The activist flâneur

Last weekend (October 25 & 26) was the occasion of the fifth annual Creative Time Summit in New York City. Creative Time is an organization known for producing public art projects, but recently it has become an important producer of conversations about the intersections of art and social justice. This year’s Summit was titled, “Art, Place & Dislocation in the 21st Century City.” Speakers included Rebecca Solnit, Lucy Lippard, John Fetterman (mayor of Braddock, PA), Rick Lowe (of Project Row Houses), Lucy Orta, Laurie Jo Reyolds, and many others. Panels addressed gentrification, sustainability, and grassroots resistance to urban development (all talks are available online).

One of the panels was called “Flâneurs.” The Situationist psychogeographer is often discussed in relation to the 19th century flâneur. Taking his cues from Edgar Allan Poe, Baudelaire described, the flâneur as “a man of the crowd”:

“The crowd is his element as the air is that of birds and water of fishes. His passion and his profession are to become one flesh with the crowd. For the perfect flâneur, for the passionate spectator, it is an immense joy to set up house in the heart of the multitude, amid the ebb and flow of movement, in the midst of the fugitive and the infinite. To be away from home and yet to feel oneself everywhere at home; to see the world, to be at the center of the world, and yet to remain hidden from the world….He is an ‘I’ with an insatiable appetite for the ‘non-I’…”

At the panel on flâneurs, Vito Acconci said he had reservations about the term because it carried connotations of a passive person: an idler or a dawdler. He said that he was much more comfortable with the idea of the flâneur as “an activist, an instigator, somebody who causes trouble.”

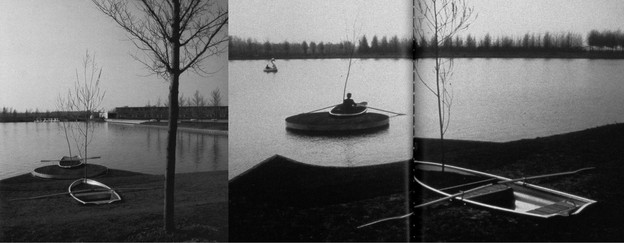

Acconci then stated his belief that architecture has to move, otherwise people are subjected to it. The activist flâneur is thus someone whose walks can activate and change the environment. An example he gave was a project from the 1990s called “Personal Island” (see image above), where a boat is locked into the land as if it were water, and the rower can row her island out to sea.

Acconci made a point of explaining how he had no art or architecture training, but rather was the product of the Iowa Writers Workshop. He said “my stuff comes from words and since it comes from words, it comes from concepts.”

The concept of the “activist flâneur” has me thinking of a number of poetry projects that begin with walking. And although these walks might not cause trouble in the same way that a detachable island might, they do upset static notions of a place. For example, Kaia Sand's walk through downtown Portland, Oregon in Remember to Wave reveals that the site of a present-day roller derby was also the site of a Japanese internment camp during World War II. On a walk down “Dole Street” in Honolulu, Juliana Spahr reveals evidence of colonialism in seemingly neutral street signs and similarly bland public sculptures. On a walk through New York City’s Bowery, Brenda Coultas lists objects found in dumpsters or left at the curb in order to record a past that is being actively discarded in the face of wild real estate development. These poems ask us to bring “passionate spectatorship” toward a stance of critique.

Although Acconci stated his interest in a mobile architecture that empowers users, he also noted that flexible architecture can sometimes have the opposite effect. For example, “Courtyard in the Wind,” designed by Acconci Studio and built in Munich, Germany creates a kind of motorized turntable on the ground that’s powered by a wind turbine at the top of a nearby tower. As Acconci describes it, you could be having a conversation with a friend, sneeze, and then find yourself seven feet further around the circle depending on the wind. In this case the speaker/walker is at the mercy of the elements. Such a scenario reminds me of David Buuck’s Buried Treasure Island— particularly the moment when Buuck suggests that as part of his investigation of this former site of world’s fairs and military installations, he will ingest the toxins that saturate the landscape. He writes:

Although Acconci stated his interest in a mobile architecture that empowers users, he also noted that flexible architecture can sometimes have the opposite effect. For example, “Courtyard in the Wind,” designed by Acconci Studio and built in Munich, Germany creates a kind of motorized turntable on the ground that’s powered by a wind turbine at the top of a nearby tower. As Acconci describes it, you could be having a conversation with a friend, sneeze, and then find yourself seven feet further around the circle depending on the wind. In this case the speaker/walker is at the mercy of the elements. Such a scenario reminds me of David Buuck’s Buried Treasure Island— particularly the moment when Buuck suggests that as part of his investigation of this former site of world’s fairs and military installations, he will ingest the toxins that saturate the landscape. He writes:

“Practitioners using psychogeography and counter-tourism can visit and leave, often taking the ‘art’ while leaving the conditions unchanged. For BARGE [The Bay Area Research Group in Enviro-Aesthetics], this has necessitated the consumption of the poisoned land itself into my body and bloodstream, the lungs and the eyes, if only as a small gesture of solidarity and tactical magic. If we are to take in the treasures, we must likewise taste of the fever…”

Psychogeographies