From Bohemia to conceptual writing: Literary publishing and printing in California from 1890 to the present

by Johanna Drucker

On October 9, 2010, I convened a symposium at the William Andrews Clark Jr. Library, accompanied by a small book fair, that was designed to put a number of different communities together, even if only for a day: scholars, poets, publishers, artists, librarians, and graduate students in the MLIS program at UCLA. A part of the UCLA system, the Clark Library was established in the 1920s as a private collection that focused on 17th and 18th century literary and scientific works, late 19th and early 20th century fine press, British Arts and Crafts printing, and the work of Oscar Wilde. These strengths remain the core of the Clark’s holdings, and among them are an extensive collection of the work of the fine press community that developed in California in the early 20th century. Clark knew the figures in this community personally, and commissioned work from them for unique editions of classics for his library, such as a number of volumes designed for Clark in the 1920s by John Henry Nash, the San Francisco fine press printer. The deluxe approach appealed to Clark, and though not all the works in his collection conform to the same code of production values, the term “fine press” is defined by the use of handmade paper, handset type, and elegant bindings of large-sized volumes. The contents of these books are more often drawn from the classics than from the work of contemporary literary figures, and the symposium was meant to address (or redress) some of the tensions that have put fine press printing into dialogue with independent publishing, artists’ books, and other innovative, experimental, and conceptual works over the last century.

The UCLA librarians who became the stewards and curators of Clark’s collection also knew the small circle of Southern California printers who saw themselves as the direct continuation of the fine press tradition. Ward Ritchie, a charismatic figure in the circle of Los Angeles printing, first learned to use a press at the Grabhorns. Nash’s slightly younger contemporaries, Edwin and Robert Grabhorn, assisted by Robert’s wife Jane, were known for their generosity and mentorship, and through their informal apprenticeships trained another generation. Their tastes were middle-brow and eclectic, and remote from the radical work of Futurism, Dada, or other major modern movements shaping print and poetic aesthetics in Paris, Milan, London, and New York at the time. Adrian Wilson, also acquired printing skills and design knowledge in the Grabhorn shop in the mid-1940s. Wilson, and his wife Joyce, had strong connections to the theater, where the modern texts of Ionesco, Beckett, and others were among the repertoire. But modernism was an import, not an export, for the California literary scene until Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s founding of City Lights in 1953 put San Francisco on the map as a site of innovative beat publication.

Lawrence Clark Powell, Ritchie’s childhood friend from Pasadena, became a scholar and librarian, writing on the work of Robinson Jeffers, a poet whose hand-made stone house on the California coast and proto-eco sensibilities marked him as an idiosyncratic figure in American modernism, but one with a national profile that the local culture could claim as its own. Powell’s personal connections and professional interests left their mark on UCLA’s libraries (including one that bears his name) and the traditional tone of his literary and aesthetic tastes seemed suited to carry on Clark’s legacy. The codes of material production, rather than literary credentials, have tended to be the criteria on which the collections have been built. The rich history of literary life in California, particularly from the 1950s onward, is barely represented in fine press publishing, and the symposium and fair were meant to suggest that this dimension of cultural history might usefully be brought into the Clark’s purview. The collecting of artists’ books is a more recent development, though in my opinion, very few artists’ books are in active dialogue with either the literary or art mainstream, and their isolation from trends of critical aesthetic activity makes them a kind of intellectual backwater. The observation does not hold universally—but among the many artists who make books, only a handful have a reputation outside this limited community. While we might say the same of the literary figures in conceptual writing or experimental poetics, the critical, scholarly, and academic interests in their work broaden the audience and circulation networks beyond the precious realm of special collections’ vaults. Contemporary fine press creates a trade in fine leather, exquisite binding, and concentrated production value for a luxury market, rarely one that troubles its consumers with writing from the world we live in. Material codes signal the class lines of taste, in classic demonstration of Pierre Bourdieu’s sociological parameters, and the contents of the books across these various categories in the spectrum of fine press, artists’ books, small press, and independent publishing conform to similarly distinct domains. So my project was to suggest more synthesis, more dialogue, more cross-pollination. Even for insiders, the tasks of judging the relative merits of different strains of contemporary writing are difficult, and charged with politics of a scene and its players. Would Clark’s literary and aesthetic tastes have evolved? After all, he brought Merle Armitage to the LA Symphony, and appreciated the designs of Alvin Lustig, two of the most advanced graphic designers in America at the time.

