but it was very spacious, and I thought it was a terrific place. There was a big view out the window of Grace Church across the street, which he never wrote about. His building’s been torn down, by the way. It’s been replaced by some modern thing. His apartment on Forty-Ninth Street was also replaced. Apparently that was a really awful place, though you could look out the side of the back and see the UN Headquarters.

Shamma: Yes, I read about that one. It was the one with the cockroaches and the beer bottles everywhere.

Padgett: Frank was not a great housekeeper. Jimmy was even worse. But you know, in John Ashbery’s poetry, you’re never really sure where you are, except in the poem “The Instruction Manual.” It’s the only one I can think of where you know where you are.

Shamma: I’m actually not writing about him for that very reason. Even though I know that he is of the same generation, I feel like his poetry is inherently very different.

Padgett: It is. And Kenneth’s too. It’s largely free of specific occasions. Much of it is very artful, often located in the imagination. Frank wrote some very occasional poetry, and by “occasional” I mean not just about birthdays and funerals.

Shamma: Time-based?

Padgett: Yes, time-based, with specific people and specific places. Now, whether or not it’s an accurate reflection of those occasions — in terms of details — that’s neither here nor there really. But it has that feeling — Jimmy’s too — of sitting in a room. You feel he really did that. But with Kenneth’s poems, you have no idea where he wrote them.

Shamma: Except for maybe “One Train.”

Padgett: Yes, and that’s an account of a real trip. But even there, it’s written in reflection, later, not on the spot.

Shamma: Right, like “The Art of Love” would be a complete trip. You have no idea where that was written.

Padgett: Right, that’s like when Ovid wrote his: where was he?

Shamma: But Kenneth did move a lot, right?

Padgett: He got around. He spent a lot of time in France and Italy, and he travelled to China twice, and to Africa, and Greece, and all over Western Europe especially. Mexico, and Guatamala, Antarctica — he got around. He lived in New York City, but also had a house in the Hamptons. He liked the excitement of travel; fresh, beautiful vistas; interesting cuisines; art and opera; and exotic beautiful girls. He was an appreciator of life. He didn’t like the idea of sitting in the same room all of the time. Edwin, though, really can give you a sense of being in a room, especially in his poem “Elegy: The Streets” — you can see him in that room, hearing the sounds of Twenty-First Street outside.

Shamma: And a few of your poems mention street intersections and rooms.

Padgett: There’s a poem of mine called “Poema del City” — there’s actually two of them: “Poema Del City I” and “Poema Del City II.” Two is a very straightforward account of being in my apartment, in the front room, at night, with a bathrobe or housecoat on. I’ve written a number like that.

Shamma: I was thinking of “Poem for Joan Inglis.”

Padgett: That one is a complete fantasy.

Shamma: Is it?

Padgett: A total fantasy. Totally fabricated.

Shamma: I don’t know what to do when I hear things like that. So it’s a fabricated landscape of a room — it’s a fabricated space?

Padgett: Yes. My prose poem called “My Room” — do you know that one?

Shamma: Yes I do.

Padgett: That one’s very much about being in a real room. Actually, the new book that I just put out has a poem that talks about sitting in a room in the house that my wife and I have in Vermont. And my grandson, who was just a very little baby at the time, is asleep in the next room. The poem is about the experience of sitting in the room and thinking of my grandson on the other side of the wall.

Shamma: I have to ask the really simple question about the word “stanza” meaning room, and the material metaphors you all use — like your sense of “the machine,” and Ted Berrigan’s sense of words being “bricks.” He even says at one point that he thought of his stanzas “being rooms.” You get the sense of a construction being built.

Padgett: Right, building a house.

Shamma: Yes. Does the shape of a room come into play in shaping the actual stanzas written out of rooms?

