Poetic representations of the holocaust

Poetic engagements with the Holocaust must overcome the argument that language cannot portray the inhumanity of the Nazis’ actions. Poetry must challenge its traditionally humanist pose in order to respond to the dehumanizing Shoah. Poetry can either concentrate on the highly personal — which runs the risk of reducing the scale of the events — touching the reader with the retelling of individual testimony, or it can try and reform language to find a new means of expressing the inexpressible.

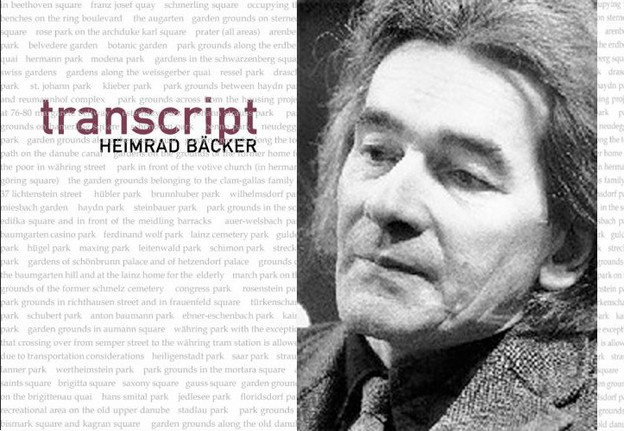

Heimrad Bäcker (1925–2003) renounced his former membership of the Hitler Youth and the Nazi Party after World War II. He spent the remainder of his life as a poet, editor, and intellectual as a means of confronting his own involvement in how the Nazis used language itself as a means of propagating the Holocaust. Bäcker was a member of the Hitler Youth’s Press and Photography Office before he worked as editor of the Austrian avant-garde press Neue Texte. His Hitler Youth employment exposed him to the anaesthetized prose of the Nazi’s intricate documentation of their Final Solution.

Theodor Adorno’s dictum that all poetry after Auschwitz is immoral embodies the crisis of poetics following the Holocaust. How is European poetry to situate itself? In the Holocaust much literature was as defiled as the authors who had written it; poetry and prose were brought to unwitting service of a culture’s destruction. With Nachschrift (1986) Bäcker poetically argues that the best way to engage with the language of the Holocaust is to present it baldly, without editorializing and without personal intercession. Nachschrift is finally available in English translation as transcript (Dalkey Archive, 2010, translated by Patrick Greaney and Vincent Kling).

transcript is a collection of page after mostly empty page, interrupted by brief, aphoristic (strictly documented) quotations from internal Nazi memoranda, private letters and reports presented in the banal, toneless language of bureaucracy. Bäcker referred to his style as dokumentarische dichtung (documentary poetry) and where he revised the original text, every detail is acknowledged in eerie echo of the precision of the source authors.

Bäcker created transcript without knowledge of Charles Reznikoff’s Holocaust (1975). Reznikoff used a similar compositional strategy but drew from survival testimony at the Eichmann and Nuremberg trials. Both books are bereft of traditionally poetic language. Reznikoff ’s, however, mines testimony for the stuff of poetry — prosaic sentences with poetic line breaks that testify to traumatic experience. Bäcker rejects the testimony in favor of the corporate, but transcript is as emotionally engaging as any humanist confession. The vast majority of transcript could be excerpted from any obsessively documented corporation pleading for increased shipments where “the times on the train schedule correspond to the hours of the day 0-24” (28) when “it is very difficult at the moment to keep the liquidation figure at the level maintained up to now” (52).

As a forerunner of contemporary conceptual poetry, transcript displays how potent and emotional the corporate can be — and how language simultaneously veil and unveils. Bäcker’s involvement in the Nazi party is implicitly the subject of transcript. His sentence is the Sisyphean task of sifting and resifting banal primary documentation in search of the poetic in the unspeakable.