Provenance report

William Carlos Williams's 1942 reading for the NCTE

The earliest known recording of William Carlos Williams reading his work was created on January 9, 1942, as part of a collaboration with the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) and Columbia University Press. The recording is currently available at PennSound, the largest collection of poetry recordings on the web, which is based at the University of Pennsylvania and directed by Al Filreis and Charles Bernstein. Beyond a limited amount of metadata, not much is known about the context of this recording. What was the NCTE’s intent for making the recording — preservation, access, or something else? Who was its intended audience? What kind of recording device was used to make it? Where, exactly, did the recording take place? Who recorded Williams reading?

With the guidance of Al Filreis, I recently learned more about the recording’s provenance by obtaining some of Williams’s correspondence with Columbia and the NCTE from Yale’s Beinecke Rare Books and Manuscript Library. We learned that the NCTE recording of Williams is part of its Contemporary Poetry Series collection of recordings and was intended for pedagogical use. These recordings were meant to be distributed to “students, and other lovers of literature,”[1] so that listeners would have the opportunity to glean additional meaning by hearing the authors of the poems perform them. The pedagogical significance of the Contemporary Poetry Series is that it marks one of the earliest cases of the use of technology and poetics pedagogy: the concept that a phonotext provides unique insight into a poem. The Contemporary Poetry Series anticipates the pedagogical project of PennSound.

On April 19, 1940, William Cabell Greet, a lexicologist and professor of English at Columbia’s Barnard College, wrote to Williams to invite the poet to lunch with him and two of his colleagues, Dr. George Hibbitt and Dr. Henry Wells. The letter suggests that they have lunch at the Columbia Faculty Club and, at some point that day, record Williams reading his poetry.[2]We don’t have further correspondence on the topic, but we do know that the recording actually took place about a year and nine months later, on January 9, 1942.

Ten months after the recording was made, on November 14, 1942, Williams was sent a letter by W. Wilbur Hatfield, the then-secretary-treasurer of the National Council of Teachers of English.[3] Hatfield thanks Williams for taking the time to make the recording and reveals some of the intent when he declares, “We are glad to have been instrumental in the preservation of the reading, and we think schools will be glad to have them now.”[4] It seems that the NCTE’s intention for the recording was twofold: preservation and access. The NCTE wanted the recordings preserved for posterity — but a primary intent was also to distribute them for pedagogical purposes and to allow access to the recordings, the same ethos the PennSound project is built upon.

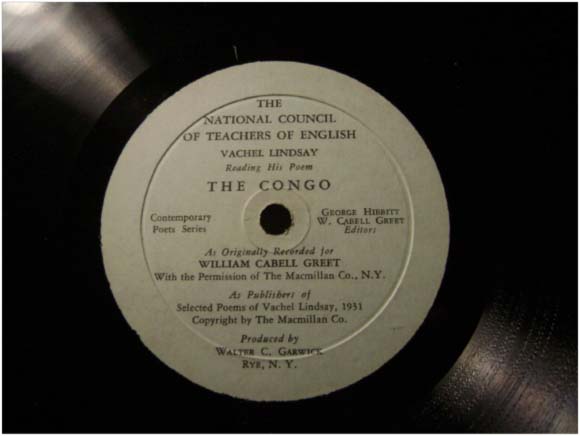

Hatfield then moves on to the main purpose of this letter, which is to inform Williams that distribution of the record, and thus his royalty payments, will be delayed due to a change in distributor. Here we learn that the NCTE will distribute the record through Walter C. (Cleveland) Garwick of Rye, New York. This turns out to be a highly significant fact, as it links the Williams recording to a series of poetry recordings edited by Greet and Hibbitt and produced by Garwick, the Contemporary Poets Series.