Padgett: Not consciously, no. I mean, it’s okay to work that way, but I don’t seem to be interested in doing that. I’m sure I’m influenced by the room I’m in, just like you’re influenced by what you had for breakfast. Like in Vermont, the room that I’ve written a lot of poems in is what I call my study. It’s a fairly small room with a pitched roof, and it’s kind of cozy. It’s just my room — the only one I’ve ever had like that, in my adult life. That cozy space is conducive to a certain kind of privacy that fosters rumination, or a kind of dreamy poetic state. You’re safe, it’s quiet, you’re alone, and it’s very pleasant to be in that room. So it helps me.

Kenneth wrote in his living room. As a professor at Columbia, he had a very nice large apartment, with a big open area with French doors. He had a table there, facing a wall, but not facing a window. That’s another thing you might want to think about: Jimmy looks out the window when he writes, and he’s able to do it. But a lot of other writers, I’ve heard, think it’s murder to have a window right in front of you.

Shamma: I’ve seen pictures of Frank O’Hara and Ted Berrigan’s desks, and Berrigan’s was sideways against a wall.

Padgett: The brick wall?

Shamma: Yes, and O’Hara’s was facing a wall.

Padgett: Ted, just after he wrote The Sonnets and had just started C magazine, had a desk that faced a wall, and on his right was an exposed brick wall. I’ve often set up my desk so I don’t look out the window. But in Vermont, I can look to my left and out a window. Otherwise, straight ahead of me is just wooden pine boards. But I still spend a lot of time looking out that window.

Shamma: I wonder if your poems are accordingly different — your Vermont poems.

Padgett: I don’t know. But here in New York I’ve had my desk facing a wall since I moved into the apartment, in 1967. Apollinaire, too — his study was cramped. He was a bulky guy, cramped into his garret’s narrow space, with his writing table facing a wall. The window was to his left, high above eye level.

Shamma: It’s interesting, formally, to consider how the wall informs poems. Looking at, or being aware of the dimensions of the room can inform the dimensions of a poem. But also the turning away from the other space in the room, and writing a very personal poem, talking to a “you” but looking at a wall — it’s a strange kind of energy. I’m not really sure what to do with it.

Padgett: An interesting question is: What happens to the eyes of the writer as he or she is writing? Do they look at the wall? In Hollywood movies they do. I’m not sure I do. Usually I’m looking down at the page, and there’s a “room” there on that page, or at least a floorplan. Or if it’s a computer screen, it’s a window. And I’m looking through that window. That’d be another interesting approach: to see the computer screen as a window.

Shamma: Yes, I was looking at your essay on computer writing and what kind of art it might produce.

Padgett: That’s a really old piece.

Shamma: Yes, and it has a footnote about how funny it is that this innovative computer-based writing didn’t actually end up happening.

Padgett: That was a concept that my son and I came up with when he was a kid. I thought there was going to be a brand new kind of writing. It never happened. It’s interesting though that it didn’t happen.

Shamma: I was thinking about it in terms of graphic design, and wondering if that has become a new kind of writing — less manipulation of words, and more with what the screen in general allows.

Padgett: I predicted a writing that would be a synthesis of visual art and music and everything. That’s an avant-garde idea from way back, and its realization was deemed imminent. Then it just didn’t happen, because computer companies made it impossible for the average person to program. The Mac and the PC were the death of that possibility. If you go back to earlier programs, written in BASIC — even the Atari 800, built mainly for games — you could actually program an Atari, and it was fun.

Shamma: Yes, it’s all become very consumer, end-product based.

Padgett: The technocrats took it over and did some sexy, attractive things, but made it so that nobody could program the more advanced computers except advanced programmers.

Shamma: I saw an interesting advertisement for the iPad, pitching that it was smaller, thinner and lighter to get out of the way, so that you can have more life.

Padgett: It’s to get you further hooked on it. Try to withdraw from it and see what happens to your life. My hard drive crashed a couple of weeks ago. I was without a computer for a few days, and I found myself yearning for it. Like drug withdrawal. And I realized: Ah! They have you hooked. You have to upgrade all the time, and if you don’t, you suffer. It’s like taking more and more heroin. They have you psychologically addicted.

