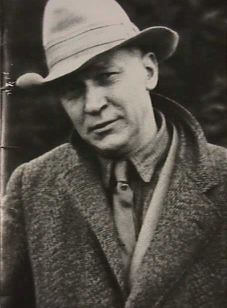

Vachel Lindsay, 'The Congo'

LISTEN TO THE SHOW

Many of us read Vachel Lindsay in school — at least until he was removed from the anthologies. Few of us have heard the recordings of Lindsay performing — not just reading, but truly performing — his poems, “The Congo” most (in)famously. So we PoemTalkers decided to try our hand at the first section of Lindsay’s most well-known poem. Al suggests that readers and listeners must attempt to “get past” the obvious racism (even of the opening lines), but Aldon Nielsen takes exception to that formulation, and off we go, exploring the problem and possibilities of this poet’s foray — Afrophilic but nonetheless stereotype-burdened — into African sound and, more generally, the performativity of a culture.

Many of us read Vachel Lindsay in school — at least until he was removed from the anthologies. Few of us have heard the recordings of Lindsay performing — not just reading, but truly performing — his poems, “The Congo” most (in)famously. So we PoemTalkers decided to try our hand at the first section of Lindsay’s most well-known poem. Al suggests that readers and listeners must attempt to “get past” the obvious racism (even of the opening lines), but Aldon Nielsen takes exception to that formulation, and off we go, exploring the problem and possibilities of this poet’s foray — Afrophilic but nonetheless stereotype-burdened — into African sound and, more generally, the performativity of a culture.

Charles Bernstein finds this “one of the most interesting poems to teach,” and adds: “[Lindsay] felt there was something deeply wrong with white culture, that it was hung up, ... that it was disembodied, that it was too abstract.” All the problems of the poem, Charles notes, remain present when one reads or hears it. It’s all there. It’s not a “bad example” of something; it makes its own way (or loses its way) in the modern poetic tradition, as it is.

What can Lindsay teach us today? Michelle Taransky is sure that young writers can learn from Lindsay’s experiments, and not just in sound — but also in the way he uses marginal directions, which serve as performance (or production) cues. She commends Lindsay for making available to us the realization “that a poem doesn't have to be read in a monotone way…and that they [young poets today] can read a poem in a way that seems appropriate to them at that time.”

What can Lindsay teach us today? Michelle Taransky is sure that young writers can learn from Lindsay’s experiments, and not just in sound — but also in the way he uses marginal directions, which serve as performance (or production) cues. She commends Lindsay for making available to us the realization “that a poem doesn't have to be read in a monotone way…and that they [young poets today] can read a poem in a way that seems appropriate to them at that time.”

Aldon doesn't want to “get past” the tension between Lindsay’s desire to make a progressive statement and the racist content in the poem; as a whole, this work creates a tension that “absolutely at the core of American culture.” Aldon is hesitant to use the phrase “teachable moment” (which during 2009 has been a phrase that is dulled from facile overuse in “ongoing conversation” about race) but that —teachability — is about the sum of it: to teach this poem is to gain access to a central American discussion.

November 30, 2009

American poetry and political defeat

by Michael Ruby

IN THE first election year that mattered to me, 1968, Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy were assassinated, my country killed hundreds of thousands of people in Southeast Asia, and Richard Nixon was elected president. In the decades that followed, I have always been unhappy with the leadership and direction of this country, usually very unhappy.

Michael Ruby

I was born a believer in peace. I say fight for the right.

Be a martyr and live. Be a coward and die.

— Susan B. Anthony speaking

in Gertrude Stein’s

“The Mother of Us All”