Sited

On Jenny Xie and the fate of the flâneur

Perceptual distance may turn into mental distance,

and the phenomenon of disinterested beholding may emerge,

this essential ingredient in what we call “objectivity” — Hans Jonas[1]

How can we untangle the braid of sight, language, and power that structures our contemporary world? Sight, regarded as the noblest sense, at least since Plato, continues to dominate our sensory orders and technologies. Travel, cinema, media conglomerates, Instagram, the scientific method. It’s not controversial for Jonas (among others) to claim that “the mind has gone where vision pointed.”[2] But whose vision are we talking about? To whose detriment does it gaze? These questions and their subsequent critiques aren’t new.[3] To gloss them here would embarrass their nuance. Still, let me hang the minimal scrim for what’s to come.

It’s 1967, and Guy Debord, grumpy but prescient, senses a change in the air. Throughout his treatise The Society of the Spectacle, he attempts to show how mass media and late-capitalist modes of production degrade social relations. Together, they reorient human organization around images detached from lived reality. Their slogan: “What appears is good; what is good appears.”[4] For Debord, the more these images mediate social activity and perception, the more they obscure systemic conditions of exploitation. And the more these “fragmented views” congeal into a “pseudo-world,” the less an individual viewer possesses a sense of here and now.[5] That is, by “eliminating geographical distance” through the immediacy of spectacle, “this society produces a new internal distance in the form of spectacular separation.”[6] Neither collective nor individual bodies are immune to this subtle inversion, a “culmination of humanity’s internal separation.”[7] And the eye, fantastic aperture, lets spectacle in.

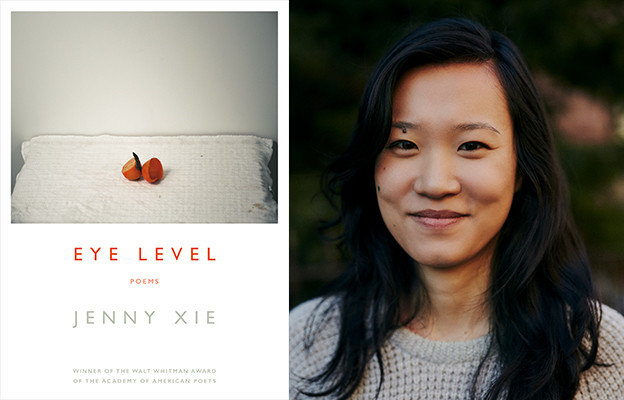

Fifty years have passed, and while Jenny Xie hasn’t answered Debord’s anxiety directly, she’s doubled down on his point. “Nothing is as far as here,” she writes in the final line of Eye Level, her debut collection of poems.[8] Her conclusion marks a point of departure, not a place to rest. In a present tense with globalized spaces, distance beguiles the traveling eye. Images on Google Maps precede the terrain we actually experience. Meanwhile, notions of “here, now” belie a sense of displacement issued by devices ranging from livestream to the Oculus Rift. Bundling these trends together, something strange is happening. That is, it seems our approach to a shared reality has been vexed, if not compromised, by vision and its instruments. Worse, in an ocularcentric world, some stand to benefit from its sensory hierarchy more than others — subjects entitled to see without being seen, to gaze from a stable position of power.

Xie, gracefully observant, turns to the lyric in order to trouble our pact with the visible world. Meanwhile, I turn to Xie in order to trouble visuality in general. Reading Eye Level provides no easy answers about our ways of seeing. It does, however, teach us to keep “circling” (49). It helps us perpetually retrace the assumptions bounding an ethics of sight. And it points to fluid conditions in selfhood that complicate how one sees — conditions that, for Xie, include (but aren’t limited to) being a traveler, woman of color, artist, and immigrant daughter all at once.

Leaping into Xie’s circuit, I want to juxtapose her lyric thinking with a figure that reflects and refracts a dominant way of seeing in Western modernity: the flâneur. Pitting these forces will, I hope, reveal how vision intersects with race, gender, and language, often to oppressive results. Above all, I want to think with Eye Level about who gets to see and how in a world where insight rarely surfaces. It lurks much lower in the blind spot.[9]

***

Why the flâneur, that dandy of fin de siècle Paris? A sightseer and emblem of urban life, the figure clings to contemporary cultural theory and literary lore alike.[10] Its emphasis on aimless wandering often casts the flâneur in a heroic light — a nonconformist, an artist in bloom. Too, these same qualities can be used to problematize his status as privileged voyeur. In this sense, shadows of flânerie fall across a century of thought on perception, identity, fetishism, and public space. By extension, I’d argue such a figure haunts the itinerant poems in Eye Level.