But to get back to the room idea: Take the physical structure and components of the room and see what poems, or parts of the poem, relate to parts of the room. Like the poem as “window” — Apollinaire has a poem called “The Windows.” The ceiling — what does the ceiling, the feeling of the ceiling, and the presence of a ceiling do to someone writing in a room? If you’re writing in a room with a high ceiling or a low one, or a tin ceiling — like this one here at Di Robertis — what does that do to you? And also the dimensions and proportions of the room — what do they do to one’s feelings and thinking? Also the walls — what are they made of? What do they look like? And the floors! Floors are more important than ceilings. Why is that? Why do I think that?

Shamma: Well, because of stability.

Padgett: Yes, but also I look at floors. I don’t look at ceilings. And I don’t walk on them, not very much!

Shamma: You don’t need a ceiling as much as you need a floor?

Padgett: No, you don’t. If you don’t have a floor, you’re in trouble. But then there are certain kinds of floors, and the way you feel walking across them. Walking across the beautiful marble inlaid floors in the Siena Duomo is different from walking across the spruce-board floors of my house in Vermont. What does that do to the feeling about being where you are? Our responses can be somewhat subtle and even subliminal, but they’re interesting to think about. Then there are the shutters and blinds and curtains —

Shamma: See, these are domestic details. I’ve been looking at layouts and floor plans: like railway apartments and the lack of space they present, and how that lack of space comes into a poem. Or like your “Crazy Compositions,” or [Berrigan’s] “Tambourine Life” that are super spread out. Or even Berrigan’s “Train Ride” — these are long poems that came to be written out of smaller spaces. I’m not sure about where your spread-out poems were written.

Padgett: The three poems you mentioned — in Crazy Compositions — were written in Vermont after spending nine months in New York City. I wrote them in a couple of days. I put them together — I constructed them, I actually hand-wrote part of them — a few days after getting to Vermont, where the space felt incredibly open. I put them together up there, but it wasn’t only because I was in Vermont and could be in the great outdoors. It was because I felt an urge to write that kind of poem. Maybe it was just coincidental that I did it right after getting to Vermont. I could’ve done it here in New York. Ted wrote those kinds of poems here: “February Air,” and a poem called “Bean Spasms,” and “Tambourine Life.”

Shamma: Of his longer, strangely laid out poems, the one that I’ve considered is “Train Ride.” I like how, in that poem, the compartments of the train feel mapped onto the page.

Padgett: “Train Ride” is episodic. If you walk through the compartments of a train as it’s moving along, there are different stories going on in each car. For some reason, I think of a line from The Jew of Malta, Marlowe’s play: “infinite riches in a little room.” The idea that you can have so much in a little space —

Shamma: Yes, it sounds much like John Donne’s line: “We’ll build in sonnets pretty rooms.”

Padgett: But Train Ride was written in response to a prose work by Joe Brainard.

Shamma: Wasn’t it written in response to a porn magazine?

Padgett: No. Joe wrote a work also called “Train Ride,” an account of taking the train from New York City to the Hamptons. He gave it to Ted, and Ted wrote a response — a sort of conversation with Joe. So in a sense, there were two people in that compartment while Ted was writing.

Shamma: Yes, the “you” of that poem is very specific.

Padgett: It’s dedicated to Joe.

Shamma: Yes, and the poem ends with lines that say “Thank you for being with me on this train.”

Padgett: A very nice work of Ted’s, and a nice edition. Ted got Joe to do the cover image, and it worked out well.

Shamma: Do you miss those kinds of productions? Those kinds of tactile publications?

Padgett: Actually, there weren’t that many. Most of the underground book productions in the early sixties were rather rough and ready, mimeograph editions, like The Sonnets in 1964 and my first book, In Advance of the Broken Arm.

Shamma: Great Balls of Fire wasn’t your first book?

