Ambivalent romantics and jagged kinesthetics

A conversation between Angela Peñaredondo and Jai Arun Ravine

Editorial note: The following is a transcript of a conversation between two artist-poets on their recent publications. Jai Arun Ravine, director of the short film Tom/Trans/Thai and author of The Romance of Siam: a Pocket Guide as well as แล้ว and then entwine: lesson plans, poems, knots, specializes in genres of blended identity, gender, and race. Currently based in Philadelphia, they take the time to sit down and discuss the themes of orientalism, colonialism, and tourism prevalent in their work.

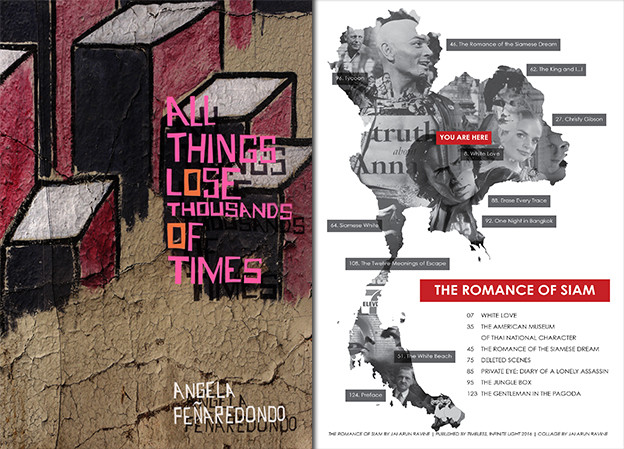

Angela Peñaredondo, Pilipinx/Pin@y poet and artist, resides in Southern California and has work in California Journal of Poetics, Drunken Boat, Southern Humanities Review, and numerous others. As the writer of Maroon and All Things Lose Thousands of Times, Peñaredondo shares her/siya own insight on the concept of displacement — locational, spiritual, and bodily — and how poetry and other media can intertwine to better represent it. — Brianne Alphonso

Angela Peñaredondo: When I discovered your book, แล้ว and then entwine (Tinfish Press; 2011), I was excited to experience poetry that read and felt like an innovative hybrid of incantations and mythos with its visual maps and diagrams of text and shape. When I flipped through The Romance of Siam, its crimson and gold pages of a subversive, pocket-size travel guide, I was ecstatic.

As a first-generation immigrant, I too am quite familiar with the romantics and ambivalence when returning to the place of birth or birthplace of family. It is a rough awakening when faced with the complications of birthplace occupied by tourism and capitalism, along with the Western world’s implementation playing lead in market, economy, and popular culture.

During one of your interviews, you reference Edward Said’s seminal Orientalism as historical groundwork for The Romance of Siam. So I’m curious if it was Said or someone or something else that inspired you to use the framework of a travel guidebook as a creative platform? Was it an idea that came immediately or was it a gradual process of trial and error?

Jai Arun Ravine: What led to the travel guide format was many years of artistic practice and introspection with regards to being a child of an immigrant, and “returning” at particular points in time in my development as an artist, and the feeling of being a tourist to myself. It grew from the realization that others of non-Thai descent often had the most access to or mastery of Thai culture and being. I’m also working through my own romanticism, nostalgia, and orientalism for an “authenticity” of self that can never be recovered. I think that guidebooks try to sell you an authenticity of place, and I wanted to explore how that transaction or system of cultural exchange is, in and of itself, inherently empty.

Peñaredondo: Lonely Planet, Rough Guide, Fodors, etc. As a traveler, there’s a part of me that has found them useful but there is certainly that part I detest, such as their Western-centered approaches to culture and travel. They have a way of compartmentalizing a country’s landmarks, natural geographies, people, and even the subculture and the cuisine. All of this is packaged into an easy-to-read, aesthetically inviting object filled with abstractions of the idealistic other like a coffee table book. Yet, in The Romance of Siam, you subvert the travel guide concept through intricately incorporating a camp sensibility. I’m thinking of Susan Sontag’s Notes on Camp where she says, “Indeed the essence of Camp is its love for the unnatural: of the artifice and exaggeration.”Sontag continues, “To camp is a mode of seduction — one which employs flamboyant mannerisms susceptible of a double interpretation; gestures full of duplicity, with a witty meaning for cognoscenti and another, more impersonal, for outsiders.”