I first encountered the flâneur in Baudelaire’s street scenes, but I know him best by way of Walter Benjamin’s writings on nineteenth-century Parisian life.[11] Almost always white and male, he’s a man of the crowd while standing apart from it — a “physiologue,” a strange amalgam of poet and ragpicker.[12] Observing a panorama of commodities and urban commotion, he abandons himself to imagery’s pull, drunk on surfaces of splendor, and waits to reflect on their power until he’s back in the shadowy garret. As Benjamin says in The Arcades Project, “The crowd is the veil through which the familiar city is transformed for the flâneur into phantasmagoria.”[13] In other words, the people and places he encounters are at his disposal: seemingly rife with transcendent potential, floating free of bourgeois trappings.

Sarah Anjum Bari is right to highlight Benjamin’s use of “phantasmagoria,” which recurs throughout his writings on flânerie. Derived from the French “fantasme,” it’s also the name of a famous London exhibition from 1801. In it, magic lanterns made optical illusions, dazzling viewers unacquainted with their underlying tricks.[14] What interests me is how the flâneur consumes a similar array of spectacles, a parasite on the “separation perfected” by commercial life. What concerns me is how his “disinterested beholding,” to echo Jonas, came to correlate with reasonable thought, which thereby extends to knowledge generation.[15] Beauty may lie in the eye of the beholder, but why should the flâneur be given a premium on truth claims, too?

I shudder to see these traits described as touchstones of the “modern artist-poet.”[16] Less common, but still evident, is praise for his cosmopolitan wanderlust.[17] What’s often overlooked is how the flâneur, entitled to stroll without marks of Otherness, can become Nobody: less like Dickinson’s shadow self, more like frat boy abroad.

This, rightfully, is why the gendered parameters of flânerie have been contested. The flâneur was written by and for men, permitting a minor cadre to access some essence of the modern and make it new. In light of this, critics have questioned how women and genderqueer people can become flâneurs, too. For them, navigating public space is routinely subject to harassment and fear. How might they enter that coveted state of absorption, that with-and-apart, when their presence is rendered hypervisible by others? Janet Wolff asserts that even the possibility of founding a flâneuse is futile: “such a [nonmale] character was rendered impossible by the sexual divisions of the nineteenth century,” then further obscured by modernist phallocentrism.[18] In this sense, the flâneur only props a masculine master narrative. We’re better off, as The New Republic recently argued, killing the figure and investing attention in radical forms of empathy.[19]

Another avenue has been taken. Writers like Lauren Elkin have tried to expose an alternate dimension of flânerie, one that incorporates histories of women walking, writing, and shaping the cities they loved.[20] From Virginia Woolf to Sophie Calle, real flâneuses worked and thrived beyond any label bestowed by the gatekeepers of lit-crit. I think of the titular character in Agnès Varda’s Cleo from 5 to 7, a singer roaming Paris by twilight. Men in passing rubberneck Cleo. Varda’s camera makes vicious cuts from glare to glare, a montage of gawking. Nevertheless, she persists. For every film in the French New Wave extolling the exploits of aimless men, Varda reminds us that people like Cleo have paved their way toward visibility that, while far from undisturbed, is situated more on their terms.

If we walk to the end of this thought, flânerie needn’t disappear outright. It could still afford a “critical metaphor for the characteristic perspective of the modern artist,” as Deborah L. Parsons argues.[21] But metaphor has little bearing on praxis. The framework would need a substantial software update, something to open the code to pluralities that have come and have yet to come.

What neither approach has addressed is the very mechanism by which all flânerie notes, absorbs, and thereby attains: the eye, rapacious and probing, screened by distance. To thoroughly challenge flânerie means squaring off with sight and its ramifications. What kind of visual politics play out here? How does the gaze of contemporary travelers, writers, expats, Snapchat stars, and culture cronies regulate and command the sensible? Can a young, Chinese American woman touring Cambodia partake in the flâneur’s breezy leisure? Or do we need to practice new ways of seeing altogether?

If the flâneur is a receptacle in which stimuli becomes knowledge, Xie turns the figure upside-down to deconstruct its sensory devices. In this way, Eye Level confronts the ethical dimensions of what and how a body sees. What’s at stake is the eye’s revision. What’s at stake is the constitution of sight that guards against its own potential for violence, its power to draw and enforce borders containing identity, language, and nations. To ask “Who gets to be a flâneur?” and “Who gets to see as a flâneur sees?” pries apart the heart of power. What pours out? For Xie, “So much interior / unpicked over by eyes” (76).