Padgett: No, it was my first book book (1969), that is, with a big publisher. In Advance of the Broken Arm was published in 1965. We didn’t get into better production values until later. Come to think of it, the 1967 Grove Press edition of The Sonnets was not a great production: saddle-stapled, with minimal attention to design. Train Ride was published eleven years later, and it was a nicely designed and printed book. I like good production values, but I don’t like fussy ones, where the book exists just to give a book designer a chance to show off.

Shamma: Well something I liked about looking at the original publication of The Sonnets (rather than looking at them in the recently published Collected Poems), was that there is one sonnet per page, smack in the middle of each page. So you really get the sense of these block compositions, shaped by the page. When you see them trailing one after another, they don’t come at you the same way.

Padgett: No, they don’t. Ted liked the space around them. He was extremely conscious of the way poems look on the page.

Shamma: Are you?

Padgett: Yes, I think it’s important, but you can’t always control it. For instance, when you compose something and go to print it out, it’s coming out on what is usually a letter-sized piece of paper. And if it’s published by a print magazine, they have different fonts and different trim sizes. You can’t control it much. And it’s just as bad online.

Shamma: What about collaborations?

Padgett: What about them?

Shamma: How does the composition play out there? Like your collaborations with George Schneeman?

Padgett: There it’s super-important.

Shamma: How are those created? I’m thinking about the poem with the block illustrations and then the narrative commentary/poetry underneath the blocks and cartoons.

Padgett: George and I worked in a lot of different ways. In terms of the materials, we had collaborative drawings and collages, canvases, mixed media pieces, silkscreens, ceramics, etc.

Shamma: Where did you get the feeling that that was possible?

Padgett: I think I was inspired by the working relationships of the Dada and Surrealist painters and poets, and the fact that Francis Picabia was both a poet and a painter. But the first collaboration I ever saw in person was Frank O’Hara and Larry Rivers’s series of lithographs, called Stones. I’d already seen some poem-paintings by Kenneth Patchen in his books. Also, Joe Brainard and I had done a collaboration in high school, before I knew about the history of collaboration.

Shamma: He was with you in kindergarten, right?

Padgett: Maybe kindergarten, but I don’t remember. I have a picture of him and me in first grade together.

Anyway, George and I used not only different media, but also different working methods. Sometimes when we were working we were living hundreds or even thousands of miles away from each other, so we’d mail things back and forth. He was in Italy once and I was in Vermont and we collaborated on a series of colored pencil drawings. It’s called “The Story of Ezra Pound,” and it’s a wonderful piece, but it’s never been published. So don’t go looking for it.

Shamma: Why hasn’t it been published?

Padgett: I don’t know. It would take a fine production, because it’s in colored pencil — very subtle, and only seven pages long. But it’s really terrific. Both George and I were surprised by how it came out. Often, we worked directly in the same room, on the same surface at the same time. In fact, in later years, that’s how we did most of our work together.

Shamma: Together in a room?

Padgett: Yes. For example, at one point we were doing charcoal and egg tempera works on large pieces of paper, five or six works at the same time, moving around the room, back and forth.

Shamma: Which works are those? Are they published?

Padgett: They’ve been exhibited. In fact, one just came back from a museum. But they’re large — they’re hard to publish.

Shamma: So they are spatial pieces?

Padgett: One is almost as wide and tall as that wall over there: a pretty good size. The Center for Book Arts did a show last spring of poets and painters. The show then traveled down to the Museum of Printing History in Houston. Anyway, George and I worked directly, simultaneously, sometimes at the same time on the same piece of paper. There was a lot of variety in our work overall.

Shamma: There’s no poetic persona there, though, right? It’s not an “I” to a “you.” I was thinking about this because a lot of collaboration throughout all of this “New York School” poetry challenges the energy of individual encounters. When it’s two artists to one audience, I don’t know if it’s a fractured voice that emerges, or a less understandable one, but I find that the collaborative poems are a lot more difficult to read.

Padgett: They can be more fractured, but they also tend to be more light-hearted, more “fun,” because we had a good time writing them.

Shamma: Do you think that there is an absence of persona in a lot of the poetry that was written around St. Mark’s Church?

Padgett: You mean in collaborative poems?