One of my favorite characters in your book, Yul Brynner (who I grew up watching) is such an iconoclastic face in Hollywood cinema, known for his racebending roles. In your piece “The Romance of the Siamese Dream,” it’s noted that Yul Brynner has performed as the King (from The King and I) an astonishing 4,634 times. He proceeds into a fetishized ethnic performance of confronting a tiger and a rice cooker. There is an erotic charge when he enters them (head first too!) as if they were portals into more racebending performances. Your character of Brynner is also constantly disrobing in order to expose his chest hairs, and engages in homoerotic acts and dialogue such as in the piece “Exotic Leading Man.” This happens throughout the book with other figures like Jim Thompson (an American businessman who capitalized on the Thai silk industry and, in your characterization, “created” Bangkok’s famous floating market to attract white tourism) who fights with Yul Brynner over the King’s part in the musical version of The King and I.

In your strategies of humor and theatricalization in creating figures in our book-as-camp, you expose America’s experience of orientalism as similar to Black minstrelsy. In turn, you disrupt the American performance of orientalism by becoming both the director and choreographer of these racialized and gendered performances. Do you consider the aesthetics of The Romance of Siam camp? And if so, when and how did you decide to integrate this camp style of the travel book? Were there non-American camp influences? Cinema has such a powerful influence in the book. Can you tell me a little about that? Of course, please let know if I’m completely missing the mark …

Ravine: I wasn’t consciously considering camp during the generation of this work, but I like what Sontag says about gestures of duplicity as seduction. I think that the kind of orientalism I’m writing about when it comes to white tourism or white obsession with Thailand is one that is built upon this notion that Thailand has two faces, or encompasses opposites, that there is something simultaneously holy, innocent, dirty, and sexy about the place that is in fact part of its romance, part of its attraction, part of its lure.

I hadn’t really thought of it as camp, but you are on point with the observation that my uses of humor and theatricalization attempt to disrupt the performance of orientalism. My interest in dramatizing encounters in the book stems from this notion of blurring fact and fiction, or the desire to create a fiction around oneself, which I found to be an integral part of the orientalist engine. I think my uses of humor stem from the absurdity of the subject matter, and my desire to exaggerate that absurdity to the limit within a kind of theater or cinema. The homoeroticism and transgender identification among some of my characters draws from my desire to “queer” the dynamics of colonial desire.

How we are talking about seduction and performance and gender here in relationship to colonization and decolonization, and how the engines of colonization and orientalism impose or extract performance or sex from the body, might be an interesting frame through which to introduce your book, All Things Lose Thousands of Times. I want to start with the body in your poem “Black Tigers,” which is also a body scattered — scattered viscerally across a landscape by suicide attacks, but also scattered metaphysically through time by memory. You write:

But when she’s strapped, how she can slither

through any damn hole, any dark line

of in-between. For country, she says, I shall be

severed. Spread with voracity, then refined to

seeds and meat. This land. All hunger, girls.

To write about the experience of a femme body of color is to write about colonization, war and trauma. This poem ends with a “smooth leg” in “full gleam.” It reminds me of the main character in Nnedi Okorafor’s speculative fiction novel Who Fears Death, Onyesonwu, a sorcerer who can shape-shift (mostly into a vulture) and also repeatedly faces death, dies, and returns. The jagged magic I see in your writing is akin to Onyesonwu’s sorcery, an energy that moves beyond death, past death, and through pain, blurring bodily boundaries and the veils between realms. I see the brokenness, but I also see how you touch the beauty in the broken. For whom is this body? For whom is this story? For whom is this body splayed? For whom is this body restructured and reimagined by way of your poetics? For whom is this beautiful?