***

In an interview with BOMB, Xie observes how “travel, imaginative or physical, can sharpen perception and forcea measuring of distance and difference.”[22] Displacement and the ethical concerns it raises are, for her, “conducive to examination, interrogation, reordering.” Through its varied geographies, Eye Level dramatizes these visual collisions in global spaces. An emphasis falls on what we see while in motion and how that seeing orders contingent (and exhausting) relationships between subjects and objects — the self, of course, bounced from one to other at random. It’s why Xie introduces the book with an epigraph from Antonio Machado: “The eye you see / is not an eye because you see it; / it is an eye because it sees you” (i).

Machado’s maxim identifies an immediate rift in the flâneur and Xie’s speakers. The eye of the flâneur — seeing without being seen — assumes a stable “I” while producing a hypervisible “them.” His sight has been socially permitted to render bodies in passing as Other, as reified images. Meanwhile, Xie’s speakers struggle to navigate public spaces with the same degree of abandon. Indeed, they can’t even circumvent constant self-scrutiny: “I’ve gotten to where I am by dint of my poor eyesight / my overreactive motion sickness” (13), as if a marionette pulled by accidents of perception. A problem asserts itself already: the physiognomic is political, yet to be a flâneur, one must always already stand outside the (bio)political.

This problem — playing out across Hanoi, Phnom Penh, Corfu, and New York City’s Chinatown — forces Xie’s speakers to double over in doubt. Given their multinational, -ethnic, and -linguistic ties, a state of belonging is always suspended, absorption routinely disrupted. How can these speakers satiate an “appetite for elsewhere” (16) when power dynamics reappear everywhere, whenever they “reach” with “the outsider’s extravagant need” (5)?

These dynamics are given flesh and blood in “Phnom Penh Diptych,” the book’s most critical (yet never didactic) reflection on race, vision, and distance. Cycling through the rinse-repeat of wet and dry seasons, the speaker narrates a perceptual journey through Cambodia’s changing landscape. Its cities are saturated with “new money lapping the streets” and “shells of high rises.” “How do eyes and ears keep pace?” she asks (7). It’s hard to observe any nuance when capital razes colonial history and puts up a parking lot in its place. And yet it’s impossible for Xie not to notice the billboard for whitening face lotion — a kind of colorism from above.

Contra flânerie, Xie’s speakers acknowledge that travel’s beauty is always “suspect” (12). Scars can be traced despite “low visibility” (10). The ideological project of modernization attempts a total, synchronous makeover, but cracks emerge if you know where to look. Xie certainly does. Her speakers hone a double vision sharp enough to parse through gilded surfaces. Yet doubling comes with a cost: the disruption of absorption necessary for flânerie.

This frustrating dialectic further unfurls on a tour of the Killing Fields. Neither tourist nor native, Xie’s speaker has little choice but to stare in the face of historical trauma. She measures its residue on the present while fellow riders enjoy the view:

The tourists curate vacation stories,

days summed up in a few lines. […]

How the viewfinder slices the horizon —

Their pleasure is shrill, I agree.

It knows little of how banality

accrues with no visible evidence. (12)

Later, Xie includes a cameo from “Sambo the elephant,” who nonchalantly congests local traffic. The image, part and parcel with Orientalist fantasy, exacerbates the pain of this scene. The elephant charms, the tourists shoot, and history slips away unnoticed. Meanwhile, the banality of evil — whether Kissinger or the Khmer Rouge — sneaks beneath the vista. That Xie enlists a caesura to cut the word “horizon” further brutalizes the page. It signals which segments of historical memory a tourist — or a flâneur — are privileged enough to blink away.

The speaker’s absorption gets further disturbed by the rigidity of binary forms — in particular, the constructed clash between East and West. In the latter half of the “Diptych,” the speaker, seated in a Chinese restaurant, is asked by the owner to fix their menu’s English. “I translate what little I can, it’s embarrassing,” she says. A server then chimes in: “Just passing through?” The speaker may visibly pass as Chinese; she may fondly associate fellow diners with “uncles on both sides of my family” (14). Even so, she fails their expectations. She is made to be ashamed. Under the aegis of casual surveillance, intersectional identity suffers regulation.

What Xie ultimately illustrates in the “Diptych” and beyond is twofold: a phenomenological account of travel through formerly colonized spaces, and a measurement of ethical distortions tied up with that travel. Given Xie’s sensitivity to place, this complex process distills into moments of sly, Imagist precision. As seen from Greece in a poem called “Fortified,”

On the bus ride back,

we pass a store named Ni Hao, selling pelts.