W. Cabell Greet and the Contemporary Poets Series

Eleven years before Greet would record Williams, an event occurred that would serve as the inspiration to create the Contemporary Poets Series. In January 1931, Vachel Lindsay approached Greet and asked him to record his work. Lindsay believed that poetry exists as a sounded entity before it is later written down, a belief that seems to be shared by Greet. In fact, one report claims that the earliest addition of a record Lindsay and Greet would make together contained the text, “During his life-time Vachel Lindsay was properly disdainful of printed poetry except as a libretto to be followed while hearing sounded poetry.” Given his views on the precedence of poetry’s sonic properties over its textual manifestation, Lindsay felt a sense of urgency[5] to use the technology of the time to capture and preserve the sound of his poetry in records. Lindsay approached several commercial record labels before coming to Greet and was rebuffed by each. Greet had in his possession an Amplion disc (record) maker,[6] which he used to make recordings of American speech and dialects of the time. The device could cut records from aluminum platters and was not the highest quality, even by standards of the time. Nonetheless, Greet and Lindsay worked together, sponsored by the Columbia University Library and Columbia University Council for Research in the Humanities, to record thirty-eight records, three hours in total, comprising nearly all of Lindsay’s poetry. Lindsay would die less than one year later. These recordings would later be released as part of the Contemporary Poets Series, but the interaction between Greet and Lindsay is the most critical aspect to note. Lindsay’s views on poems as sounded entities influenced the entire ethos of the Contemporary Poets Series: the series came to be characterized by a phonotextual emphasis — that poems are best studied with recordings alongside their respective texts. As such, the series lays the groundwork for the field that would become phonotextuality by considering the interplay between the sonic and textual properties of a poem.

Around 1934, Greet and Hibbitt partnered with the National Council of Teachers of English, an organization devoted to “improving the teaching and learning of English and the language arts at all levels of education,” to establish the Contemporary Poets Series. Greet’s founding of the Contemporary Poets Series made the NCTE a logical partner. Greet framed his announcement of the creation of the series with this sentiment: “The lack of phonograph records of men of letters has been a source of regret to many teachers, students, and other lovers of literature.” The group had national reach and the resources to help Greet distribute the records. Indeed, Greet’s stated intention, paired with Hatfield’s later letter to Williams in which Hatfield looks forward to the distribution of the Williams recordings to schools, demonstrate that the series was founded for pedagogical purposes. It would continue to function as such for at least a decade.

Around 1934, Greet and Hibbitt partnered with the National Council of Teachers of English, an organization devoted to “improving the teaching and learning of English and the language arts at all levels of education,” to establish the Contemporary Poets Series. Greet’s founding of the Contemporary Poets Series made the NCTE a logical partner. Greet framed his announcement of the creation of the series with this sentiment: “The lack of phonograph records of men of letters has been a source of regret to many teachers, students, and other lovers of literature.” The group had national reach and the resources to help Greet distribute the records. Indeed, Greet’s stated intention, paired with Hatfield’s later letter to Williams in which Hatfield looks forward to the distribution of the Williams recordings to schools, demonstrate that the series was founded for pedagogical purposes. It would continue to function as such for at least a decade.

The Contemporary Poets Series was housed at Greet and Hibbitt’s Columbia lab into the 1940s, the first release in the series being a subset of the Vachel Lindsay recordings. Greet published calls for suggestions of poets to include in the series in scholarly journals of the time, including American Speech (a cosponsor of the series),[7] The Quarterly Journal of Speech,[8]and The Elementary English Review,[9] published by NCTE. The series would come to include a wide range of poets, specifically Lindsay, Williams, Gertude Stein, W. H. Auden, Archibald MacLeish, T. S. Eliot, Robert Frost, Robert P. Tristram Coffin, E. E. Cummings, Mark Van Doren, John Peale Bishop, Leonie Adams, Marianne Moore, Stephen Vincent Benet, William Rose Benet, Conrad Aiken, Aldous Huxley, John Gould Fletcher, Alfred Kreymborg, Carl Sandburg, and Allen Tate.[10]

Addressing teachers in his solicitations, Greet asks questions like: “What [do] poems lose most by being printed?”[11] and “What poems would be most useful in emphasizing for students that all poetry, not only the so-called lyric, exists first as song, in aural terms, before it is reduced to print?”[12] The assumption Greet makes here is that the transference of a poem from a kinetic, sounded entity to a textual manifestation is a reductive, privative process. In this he echoes Pound and foreshadows Olson in thinking of poetry written in vers libre as being as musical or more so than lyric.