Shamma: In even the single-authored poems, is the “I” the poet?

Padgett: I think it’s dubious to assume the “I” in a poem is the poet. Most poets know that they’re performing. Johnny Carson doing The Tonight Show is not exactly Johnny Carson. You see what I’m saying? And certainly the collaborative pieces are showing the persona of each poet, or artist — but then in the process, a third persona gets treated, their shared persona.

Shamma: So it’s a dangerous trap to fall into — thinking anything more of the “I.”

Padgett: Yes. But of course there are a lot of people who, when they write poetry, think that when they say “I” they mean themselves exclusively.

Shamma: Ted Berrigan says that.

Padgett: He says what?

Shamma: He says that the “‘I’ is not ‘Prufrock’ in my poems, it’s Ted Berrigan” (Talking in Tranquility).

Padgett: Obviously Prufrock is not Eliot. I would bet that there’s always some percentage of the “I” that is not the poet, but is the “I” of the poem. Making art is not the same as talking to your psychoanalyst.

Shamma: Like your poem “Little Dutch Diary.”

Padgett: That’s not a poem; it’s a diary.

Shamma: So that “I” is you.

Padgett: Pretty much.

Shamma: And that can happen because of the title?

Padgett: Yes, it’s a diary of a real trip. And I was trying to just write down what happened. But even there, I’m aware that I’m writing. I’m not writing a diary just to keep a diary. I’m a writer. Did I know that I was going to publish it? No. Was I aware to some degree that it might turn out to be a work that I would publish? Yes. When you’re a writer and you’ve published a lot, you are always aware of the possibility of publication. But I try my best to forget that.

Shamma: Were you teaching alongside all this writing?

Padgett: Some of it.

Shamma: So after you left Columbia University, you taught?

Padgett: As soon as I graduated Columbia with a BA, I swore I would never set foot in a classroom again as long as I lived. Kenneth Koch wanted me to go to graduate school and get a degree so I could teach at Columbia. And I told him I appreciated it, but I just didn’t want to do that. He was nice about it. He even helped me get a Fulbright a year later. But on the Fulbright, I didn’t even go to classes.

So I got out of college in 1964, and in ’64–’65 I was around New York. My wife was working in an office, and I had gotten a grant of $1,500, which was enough to live on for a year. We were living in an apartment on West Eighty-Eighth Street, and the rent was ninety dollars a month. Then my wife and I went to Paris for 1965–66, and when we came back to America she was pregnant, so we went to Tulsa to have the baby. We had no money, no apartment, no jobs.

Shamma: So that’s why you went to Tulsa?

Padgett: Yes. Kenneth got me an emergency grant of $500 to have the baby. We got the poverty rate at the hospital clinic. Having the baby cost one hundred dollars.

Shamma: What do you mean, “the baby cost one hundred dollars?”

Padgett: I had to pay the hospital one hundred dollars. They wouldn’t let us leave with the baby if I didn’t pay. Then we moved back here to New York with what was left of that grant. I got a number of freelance jobs: proofreading, writing jacket copy, and doing some readings. Our apartment was only fifty-three dollars a month, and generally it was very cheap to live in those days, if you didn’t mind scrimping a bit. Then I started teaching poetry writing to children because Kenneth Koch tricked me into doing it. I did that on and off for about nine years — a lot of it here in New York, but also around the country. So yes, I found myself back in the classroom, especially the elementary school classroom.

Shamma: I read Koch’s Rose, Where Did You Get That Red?: Teaching Great Poetry to Children, and you get the sense of joy in teaching kids that age.

Padgett: He and I were doing it simultaneously at certain points at the same school, and he was really a great mentor. After nine years, I did begin to burn out. I also taught a writing workshop at the St. Mark’s Poetry Project.

Shamma: And you ran it?