Hello in all directions. (21)

The effect of these lines is stunning. Space, strung together by shops and “white sailboats of the rich,” dissolves into spacelessness. Signs and symbols twist into halcyon fantasy; capital is its lingua franca. Again the speaker finds herself displaced from sight’s smooth operation, but this time, it’s not entirely unpleasant. In fact, her witness brims with wonder. Not only do these lines condense a certain ethos of Xie’s poetics, but they reveal, however briefly, a more benevolent mode of sight: one that’s destabilized, open, conscious of context, and always in pursuit of arrival.

A glimpse like this suggests that sight isn’t always reducible to ethnographic violence. With care, it can be marvelous, after all. But building an ethical world-vision requires more than a glimpse. Whatever one might appreciate in the flâneur’s gaze, however innocent it may scan, it can’t be disentangled from its exclusive and ahistorical imaginary. The uncritical eye is always complicit. We all deserve better. I return to a line from the book’s first poem, “Rootless”: “Me? I’m just here in my traveler’s clothes, trying on each passing town for size” (1). Xie’s speaker may be trying on the flâneur’s attire, but over and over it proves an ill-fitting cut. It’s fashioned for somebody else’s look.

***

The flâneur’s eye is not an eye capable of gauging difference. It can’t even see the singular as something contingent, something unstable. Perhaps that’s due in part to a faulty formula whereby I = eye, a flattening of the interplay between body and mind.[23] Eye Level, however, knows the self is a fiction. As Xie goes on to say in BOMB, “So much of everyday living involves performance, exposure, and projecting a solidity of self.” In turn, many of her poems “seek to dismantle the false binary of interior/exterior, and of the interior as some sort of gated enclosure.”[24] Sight that sees itself would discover ceaseless circulation — from the social world and its affects to the body’s reactions. Sight that’s blind to these conditions furthers the worst effects of flânerie.

In this way, Eye Level tracks how a subject comes to regard her identity as process rather than product, a journey indebted to a wider and wilder use of the whole sensorium. This is no small feat. As she writes in “Epistle,”

the root of this self-denial is long

all those years I was spared seeing myself through myself

Now the stifling days disrobe

distance giving autonomy the arid space to grow (22)

Over time, Xie learns to seed the excluded middle — “gap gardening,” to steal a phrase from Rosemarie Waldrop. As stimuli are brought to bear on the traveler, zones within the interior sprawl, shrivel, and are transformed. “One self prunes violently / At all the others / Thinking she’s the gardener,” says Xie in “Tending” (58). Elsewhere, in “Melancholia,” a simple gesture like petting a dog, catching the “elemental” odor in its mouth, sends the speaker spinning through her life “slow and fast, fast and slow” (52). In these poems and elsewhere, polyvocality and ample white space are charged with indeterminacy. They mark a call and response from minds within minds, challenging received impressions and delaying certainty. Insofar as certainty can never be fixed for an intersectional subject, gaps are actually the goal. They produce not lack but inquiry.

I’m in a hurry to call this openness a sustainable way of seeing. Not just for its skepticism of the visual, but for how it levels all five senses into a synthetic (and synesthetic) organization. When Xie detects “the smell of my lateral gazing” (5), it’s not just poetic flourish: she signals heightened attention thanks to a fluid deployment of all the body’s resources. She knows perception can only cohere through its irresolvable differences. And when knowledge is eventually assembled out of impressions, it makes no claims on objectivity: negotiations are always in play. If the senses can be so democratized, and if the subject can be so destabilized, separations in the social aren’t so settled after all.

But perhaps it’s enough to say this: Eye Level illustrates that the borders are porous. To acknowledge this, minding their paradoxes and contradictions, decentralizes the power of sight. It means, in our own spectacular time, we can walk and write our way toward a sensitive appraisal of the visible, the invisible, and the continuum between.

***

A lingering thought: at the start of “Margins,” Xie describes “water striders on a pond’s surface, / light as calipers” (67). Quiet as the diction is, this line gives me pause. I think about how water comprises most of our circulatory systems, flowing between the human and planetary body alike. By contrast, a caliper, an instrument for measuring the internal diameter of objects, can’t possibly pronounce what’s inside forces that flow. It can’t even locate firm edges to grip. I wonder, then, about the accuracy of our instruments, especially the eye. Uncritical faith in its reach, in the knowledge we believe it brings, delivers us into the flâneur’s trap. It may be that to measure what’s abstract but substantial — distance, difference, selfhood — we must admit enigma. There is wonder in the play of light upon the rippled surface, and there is wonder in the nameless shapes below, water growing out of water.