Walter C. Garwick

The Walter C. Garwick mentioned in Hatfield’s note to Williams is a significant figure of the time: he worked as a producer and audio consultant for many of Greet’s recordings, and also manufactured and sold one of the first portable recording devices, a machine he sold to John A. Lomax for use in creating field recordings. While Greet had originally secured Erpi Picture Consultants Inc., a producer of educational films, to handle the production of the series, he eventually came to work with Garwick as his engineer and, later, his producer/distributor. In the November 1941 agenda of the NCTE Board of Directors meeting, Greet refers to Garwick as the NCTE’s “technical expert”[13] vis-à-vis recording poets. The title here is likely intended to cover the wide range of Garwick’s work on the project, from operating the recording equipment through handling distribution of the records. During the time of the early recordings, Garwick worked for Fairchild, a company that built audio-recording equipment and sold a competitor to the Amplion record maker used by Greet and Hibbitt. He also seems to have served as a recording engineer at Columbia, where he worked with Greet making recordings. This is perhaps where they initially met.

In 1933, in correspondence with the famous American folklorist and ethnographer John A. Lomax, Garwick writes that he is leaving Fairchild and starting a company that would manufacture a record maker that would be the lightest/most portable of its time at under a hundred pounds (the Fairchild model weighed about 300 pounds). The device could cut aluminum and celluloid records and would be battery powered, marking it a significant technological innovation. Some of the other field recording devices of the time required being hitched to a truck to be moved and were powered by removing the wheel of the truck and running a drive belt from the axle to the recorder. In correspondence with Lomax, Garwick works to sell him the device, which the Library of Congress would eventually purchase for Lomax, for about $500, or around $8,500 in today’s dollars, and Garwick notes his affiliation with Greet. Garwick’s mention of his relationship with Greet likely refers to their working together to record Lindsay two years earlier, along with their pursuit of recording American dialects and speech. In fact, Hatfield suggests in his letter to Williams that Garwick was the engineer who recorded Williams. It is unclear what device Greet was using in 1942 when Williams came in to be recorded, but it seems likely that it was the same Amplion used to record Lindsay.

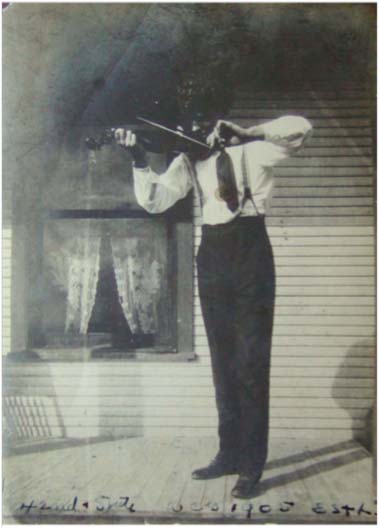

In researching Garwick, I had the pleasure of interviewing his great-granddaughter Christine Whittaker, who helped develop a fuller picture of Garwick than I was able to find anywhere else, both through her familial knowledge of her great-grandfather and from research she conducted on him in the Lomax archive at the Library of Congress. She spoke with pride of Garwick’s breadth of accomplishments, especially given his modest background and eighth-grade education. He went on to work as an audio engineer for Fairchild and as a recording engineer for Columbia, where he created the lightest field-recording device of his day and sold it as part of his own company. He traveled the country (over 30,000 miles, he notes to Lomax in a letter) recording samples of Americana in the field — a pursuit that William Carlos Williams would have lauded, given his interest in the American idiom. While there appears to be no extant model of Garwick’s field-recording device, his family is proud that his legacy lives on through his recordings and preserved correspondence with Lomax at the Library of Congress. Christine was kind enough to provide me with this picture of Walter C. Garwick playing his father’s violin, taken in 1905 (see above; image used courtesy of Christine Whittaker and family).