The holdings at the Clark contain archival resources as well as fine press books. Together these offer insight into the way fine press publishing served as one instrument for community formation and creation of identity for Los Angeles, particularly, at a time when the region was emerging as a cultural center. Ritchie’s studio was situated at one point near to the Disney studios, and hard as it may be to reconcile the esoteric world of fine press with the burgeoning industry of film and fantasy, Ritchie’s archives contain evidence of direct connection in the form of the publication titled Mousetrap, with its irreverent humor and mocking tone. At another extreme, accounts of the young John Cage, a fellow Pasadena resident, pounding away at a piano in the corner of Ritchie’s shop while the presses are running, intriguingly points to an encounter with another, very different, dimension of contemporary art. Suspended between industrial production and radical avant-gardes, though partaking very little of either, the fine press tradition made a local contribution to the varied strands that comprised mid-twentieth century California.

Printing arrived in California in the 1830s with the Spanish governors when Agustin Zamorano set up a press in Monterey to print political tracts and government documents. Utilitarian printing of all kinds supported the boosterism essential to a growing economic region. Newspapers in Spanish and English, some in bilingual editions, as well as the usual job-shop fare of public notices, business forms, commercial advertising and other ephemera proliferated in the 19th century. The first work claimed by afficiandos of fine print, Edward Bosqui’s 1877 Grapes and Grape Vines of California, was produced under the auspices of the California State Vinicultural Association. Beautifully printed and illustrated, it detailed regional agricultural bounty with lush and sensuously colored images.

In the 1890s a small band of imaginative pranksters in San Francisco helped create a spirited, if belated, Bohemian literary movement. Calling themselves “Les Jeunes,” the group around Gelett Burgess produced witty and often irreverent imitations of works by well-known figures such as Aubrey Beardsley in England or Will Bradley in America. They addressed their publications to a literary audience that was au courant or “in the swim,” to use the language of the day. Their pages were filled with in-jokes that depended on current trendy references. Though Bohemianism was already a nearly defunct cultural trend by the 1890s, Burgess was a wit who made his living writing popular humor. The literary journal, The Lark, was shortlived but lively, and part of a large international trend in which small magazines fostered modern poetry, prose, and critical exchange within the social media of their day. If Burgess was quintessentially middle-brow, so was Nash, though his pretenses and aspirations were towards Brahmin status. He began printing in San Francisco in the 1900s, his aspirations were to emulate the work of William Morris and Thomas Cobden-Sanderson and their conception of the “ideal book.” Printing in the mode in which he practiced was an art, he asserted, not a trade, and the volumes were prized by a wealthy clientele who perceived the elegant bindings and exquisite press work as markers of cultivated taste. Designed with type fonts and page proportions copied from the great humanist printers of the Renaissance, his productions showed their allegiance to venerable bookmaking traditions by reproducing texts of canonical writers.

Book design and small press publishing in Los Angeles might have followed the same path of humanistic revival that had formed Nash’s taste had Ritchie not been gone to Paris to pursue training with the remarkable printmaker, François-Louis Schmied. Ritchie absorbed lessons about modern book design that were more recent than the Arts and Crafts artists notion of the ideal book, but still remote from the avant-garde. A number of exceptional artists helped shape a regional aesthetic. Valenti Angelo, Paul Landacre, Mallett Dean, and Mary Fabilli worked within the conventions of figurative and landscape traditions, but in a modern idiom. Literary tastes in the fine press world stayed close to the mainstream, while engagement with book form and formats kept to a book-club sensibility meant to appeal to a subscription list. Robert Louis Stevenson and Edgar Allen Poe, not D.H. Lawrence, James Joyce, or the Bloomsbury crowd—let alone André Breton, Tristan Tzara, or Wyndham Lewis—were the authors whose texts populated the lists of books boasting hand-set type and printed end-sheets.