1. Hans Jonas, The Phenomenon of Life: Toward a Philosophical Biology (New York: Harper & Row, 1966), 151–52.

2. Jonas, 152.

3. See Martin Jay, Downcast Eyes (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993).

4. Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle, trans. Ken Knabb (The Bureau of Public Secrets, 2014), 4.

5. Debord, 2.

6. Debord, 90.

7. Debord, 7.

8. Jenny Xie, Eye Level (Minneapolis: Graywolf Press, 2018), 76.

9. It’s worth pausing for a moment to trouble the “blind spot.” Such a phrase, when referring to the scotoma found in every mammalian eye, is a useful analytical tool. It can humble us to account for what’s unknown, overlooked, and underestimated in our field of vision. Indeed, Paul de Man rode this metaphor as far as it would take him. At the same time, the blind spot is charged with ableist implications. Having a fraction of vision myself, I’m sensitive to the ease and indifference with which metaphors of illness are deployed as if they were unilaterally harmful rather than sites of possibility. All to say I’m uncertain how to reconcile these two feelings in me, but I’m inviting readers to help me sort them out.

10. See Martina Lauster, “Walter Benjamin’s Myth of ‘The Flâneur,’” Modern Language Review 102, no. 1 (January 2007): 139–56. Her argument against Benjamin’s depiction and its consequences is fascinating in its own right. I don’t take issue with her claims here. Instead, I take the flâneur as a culturally ingrained concept with which we must grapple, myths and all, if we are to relax its hold on the urban imaginary.

11. See Walter Benjamin, “The Flâneur” in Charles Baudelaire: A Lyric Poet in the Era of High Capitalism (Brooklyn, NY: Verso, 1997), 35–66.

12. Benjamin, “The Flâneur,” 35.

13. Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999), 21.

14. Sarah Anjum Bari, “Visiting Sephora with Walter Benjamin,” Electric Literature,May 27, 2018.

15. So much has been written about the assault on Enlightenment principles that it’s impossible to entertain a discussion of it here. Even so, I’d like to gesture toward an idea raised by Lyn Hejinian: “The notion of ‘myopia’ is linked to perception and replicability; western science bases its definitions of knowledge on certainties, and certainty requires that something be perceivable repeatedly.” Insofar as the flâneur is privileged to walk, perceive, process, and disseminate those percepts, he’s given the keys to a transcendental, ahistorical certainty. By extension, sensory deprivation or other kinds of perceived deficiency can lock one out of this regime of truth. See Lyn Hejinian, “Roughly Shaped: an interview with Lyn Hejinian by Craig Dworkin,” Idiom no. 3,(1995).

16. See Gregory Shaya, “The Flâneur, the Badaud, and the Making of a Mass Public in France, circa 1860–1910,” The American Historical Review 109, no. 1 (February 2004): 41–77. Also note how Benjamin chooses to encapsulate the flâneur and his fetishes in a quote from Baudelaire’s Paris Spleen: “The poet enjoys the incomparable privilege of being himself and someone else as he sees fit. Like a roving soul in search of a body, he enters another person whenever he wishes. For him alone, all is open; if certain places seem closed to him, it is because in his view they are not worth inspecting.” By now this sentiment, I fear, has lodged itself in far too many discourses around artistic license. See Benjamin, “Charles Baudelaire: A Lyric Poet in the Era of High Capitalism,” 55.

17. See Bijan Stephen, “In Praise of the Flâneur,” The Paris Review, October 17, 2013, and Jens Hoffmann, “The Return of the Flâneur,” an exhibition essay for The Arcades: Contemporary Art and Walter Benjamin, The Jewish Museum, 2017.

18. Janet Wolff, Feminine Sentences: Essays on Women and Culture (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990), 47.

19. Josephine Livingstone and Lovia Gyarkye, “Death to the Flâneur,” The New Republic, March 27, 2017.

20. See Lauren Elkin, Flaneuse: Women Walk the City in Paris, New York, Tokyo, Venice, and London (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2017).

21. Deborah L. Parsons, Streetwalking the Metropolis: Women, the City, and Modernity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 5.

22. Jenny Xie, interview by Mariam Rahmani, “The Self Is a Fiction: Jenny Xie Interviewed by Mariam Rahmani,” BOMB, April 12, 2018.

23. By this I mean to suggest that the flâneur is guilty of more than objectifying the exterior world. Indeed, his original sin might be a failure to appreciate the indefinite and indeterminable exchanges between inner and outer worlds, between a body’s effects and affects alike. Or, in Xie’s words, “To be profligate in taking in the outer world is to shortchange the interior one.” Xie, Eye Level, 46.