In researching Garwick, I had the pleasure of interviewing his great-granddaughter Christine Whittaker, who helped develop a fuller picture of Garwick than I was able to find anywhere else, both through her familial knowledge of her great-grandfather and from research she conducted on him in the Lomax archive at the Library of Congress. She spoke with pride of Garwick’s breadth of accomplishments, especially given his modest background and eighth-grade education. He went on to work as an audio engineer for Fairchild and as a recording engineer for Columbia, where he created the lightest field-recording device of his day and sold it as part of his own company. He traveled the country (over 30,000 miles, he notes to Lomax in a letter) recording samples of Americana in the field — a pursuit that William Carlos Williams would have lauded, given his interest in the American idiom. While there appears to be no extant model of Garwick’s field-recording device, his family is proud that his legacy lives on through his recordings and preserved correspondence with Lomax at the Library of Congress. Christine was kind enough to provide me with this picture of Walter C. Garwick playing his father’s violin, taken in 1905 (see above; image used courtesy of Christine Whittaker and family).

Garwick’s involvement with the Contemporary Poets Series is significant because he serves to create a relation between early sound recordings as ethnographic research, specifically Lomax’s field recordings and Greet’s recordings of American dialects, and as a lens to better elucidate poetry. By juxtaposing ethnography with poetry, Garwick’s involvement demonstrates poetry as a living, social, corporeal entity, as perpetually representative of the American zeitgeist. Just as Lomax pursued the recording of cowboy songs and African American spirituals because they would be reduced by representation on the printed page alone, so too did Greet apply this ethos to poetry, where he served as a pioneer of phonotextual studies.

Significance of The Contemporary Poets Series

The NCTE’s Contemporary Poets Series marks the first known attempt to create a collection of recorded poetry for pedagogical purposes. In doing so, it represents a kind of proto-PennSound. The underlying belief that teachers and students would change their understanding of poems by hearing them as sounded structures foreshadows a key impetus for Al Filreis and Charles Bernstein’s founding PennSound about seventy years later. In a PennSound podcast about the project’s founding, Al Filreis asserts that pedagogical interests were central to his and Bernstein’s decision to create PennSound. We hear in Filreis’s remarks echoes of W. Cabell Greet, in the early 1930s, explaining the intentions of the Contemporary Poets Series. For example, when Greet solicits recommendations for poets to record as part of the series, he frames the call for ideas with this question: “What poems would be most useful in emphasizing for students that all poetry, not only the so-called lyric, exists first as song, in aural terms, before it is reduced to print?” While the premise that all poetry exists first as song can be debated, the underlying sentiment that sound can help to establish a connection between student and poem is at the heart of the series’ pedagogical ethos. In addition, Greet’s statement sets forth the idea that a poem exists in multiplicity: as a sounded structure in addition to a textual construct. Leaving aside whether the textual representation of a poem is reductive, the intent of illustrating for students that poetry does indeed also exist off the printed page, as an aural, performative entity, is a principle shared between the Contemporary Poets Series and PennSound.

Another similarity between the projects is the creation of two different subseries of poetry: contemporary and historical. Just as PennSound contains a ‘classics’ section, featuring readings of classic poetry (Swift, Pope, Dryden, etc.) by scholars of the works, Greet created a Historical Poets Series alongside the Contemporary Poets Series. At the same time that he issues a call for recommendations for contemporary poets to record, Greet also asks: “What works of and other past poets writers would it be well to have recorded by present-day scholars as a help in studying and teaching literature? Such as, for example, poems of Burns, Chaucer, and Shakespeare.”[14] (The PennSound Classics archive in fact contains readings of both Chaucer and Shakespeare.)