Through the 1950s and 60s, beat poetry and pop art became major cultural movements with strong communities in San Francisco and Los Angeles. The publications they spawned were distinct in character from those of the fine press. Slim chapbooks and the ubiquitous broadsides printed letterpress flourished alongside a growing number of self-published projects using mimeo machines, or the local copy shop. When Ed Ruscha published Twenty-six Gasoline Stations in 1963, he could not have realized that the small offset-printed book would come to be seen as the founding instance of artists’ books in the conceptual vein. Traditions of hand composition and fine presswork remained constant through the 1960s and 1970s, most often linked to conventional literary values, but the underground press and alternative publishing flourished from the 1960s onward. The graphic designs and aesthetic sensibilities of feminist works, activist journals, underground comix, and the street press (tabloids, newspapers given away for free on the street) diversified the range of writers in print.

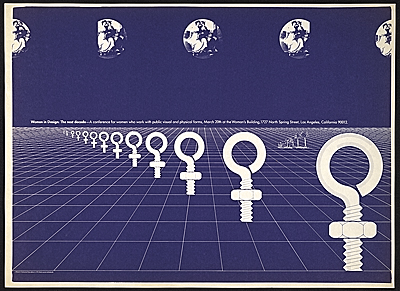

The creation of a print shop at the Woman’s Building in Los Angeles in 1973 had national repercussions. A few years later, in 1975, the West Coast Print Center was established in the Bay Area to provide low cost printing services for the literary community. Its offset presses and photographic darkroom, platemakers and light tables, were industrial, not craft, equipment. Language poetry flourished, along with procedural writing and conceptual work in the experimental tradition. A steady stream of chapbooks, magazines, and small press publications gave evidence of the vitality of literary activity that connected the Bay Area art, literary, and performance scenes to those of Southern California (Beyond Baroque and other sites) as well as to a national network of activities in New York’s alternative spaces (Franklin Furnace, The Kitchen, Printed Matter) and beyond. Many literary presses came, went, or endured, from the 1960s onward including Black Sparrow, Tuumba, Turtle Island, Sun and Moon, Oyez, and others that sustained the literary scene through their varied printing activities. Well-made books, meant to serve as respectful presentations of work their editor-publishers deemed important enough to bring to the public, the volumes of these publishers reflected the vibrant literary life in many communities across California. A full history of this publishing history and its impact on larger cultural spheres has yet to be written, but if and when it is, the faultlines that divide the strata of publishing activity will be markedly clear.

All of these strains of activity continue. The legacies of aesthetic positions imprint themselves, taken up by each generation, and sometimes questioned, sometimes not, sometimes engaged with self-consciousness and other times merely imitated, like manners, in order create work that looks just like its author/publishers think it should. Thinking a book or publication and bringing it into being is always an argument for what a book is, could be, and how it works and circulates in the media and aesthetic ecologies of its conception. My own aspiration is to see more dialogue with vital poetics in the production of books to come, and less adherence to codes of production for their own sake or marketing purposes. More concept, less product—the statement is not a prohibition against fine work, elegant design, or engagement with traditions of printmaking, photography, aesthetic traditions of all kinds, but it is a caveat against mistaking form for content in the valuation of a work, and for taking seriously the literary dimensions of work curated and collected. The formal innovations that artists bring to books, and the commitment to the craft of production that are central to fine press publishing, both have a role to play in the creation of innovative literary works, but most likely these will arise through partnerships, and not in isolation. I don’t know if anyone left the symposium that day with a sense of new possibilities, or merely left with a reinforced sense of justification of their own position, but at the very least, the chance for the students to see the range of work being produced and to participate in its discussion and recognition provided an opportunity, all to rare in graduate school, to have a direct connection to ongoing artistic and literary activity.

A Primer