Padgett: Later, I was the director of the Poetry Project for two and a half years. I also did some teacher training workshops all over the country. And then the next teaching was at Columbia — the undergraduate level. I taught a course called “Imaginative Writing,” subbing for Kenneth. He was going on sabbatical and he wanted the course to continue, so Columbia hired me to teach that course for a number of years. Then Brooklyn College invited me to teach for a year — actually two semesters spread over two years — in their MFA poetry program. But that’s been about it.

Shamma: Has teaching influenced your writing?

Padgett: I think that teaching little kids probably did. I don’t think teaching at the university level influenced my writing at all, but I enjoyed it.

Shamma: Do you think the poverty of those earlier years influenced your writing? I was thinking about Ron Silliman’s blog posts, where he talks about third- and fourth-generation New York Schools. I look at the schools he outlines and think that they can’t be the same schools, because the economics of the scene changed so much.

Padgett: It’s not economically feasible to be a poet in New York these days, unless you have a trust fund or you’re willing to share a place in Bushwick with three other people. When I was the director of the Poetry Project, in 1979 and ’80, I wrote a letter to one of our city officials to complain about the fact that this neighborhood that we’re in now, where the Poetry Project started — a lot of poets lived here — was getting gentrified. It was starting to be called “The East Village.”

Shamma: What was it called before?

Padgett: The Lower East Side.

Shamma: So adding the “village” to it was a way of gentrifying it?

Padgett: Yes. The “village” was really the West Village (Greenwich Village), a neighborhood that formally had been full of artists and writers. But the Lower East Side had old-world ghetto associations. The real estate agents cleverly changed the name, and suddenly the rents went up.

Shamma: Like Häagan-Daaz?

Padgett: Exactly. I’d like to find out who their consultant was on that, because it was a smart person. But it ruined the neighborhood for people looking for cheap rent. So I wrote a letter to the city officials, saying that a lot of the young poets who want to come to New York are now not able to, or they’re forced to live in Brooklyn, which at the time was considered like living on Mars.

Shamma: I’m reading Patti Smith’s Just Kids right now, and she mentions that sense of it being far away.

Padgett: Almost no one wanted to live in Brooklyn. It seemed so distant, and so dead.

Shamma: So it was forcing this kind of exodus?

Padgett: Yes, it was a kind of forced exodus. I got a response from the city official saying that this kind of exodus was going to be wonderful because it was going to revive and energize the outer boroughs. I thought, “That’s an interesting idea, let’s just send everybody to Siberia.” The outer boroughs were not Siberia of course; I exaggerated. But it turns out that Williamsburg has been energized, and Greenpoint and some other places. But it took thirty-five years. Hello!

Shamma: It has happened quite slowly.

Padgett: It was no fun for people who were forced to leave Manhattan, or who just gave up and went back to Wichita, or who never came at all. I feel sorry for them, because when I came here it was so much cheaper to live. Of course, you had to put up with a lot. This neighborhood was occasionally not that pleasant to be in: muggings, burglaries, drug addiction, shootings, and just general ratty-ness. That part was not so much fun.

Shamma: But you wonder how that seeps into the poetry, or how it colors it. How does that kind of disconnect between your generation and later generations emerge? When I read what they are calling fourth-generation New York School poetry against second-generation New York School poetry, there’s a real difference. The newer poetry seems a lot more formed.

Padgett: It seems to me that a lot of younger poets are more overtly intellectual. They’re coming from university situations, and they’re smart. But sometimes it’s not working in their favor.

Shamma: What kind of poetry are you reading now?

Padgett: I’m not on any jag right now, but I am going to take part in a group reading for Tim Dlugos, which is happening next month, so I had to decide which poem I was supposed to read. He was a very interesting poet who died some years ago. He was part of this community. So I was reading his work this morning. Every once in awhile I’ll go on a reading jag — in summer especially. A couple of summers ago — four or five ago — I reread all of Andrew Marvell, the English poems, that is.

Shamma: Is that while you were writing “How to Be Perfect”?

Padgett: No. I wrote “How to Be Perfect” in 1988.

Shamma: Oh really?

Padgett: The title poem, yes. The book with that title came out much later. But the poem was written in ’88.