In addition to its pedagogical resonance with PennSound, the Contemporary Poets Series stands as an important moment in the development of ethnographic approaches to the American poetry archive: the series was recorded by an ethnographer whose primary scholarship centered on the American dialect. The twofold use of the machine for recording samples of the American dialect and for recording poets should not be viewed as happenstance. The two projects complement each other and demonstrate that poetry is a living entity, woven into the cultural fabric of a society. Just as language and its changes reflect social relations and temporal shifts, so too does the poetry of the time. Greet’s inclusion of poetry in his recording agenda affirms this fact and reframes how we approach these recordings. Understanding the historical context of their creation and situating their intent between pedagogy and ethnography, both presentational and representational, allows for new close listenings of the Williams recording and others in the series. For example, the Williams recordings framed as ethnography, specifically lexicology, foreground Williams’s belief that the American idiom is the foundation upon which American poetry, and indeed American life, is built. When we hear Williams read “To Elsie” in this context, the poem becomes a negotiation of a new America based on who gets to contribute toward the evolution of the American idiom.

Through its pedagogical intent and phonotextual emphasis, the Contemporary Poets Series prefigures PennSound. But the projects share a greater relation: several of the recordings made by Greet have found their way into PennSound. In addition to the Williams recording, PennSound offers some of the recordings of Vachel Lindsay that inspired the creation of The Contemporary Poets Series; we are also researching whether the Gertrude Stein recordings in PennSound were those of Stein made by Greet, and we are searching for other recordings from the series. Our intent is to create a PennSound page dedicated to the Contemporary Poets Series, which we hope will further contextualize recordings as we bring them together in digital form for the first time.

The correspondence between Williams and the NCTE reveals a hope the series founders had that recordings of Williams and others would lead to preservation and access. The fact that these recordings are making their way to PennSound, which has the technological advantage of being able to accomplish both of these goals on a much larger scale, affirms and extends Greet’s vision. “Teachers and students and lovers of literature” anywhere in the world can now hear Williams and Lindsay reading their work from Greet and Hibbit’s Columbia recording studio and consider the poems as sounded structures, and as a technological bridge between kindred projects.

The author would like to thank everyone who provided insight, counsel, and assistance with this essay, especially Steve Green, Christine Whittaker, Todd Harvey, Mary Ellen Budney, Julia Bloch, and Al Filreis

1. Cabell Greet, “Records of Poets,” American Speech 9, no. 4 (December 1934): 312–13. Hereafter cited as RoP.

2. Columbia University to Williams, 19 April 1940, box 4, container 132, William Carlos Williams General Correspondence, Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

3. National Council of Teachers of English to Williams, 14 November 1942, box 16, container 495, William Carlos Williams General Correspondence, Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

5. This sense of urgency is suggested by Greet’s claims that Lindsay points out a “need for action” (RoP) vis-à-vis beginning to record poets reading their work, and also that Lindsay “insisting upon the importance of his own reading of his poetry, searched in vain for a commercial company to make the records.”

6. John A. Lomax, in a letter to the chief of music for the Library of Congress, notes that Greet uses the Amplion recorder. Lomax is, at the time, getting price quotes for a field recorder of his own. The possible options are the Amplion model and the Fairchild Co. model. Lomax to C. Engel, May 2, 1933, Lomax Correspondence, Library of Congress.

8. Cabell Greet, “The Lindsay Records,” The Elementary English Review 9.5 (May 1932): 122, 128. Hereafter cited as LR.

9. Cabell Greet, “Records of Poets,” Quarterly Journal of Speech 21.2 (1935): 296–96. Hereafter cited as QJS-RoP.

10. A partial listing of records is listed in WorldCat. Others are noted in The Letters of Gertrude Stein and Carl Van Vechten, ed. Edward Burns(New York: Columbia University Press, 1986), 422n2.

13. NCTE Board of Directors meeting agenda, 20 November 1941, record series 15/70/2, box 1, University of Illinois Archives.