Peñaredondo: I’m flashbacking to the Tamil film, The Terrorist (1998), directed by Santosh Sivan. I remember watching it on a small box TV in a closet-sized room in San Francisco around 2002. I was incredibly moved by it. In short, the film is about a young woman (Malli), who is a guerilla soldier that volunteers to become a suicide bomber. Thinking of your questions for, who is this body, this story splayed, I can’t help thinking how death in many countries translates as victory or devotion. On the subject of domination, bell hooks says, “In our nation masses of people are concerned about violence but resolutely refuse to link that violence to patriarchal thinking or male domination.” In an interview with Eve Ensler a couple years ago, hooks states, “it is domination that separates us from our body.”

I thought about the film The Terrorist months after “Black Tigers” was out in the world. Malli’s primary mission to sacrifice her body (note, the cause is never specified in the movie) changes because she becomes pregnant. Malli begins to act more independently rather than acting as part of her military collective. Her physical gestures express as if she is finally entering, taking control of her body, and, for the first time, questioning that ownership, which now includes the life inside her and how it complicates her mission as a soldier. Her resistance begins from the inside. Because the film is quite low on the spectrum of violent action-packed visuals, the cinematography focuses on the details of Malli’s interactions with the natural environment and the people around her. At times, scenes feel meditative and intense.

These moments in the film are visually and spiritually beautiful to me, in spite of its connections to war or terrorism. I believe that violence does force mental and physical disembodiment, but I also want to believe that brokenness is also connected to wholeness, to what was or is the complete body of a person, a complex individual. As much as I want to reveal the violence of dominance, I want to both critique and honor that wholeness in a poem like “Black Tigers.”

Jai, I understand you are also a dancer and a performer? And I understand that a huge part of that medium entails developing a wide range of body expressions and motion as well as a heightened awareness of corporeal intelligence. In The Romance of Siam, it feels that the Thai voice(s) mostly communicates through the non-Thai characters in the book. What was your reason behind this decision and was it difficult for you? Did your artistry as a performer assist you in entering these bodies and speaking through them?

Ravine: Yes, the “Thai” voice, if there can even be one (or perhaps the voice of the “I”), is speaking through whiteness, through white figures, not the entire time but almost entirely. Was this difficult? It was gross, but there were moments when I identified with the white orientalist voice, or with Nicolas Cage, or Christy Gibson. There were moments when I hungered for their proximity to Thai-ness because I thought it could bring me closer to myself. And because I was feeling like a tourist to myself, like a tourist to my Thai-ness, I guess I wanted to challenge myself to inhabit the disgusting site of the white male body, inhabit its absurdity, and, as you say, choreograph and direct their exchanges and performances, and disembowel their bodies from the inside out. I think that my dance training, particularly the improvisational practice of embodying kinesthetic states, translates into how I embody certain pieces of the book when I perform them for live audiences.

But in what way are my performances of whiteness comfortable or accessible or “safe” to white audiences and white guilt? As a queer nonbinary person of mixed race, I’m pushing myself to contemplate this more within my artistic and social practice. I know how necessary it is for women and trans writers of color to restructure and remap and rebody within our craft. And when we do this, someone is usually watching. That someone is the reader, but that reader is also white supremacy and heteropatriarchy. The spectacle of the dismembered femme of color body is a commodity under patriarchy and white supremacy. The Asian femme body is a site of orientalism, an always already orientalized site. In All Things Lose Thousands of Times, how do you resist the spectacle but also celebrate the fragmentation? How do you stretch against it, fight that turn? How do you deflect consumption by haphazard spectators?

Peñaredondo: “To resist the spectacle but also celebrate the fragmentation,” as you so well put it, I feel is an evolving state of existence. It’s like all my identities merging at the entrance of a kind of wokeness. I identify as a queer, Pilipinx, cis-questioning, first-generation immigrant, artist woman of color, and as I openly state this, I’m aware of my position of privilege. I have access to the multiplicity of this language. I also have access to its choices, to its interwoven tissues, and the intersectionality weaved through them. As a person whose culture is enmeshed in histories of imperialism, colonization, machismo, and the fragmentation that comes with that, I accept that my world is full of contradictions and motley entanglements. Since poetry can be an expression of resistance and recovery, it has been a powerful, creative, and intimate vehicle in which I navigate through the thickets.