Shamma: I love that poem. It’s a lot like O’Hara’s “Lines from a Fortune Cookie.”

Padgett: It was fun to write. So I’ll go on reading jags like that, picking some poet and reading him or her intensely over a period of months. One summer it was George Herbert. I also get books in the mail, especially from younger poets, so I try to at least glance at them to see what’s up. There are friends of mine who won’t stop writing, so I have to read all of their new books, which fortunately are usually pretty good.

Shamma: Do you see your poetry changing?

Padgett: I hope so. My publisher, Coffee House Press, said they wanted to publish my collected poems. So I went back over all my work and thought: What would this book really look like? Yes, the work certainly changes, but I was taken aback by how similar some of the pieces are. I rediscovered a poem that I wrote many years ago that’s amazingly like a poem I wrote two years ago.

Shamma: Consistency of character maybe?

Padgett: Well, I don’t know. I can’t claim to have any character at all. I was really surprised that this poem existed. It was almost like I had predicted what I was going to be writing later.

Shamma: It sounds like something that needed to come out.

Padgett: It wasn’t so much what I was saying — it was the mode. It was a poem in which I was having a conversation with something very big and diffuse. The first one was about having a conversation with the city of Tulsa. The second one was about having a conversation with a cloud. So it was like Frank O’Hara’s poem, “A True Account of Talking to the Sun at Fire Island,” which may have been the unconscious connection behind my two poems.

Shamma: Yes, and the sun says, “always embrace things, people earth / sky stars, as I do, freely and with / the appropriate sense of space.”

Padgett: Isn’t it beautiful?

Shamma: Yes, that line to me is the connection between all of this kind of poetry.

Padgett: “Guarding it from mess and message” [Berrigan]. I may have misquoted that, but there’s a similarity there — a fine line between being too open and too closed.

Shamma: He really seems to straddle that line. On that line, can I ask you how you thought beatnik poetry might have gotten interwoven into your work?

Padgett: Allen Ginsberg’s Howl was the first book I ever read that really excited me about poetry. I was about fifteen, and I was astounded by it. For me, it came at the right time.

Shamma: I have to ask you if you’ve seen the recent movie.

Padgett: I have not seen the movie. I would hope to some day. I heard that the actor is a very nice guy.

Shamma: Well, the reason I ask is that they animated the poem.

Padgett: Usually movies about writers don’t work very well. Some of them really stink. But there have been a couple of okay ones. Certainly movies about the Beat Generation have tended to be awful. But Ginsberg was the big inspiration for me. I had just discovered Whitman, but he of course was dead. I couldn’t believe that this guy Ginsberg was alive and writing like that. And then, of course, there was Gregory Corso. That all led quickly to discovering LeRoi Jones, Robert Creeley, Charles Olson, Paul Blackburn, Frank O’Hara, and others. Early on, in high school, I wrote blatant imitations of free-wheeling beatnik poems; jazz poems too. I’d listen to Miles Davis and write poems inspired by his music. Anyway, the Beats were a big turn-on for me. They opened a door.

Shamma: They may have made it possible to think that just being exciting was enough.

Padgett: They were filled with excitement about the universe, like a mystic or an adolescent. And I thought Corso’s poems were quite funny — witty in a strange way.

Shamma: “Marriage”?

Padgett: “Marriage” came a little later. I was thinking about Gasoline, his first book. But yes, I loved “Marriage.” I thought it was terrific and very funny.

Shamma: And simultaneously tender.

Padgett: Yes, in an odd way. Allen’s diction opened me enough to be receptive to Frank O’Hara, and even to Kenneth Koch a little bit — although that came slightly later — because I had a sense of humor, but I didn’t know that I could use it in poetry. When I was in high school, most of my poems were very serious, Black Mountainesque. I got opened up further, though, when I came to New York and started studying with Kenneth, and reading the great books of the Western world in his class. Seeing him talk about them made me realize that wit was something that was quite wonderful to have in your writing. Not the only thing to have, of course, and I don’t mean jokes or humor. I owed a great debt to Allen, and to Ferlinghetti. In high school I read Pictures of the Gone World and A Coney Island of the Mind, and I was quite inspired by them. I’ve never given Ferlinghetti enough credit, but I’ve always known I owed Allen a lot, not only for his poetry.