I’m in the process of finishing Zenju Earthlyn Manuel’s book, The Way of Tenderness: Awakening through Race, Sexuality, and Gender. Manuel is a Zen Buddhist priest. There are so many things this book unpacks for me when I think about fighting or deflecting microaggressions or haphazard spectators. She reveals not only dharma teachings that incorporate intersectional analysis but also personal stories about deep radical transformation through the practice of complete tenderness. During these high times of politics and injustices, I’m deeply stirred and influenced by her teachings of what tenderness means, especially as a queer person of color. Manuel expresses that liberated tenderness is a “way of lessening and finally removing the potency of our tragic past as sentient beings” as it will change what is “within us that leads us to annihilate the unacceptable difference between us.” But she also poses the question, “given the deep relationship between awakening and the body, why not explore the surfaces of this body — its race, sexuality, and gender — in relation to it awakening at its heart?”

Ravine: This “liberated tenderness” you write about in terms of Manuel’s book feels really important. It seems like a huge part of your social and artistic practice right now, to incorporate a liberated tenderness or grounded awakening. I think there is tenderness and grounding in how you resist and stretch and deflect through your incantatory spell-making, through tracing the scatter. In your poem “Aubade Cassette” there is “desertion,” “diagonal,” “diagram,” and “startling” in your pathways. In “Women and Children for Sale” you write about people who “calmly jaywalk / with confidence” scattered across exclamation points and catcalling and other multisensory collisions in what feels to me like a “Cyber Asian” night market. (Cyber Asia is a concept from Karen Tei Yamashita’s Anime Wong.) Your poem reminds me of when I went to Thailand for the first time and how that “return” didn’t feel as much like a return as my “return” to the US afterward felt like a turning. Like you say “will turn to a breached animal,” it was a folding in and discarding of new languages, items, scenes, street food. Mg Roberts writes in her beautiful foreword to your book that “bodily boundaries are muddled by notions of return,” and you write “when she turned around / the back of her neck / no longer a neck / but an extension of my arm.” In your poem “Return” you write: “I came back not to regret / or ask the particulars of why I left. / When a tree falls, its roots / aim jagged, pointing / in all directions.” This jagged pattern, this jagged kinesthetic, feels central to your work. You are “an expert in hinging.”

In your poem “Parts of the Body Before It Was the Body’s Pain,” you write:

from above, one is seeing

what is first gathered

then dissembled on the floor

that spirals to summation:

I come to your work from an aerial view, and so winged I see text and body scatter jagged and then spiral into summation. I feel “eager / for the pulpy bits of [my]self / moving, no longer cut in half / but some bandaged organism,” like an “extremity dancing / from each separation of the body” because of “this craving / for fierce / locomotion.”

Peñaredondo: Yes, there is a lot of truth in that. We both know poetry is birthed from prayer, meditation and oral storytelling. I find strength and refuge in those elements that poetry can embody. There is a kind of cleansing or clearing that happens when poetry enters incantation, and I like to think that space is both creative and sacred.

That “jagged kinesthetic” I feel reflects my personal take on queer postcolonial identity. It is never fixed or stagnant but always morphing or adapting to one’s current surroundings for survival, for perseverance, for reimagination in order to resist erasure. Furthermore, I deeply relate to what you said about being a tourist within one’s body, culture, and/or ethnicity. This state of displacement or disconnection is so significant among colonized and queer folks of color. At the same time, it is not a position of inferiority or scarcity (although it feels that way sometimes) but rather a position of abundance, richness, and intersectionality. Also, I strongly believe these positions hold the keys to radical healing and recovery. I’m so grateful we crossed paths.