Shamma: From what I’ve read, he was a very motivating spirit.

Padgett: I wrote him a letter when I was in high school and said, “I’m starting a little magazine, would you send me some poems?” And he sent me his poem “My Sad Self,” dedicated to Frank O’Hara. He was so nice. I told him I was going to go to Mexico, and he said, “Yes, go to Mexico! Dig the streets! Dig the whores!”

Shamma: Did you dig it?

Padgett: Well, no, I did not dig the whores of Mexico City. I was sixteen, terrified of even the idea of talking to a prostitute! But the general “dig the streets” idea, yes.

Shamma: But you did go to Mexico then.

Padgett: Yes, several times. And he was wonderful when I told him I was coming to New York to go to Columbia. He said, “Call me when you get here.” Virtually the only people I knew in New York were Allen Ginsberg, Joel Oppenheimer, LeRoi Jones, Fielding Dawson, and Paul Blackburn.

Shamma: Not a bad crowd you had!

Padgett: All these people — I was pen pals with them. So I called Allen when I got here. I was up at Columbia and he said, “Come down and visit!” So I got on the subway and came down. I went to East Second Street and knocked on his door, and he was very kind to me. He lent me some books; he gave me advice. He was very nice to me my entire life. His singing was a little bit hard to take, but I never stopped admiring him. I was very aware of what a generous spirit he was, both with his time and with helping people. He lived around the corner from my apartment, so I used to see him at the fruit stand at night. We worked on different things together here and there. We weren’t close and continuous friends, but I knew I could always call on him. We even wrote two poems together, one of which wasn’t too bad. But I really admired him. Do I like all his poems? No. I don’t like all of anybody’s anything, but the good ones are really good. The people who characterize him as more of a media figure — I don’t know about that.

Shamma: They’re just jealous.

Padgett: Absolutely. Anyway, I owe him a lot. Kerouac’s On the Road, too, was a huge turn-on for me, and not just because of the lifestyle it describes. His writing has tremendous energy, and at his best he was a very good stylist — Dr. Sax, “Old Angel Midnight,” and “October in the Railroad Earth” are all wonderful. The poems in his Mexico City Blues: I could “dig” them but I never quite got into them the way other people did. The Dharma Bums: I loved that book. But Kerouac got mad at me because after I printed a poem of his in my little magazine, he sent me more poems. I printed some but rejected others, so he got mad at me, after which I was afraid to meet him.

Shamma: How did you start that magazine?

Padgett: I’d seen LeRoi Jones’s magazine Yugen and thought, “This is not that complicated.” So I went to a printer in Tulsa and found out it wasn’t that expensive, either. Then I and my buddy Dick Gallup (who lived across the street and was one year older than me) along with Joe Brainard (who was our art editor), we just wrote to writers we liked, asking them for work — to Kerouac, Ginsberg, and even e. e. cummings. It was amazing how many replied. We were only sixteen or seventeen years old.

Shamma: Did they know that?

Padgett: Yes, we told them up front — I think it was our only selling point. It hooked them into reading our letters. The other day I was in the library at Harvard, where I saw two of the correspondences I had with cummings. God was I arrogant! I was shocked by my teenage arrogance. Boy oh boy.

Shamma: And you spent the rest of your life being “never so arrogant again.”

Padgett: You could call it chutzpah if you wanted, but I’m not Jewish, so it doesn’t work very well. Let’s say I was bold.

Shamma: Are you working on anything right now, is that why you were looking at the e. e. cummings papers?

Padgett: Ashbery and I were doing an evening on Frank O’Hara at Harvard, so I thought I might as well go see these documents. It was shocking, but it was fun.

Shamma: Well, this has been fun. Thank you.